The origins of British rule in India lie with the East India Company, a British trading company that operated from the 17th to the 19th centuries. The EIC received a Royal Charter in 1600, from Elizabeth I, was owned by wealthy often mercantile or aristocratic shareholders, and was not dissolved until 1874. Although it was originally founded to trade with the East Indies, its domain expanded to include the Indian subcontinent and areas of China.

The influence of the EIC is hard to overestimate. At the height of its power, after establishing its dominance over Dutch, Portuguese and French trading companies, it could account for half of the world’s trade, and this was in much-needed basics such as tea, salt, pepper and materials including cotton, dyes and saltpetre (used for gunpowder) – plus opium. Luxury goods such as silks were also traded.

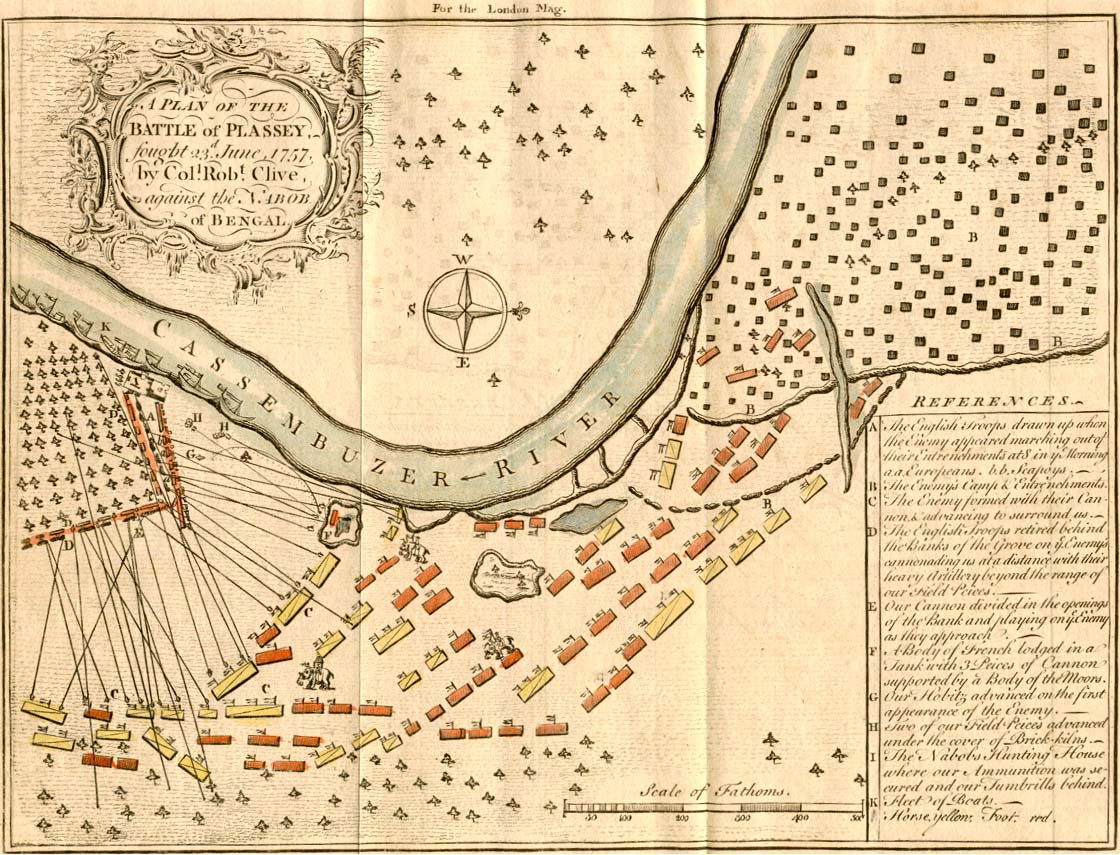

The company’s exponential growth and its incorporation of private armies meant that it came to rule areas of India. Military rule took a firmer hold after the Battle of Plassey of 1757, which saw the EIC defeat Bengali and French opposition to its rule in a campaign led by Robert Clive, ‘Clive of India’. The main player in bringing India under the British crown, Clive’s reforms marked a new development in the history of the East India Company and its move to become government as well as a trader. Numerous EIC records, reflecting both of these roles, can be found online at www.TheGenealogist.co.uk.

From this time British presence in India grew quickly, and British administration of the Indian subcontinent centred around three ‘presidencies’: Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. By 1800 the British controlled around a half to two-thirds of India.

Before 1857 the main aims of British company rule in India were reform and improvement – in other words, Anglicisation of the Indian people. In reality, most of the company’s money was spent on its armies and on defence rather than on education or economic development. Although British rule was more evident in the larger cities and towns of India, especially trade centres, those in the countryside were taxed in order to be controlled. Indian dissatisfaction, especially among dispossessed landowners, grew. The influx of Christian missionaries was also unwelcome and sometimes feared by many in Muslim and Hindu society.

British control in some areas of India was often shaky, but when, in 1857, sepoys (soldiers from northern Indian armies who kept order for the British) rebelled over army modernisation efforts and the rumoured use of pig and cow fat (forbidden in Islam and Hinduism) for lubrication of new rifles, rebellion took hold. Without their Indian colleagues’ cooperation, the British rulers could not keep control, and once the rebels were subdued the British Raj took control of India.

Under British governmental rule, Indian society underwent rapid change. The Indian railway grew to be the fourth largest in the world, with almost 30,000 miles of track set down by the 20th century. Canals were built, which improved irrigation and trading links. Famines that had decimated areas of India in previous decades became less of a threat as prosperity increased, and educational reforms improved many lives. A number of relationships between British men and Indian women are also attested to by wills. These show that in the 1780s a third of British men there left their possessions to Indian wives and children. The 1800s witnessed Europeans adopting local dress, learn Indian languages and adopt Indian ways of life and entertainments. However, such cultural mixing and relationships seem to have been less common in the Victorian era.

Intriguing article?

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

If you have ancestors with connections to British India there are a number of resources at TheGenealogist that will be of help, including The East India Company Register and Directory for 1805, 1820 and 1834. As well as those who held political and military offices, the directories list company agents, medics and surgeons, Public Works Department employees, educators and civil servants. So, if you have an ancestor with British Indian connections, it is well worth a search. Also at TheGenealogist, the 1865 Indian Army and Civil Service List details particulars of Indian Army (the successor to the East India Company armies) army officers and those who worked for government offices in India.