The Salvation Army was founded by Methodist lay preacher William Booth and his wife, Catherine, in response to the poverty and homelessness they encountered in the East End of London. Its mission was to bring spiritual and practical help to those in desperate need, with an emphasis on breaking the cycle of dependency, getting people back on their feet and restoring some dignity to their lives.

Today the Salvation Army is active in more than 100 countries, bringing relief in the wake of emergencies and natural disasters, as well as caring for the elderly, the lonely, the destitute, victims of domestic abuse and those with addiction or mental health issues.

Another strand to the Salvation Army’s mission is its Family Tracing Service, which was established in 1885 as Mrs Booth’s Enquiry Bureau, and has reunited many long-lost or estranged family members.

Spreading the word

William Booth converted to Methodism in 1844, aged 15, while apprenticed to a pawnbroker, and in 1851 joined the Methodist Reform Church. But after disagreements with the church he took to the streets as an independent evangelist, spreading the message of salvation to the poor.

In June 1865, Booth was preaching outside the Blind Beggar public house in Whitechapel, and so impressed a group of street preachers that they asked him to lead their mission at a nearby Quaker burial ground. The first meeting on 2 July led to the formation of the Christian Mission. Subsequent meetings took place in the streets, often outside public houses, as well as in a number of buildings on or near Whitechapel Road, including a dance academy and a skittle alley.

In 1867 the Mission acquired its first headquarters at 220 Whitechapel Road, moving three years later to the People’s Mission Hall, which was not only used for worship but also housed a soup kitchen.

With a change of name to the Salvation Army in May 1878 came a new, quasi-military structure. A uniform was introduced, along with an increasing use of military terminology. The clergy became known as officers, those training to become officers were ‘cadets’ and ordinary members were ‘soldiers’, while individual chapels were known as ‘corps’. Asked about the new name, Booth responded: What does it mean? Just what it says – a number of people joined together after the fashion of an army; an army for the purpose of carrying Salvation through the land, neither more nor less than that.

Music was also seen as an important way of reaching out to people and helping to spread the Christian message, with Booth declaring: We want a body of red-hot people to sing the songs of salvation. The world has not yet seen what might be done by the singing of a people whose hearts were full of the spirit of God.

Songs were often penned by Salvationists and set to well-known secular tunes that were instantly recognisable and helped to capture people’s attention. Musical instruments were soon added to the mix, and from 1889 to 1972 the Salvation Army had its own musical instrument factory.

Music remains at the heart of Salvation Army life: choirs and bands are still an integral part of worship, and there are frequent events, training courses and workshops to encourage creativity and spiritual development among its members.

Social work

In 1884, The Salvation Army’s first women’s refuge was opened in Whitechapel to offer shelter, food and clothing to young girls rescued from brothels. By 1890 there were 13 such homes, which taught the girls a range of skills from bookbinding to needlework and knitting. A hospital for unmarried mothers opened at Ivy House, Hackney, in 1888, and again this offered sanctuary as well as training the women for employment – usually domestic service – while helping them to place their babies with nurse-mothers. In some cases the mothers were able to keep their babies, but most of the babies went on from their nurse-mothers into adoption. In 1913 a Mothers’ Hospital and training school for nurses and midwives opened in Clapton; this became part of the NHS in 1948 and was operational until 1986.

The first men’s hostel was established in Limehouse in 1888, selling bread and soup for a farthing, as well as training men in a number of trades and helping them into employment. The number of such hostels quickly grew, and were known as ‘elevators’. In 1891, the Salvation Army acquired a working farm at Hadleigh in Essex, where men and boys were offered accommodation and training. More than 60% went on to find employment.

Booth also established his own match-making factory in Old Ford, East London, using non-toxic red phosphorous, after discovering that other factories exposed their workers to deadly levels of white phosphorous. The factory was soon out-performing its competitors.

During both world wars the Salvation Army offered support for the troops, including working in field hospitals and canteens, and holding concerts at Prisoner of War camps. Today Booth‘s legacy continues in the form of humanitarian aid all over the world.

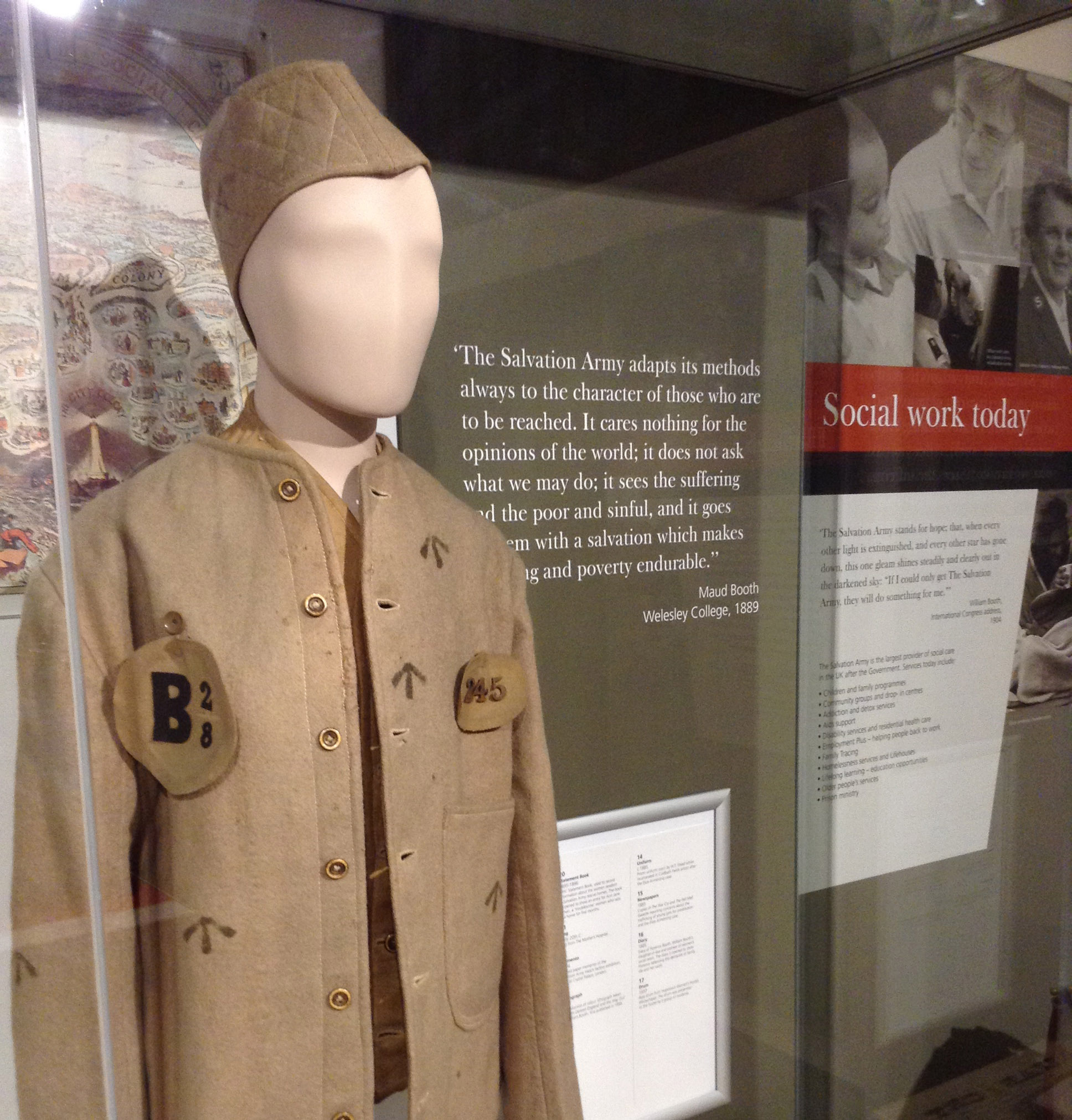

A display cabinet at the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre in south London

Salvation Army records

The best starting point for any research into Salvation Army ancestry is the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre at Denmark Hill, London (www.salvationarmy.org.uk/

international-heritage-centre), which includes a museum, library and archive. The museum offers a fascinating insight into the Salvation Army story, while the library includes books by and about the Salvation Army as well as complete runs of all Salvation Army periodicals.

Intriguing article?

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

There are two distinct sets of records for researching Salvation Army ancestors; those relating to people who served with the Salvation Army and those relating to people who were helped by the Salvation Army.

Unfortunately substantial numbers of records were lost when bombs destroyed The Salvation Army’s International Headquarters in 1941, but plenty survived, so there is a good chance of being able to trace your ancestors here.

For officers, the most useful records will be their career cards, which include details of all appointments held, with dates. In the case of married officers, both are recorded on the husband’s card, together with details of any children. Some also have photographs attached. If an officer retired before 1941, the career card is unlikely to have survived, but those who continued their service beyond 1941 will have had their career card reconstructed from other sources. All career cards are very detailed, so likely to be a good source of information for family historians.

Part of a baby’s extensive record at the Ivy House hospital for unmarried mothers

The centre also holds a complete set of records for officers trained in the UK from 1905-2000 for men and 1914-2000 for women. These give the full name, date of birth, corps serving at before entering training, previous occupation, languages spoken, other skills and details of first officer appointment.

After completing their training some cadets were appointed sergeants, and they stayed at the college to help train the next intake of cadets. The centre holds a list of sergeants from 1899 to 1947.

Other possible sources of information for officers include personal papers periodicals. The Salvation Army Year Books are particularly useful, as they include ‘Who’s Who’ lists for officers on active service, details of retired officers, and lists of ‘Promotions to Glory’, the term used by the Salvation Army for the death of one of its members. The ‘Promotions to Glory’ registers include birth and death dates, address, rank, length of service and place of burial.

Records for soldiers are more limited. The centre holds some soldiers’ rolls for closed corps, but most are held by individual corps. To trace a soldier ancestor, you need to know the name of the corps he or she served at, so that the centre can check whether they hold any relevant records. If not, you would need to approach the corps direct.

If you are lucky enough to find your ancestor in one of the soldiers’ rolls, they are very detailed, giving name, roll book number, address, marital status, date of enrolment and where the soldier had come from.

Records for men and women helped by the Salvation Army are also held at the centre, and for women these are quite substantial. Statement books for rescue, maternity or inebriates’ homes from 1886 to 1996 give lots of detailed information. Records typically include the woman’s name and age, dates of arrival and departure, previous location, who referred her and her destination on leaving the home.

When a baby was born in the maternity home, a separate baby sheet was attached, giving the names of the mother and child, date and place of birth, address of registrar, and the name and address of father, if known.

Running in parallel with the statement book for London is an interview book, which contains notes made at pre-admission interviews. These were in free format, so the details are not consistent across all records, but they can offer more information than a statement, such as clarifying the relationship between the applicant and the referrer, why the woman was referred to the home and what sort of work she had been doing. In most cases, this would be domestic service.

All records relating to individuals are closed for 75 years, or in some cases 100 years.

Other useful sources of information include the London Metropolitan Archives and St Bartholomew’s Hospital, both of which hold administrative records for The Mother’s Hospital.

In the print edition

Read more about the temperance movement, and non-Christian faiths in Britain, in Issue 4 of Discover Your Ancestors, available online at discoveryourancestors.co.uk