In March 1837, an amiable, elderly gentleman crept into court to defend a breach of promise claim. His name was Samuel Pickwick and, soon, the case of Bardell v Pickwick was a cause célèbre. For the next hundred years, the names of the plaintiff and defendant, the solicitors Dodson and Fogg, the barrister Sergeant Buzzfuzz and Pickwick’s servant Sam Weller, were woven into the cultural fabric of Britain.

All these characters sprang from the imagination of Charles Dickens, the radical author and campaigner who was at the start of a glittering career as a novelist. The Pickwick Papers, his first full length work, was published in monthly instalments between March 1836 and November 1837 as a succession of incidents involving the same four hapless comrades. It was the perfect way for an ambitious writer to demonstrate his talent for plotting, characterisation and satire, as Mr Pickwick and his three companions stumbled from one misadventure to another.

As a young man, Dickens had worked briefly in a solicitors’ office before opting to earn his living as a journalist. At first he could not escape from the law as he was an obvious choice to sit in court and take notes of the varied trials which came before judge and jury. This reinforced his already low opinion of the English legal system and its practitioners, who, he considered, were more motivated by their own interests rather than the pursuit of justice. That Dickens used his first major writing commission to showcase this canker reveals just how much they disgusted him.

In The Pickwick Papers,Dickens chose the popular claim of breach of promise to marry to show up the vices of solicitors and barristers, while also poking fun at the judiciary. Breach of promise enabled a person who had been jilted to claim damages from their former intended. Most cases were brought by women. Impoverished spinsters and widows were not well regarded by society and had few options for earning their living. Winning damages was a way of getting some capital of their own. It was also a canny business move by the author. Breach of promise cases were popular with readers, because they often involved saucy or embarrassing revelations. Samuel Pickwick had already gathered an appreciative audience and his latest dilemma could be expected to attract a wide readership.

The number of claims was increasing in the 1830s, because lawyers had discovered that breach cases were easy to win, even when the alleged offer of marriage was jocular, or the woman’s evidence was questionable. Shady solicitors actively sought out women who had been unlucky in love, offering the first ever ‘no win, no fee’ deals to entice them to pursue errant fiancés for all they could get. Damages of several hundred pounds were dangled as an inducement to wash dirty linen in public, because if a woman was only awarded one shilling, the defendant would be ordered to pay her legal costs, netting an income for the lawyer.

Samuel Pickwick’s woes began when he asked his widowed landlady, Martha Bardell, whether she thought that two could live as cheaply as one. It was an unusual way for a tenant to tell his landlady that he was about to employ a manservant but, by no stretch of the imagination, was it an offer of marriage. However, Mrs Bardell interpreted the conversation as a proposal, flung her arms round her lodger’s neck and promptly fainted. Pickwick held her waist to stop her falling to the floor, just as his three companions arrived and observed an apparent embrace. Unaware that Mrs Bardell now thought that she was about to be married, Pickwick engaged his new manservant, Sam Weller, but made no attempt to organise a wedding.

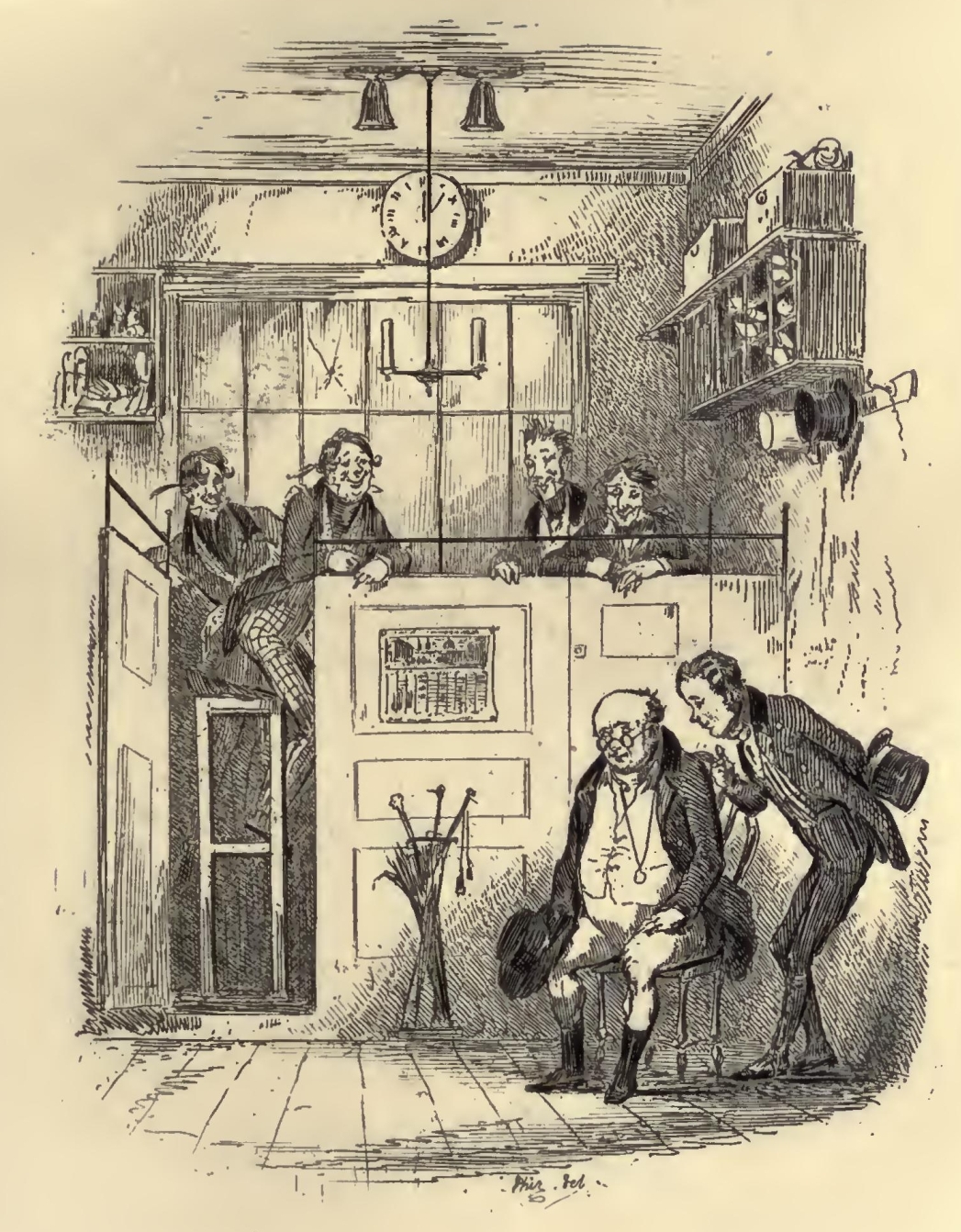

Some weeks later, rather than asking her fiancé when they would wed, Mrs Bardell consulted a firm of solicitors about her matrimonial prospects. Messrs Dodson and Fogg were devious and disreputable. They confirmed that she was indeed a jilted woman. From this point, Dickens portrayed, in comic terms, corrupt solicitors who indulged in legalised blackmail and intimidation, a bullying, bombastic, barrister, Sergeant Buzzfuzz, who twisted words to a meaning they did not have and an incompetent judge who slept for part of the trial. Little wonder that the jury decided Martha Bardell was a wronged woman and awarded her £750 to compensate her for not becoming Pickwick’s wife. The only saving grace was the evidence of Sam Weller, who mentioned that Dodson and Fogg had taken Mrs Bardell’s case ‘on spec’ knowing that Pickwick would be told to pay their inflated charges. Weller’s words prevented the jury awarding £1,500 in damages.

From the outset, the impact of Bardell v Pickwick was extraordinary. Dickens declared in his next novel, Oliver Twist, that “the law is an ass”, perhaps not realising that he had made an ass of the law by establishing inferred proposals as part of the English legal system. Although standards were low in breach cases by the 1830s, Bardell v Pickwick appears to be the first time a claim succeeded without an unambiguous proposal being made. It was not the last. In 1840, a Barnstaple vicar was sued shortly after his wedding. Henry Luxmore and Elizabeth Irwin had been friends for many years, but the letters which she produced to prove their engagement had no reference to marriage. Rather than ruling that she had no case, the judge told the jury to decide whether they felt able to infer Luxmore’s intention to marry Elizabeth. Probably aware of Bardell v Pickwick, the jurors decided that they could and awarded the fortunate spinster £400 damages.

Three years later, Amelia Rooke successfully sued her elderly cousin Thomas Conway, admitting that he had not proposed, but his conduct had led her to believe that he would. Conway stated that any attention he paid Amelia was mere courtesy towards a young relative, but she won the case. After this, an inferred proposal remained a hazard of courtship until 1869 when the law was changed to ensure that a definite offer had been made.

Intriguing article?

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

The trial scene clearly resonated with legal professionals and allusions to Pickwick characters were regularly made in civil court cases for decades. It became a jocular code for imputing dubious motives to the other side, without directly accusing them of poor conduct. Likening the other party’s solicitors to Dodson and Fogg implied that their reasons for pursuing the case were mercenary, and hence that the case was a weak one. Comparing a barrister to Sergeant Buzzfuzz hinted that he was bending the facts. Mrs Bardell became the personification of a scheming widow, while Sam Weller denoted a truthful, reliable witness and Samuel Pickwick an honest but maligned defendant. It was all part of a theatrical performance which was played out to influence the jurors and indicates that the middle-class men who made up the jury remained well-versed in Dickens.

Charles Dickens himself was another reason why Bardell v Pickwick stayed in the public’s mind. Until his death in 1870 he regularly made personal appearances to read from his works. The trial, with its range of characters, long, bombastic speeches and unfair outcome was particularly effective for creating emotional engagement with the audience.

In 1875, Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta Trial by Jury, about a breach claim, was premiered. Bardell v Pickwick was dramatised and performed by amateur societies and in the professional theatre. Law societies around the country staged mock breach trails for entertainment and fundraising. After-dinner speakers drew inspiration from both Dickens and from breach cases, all of which helped to keep references to Pickwick in the public mind.

Despite this, many people would not have been party to the joke. There were public readings of The Pickwick Papers to workers when the instalments were first published, but middle-class families were more likely to have the book in their home. Working-class literacy expanded from the 1870s with the advent of compulsory education and Dickens remained a popular and respected author, but The Pickwick Papers would not have been read in most schools. By the early 20th century, references seem more prolific in the established newspapers, which served a middle-class audience, than in the newer ones which were aimed at workers.

Pickwick had a charmed life and remained in the public eye until the advent of the Second World War as it was publicised in novel ways. The episodic format was particularly suitable for radio broadcasting and it was also filmed for the new cinema industry. Around the centenary of publication in 1937, celebratory exhibitions, competitions and dinners were held.

By the 1940s, occasional questions about the characters were included in newspapers as readers’ queries. Allusions to Bardell v Pickwick still appeared. In 1941, a serious newspaper report about the Nazis quizzing French soldiers on their understanding of National Socialism and the future relations between France and Germany made several references to the trial.

In 1942, a case which involved a Mr Weller as solicitor for a Mrs Bardell who was suing her husband for desertion received disproportionate coverage.

As late as 1949, Mr Pickwick featured in an advertisement for financial services by a major bank, but, by now, Bardell v Pickwick related to a world that had vanished long ago. As Britain grappled with new concerns in the 1950s, and angry young men and rock ’n’ roll became its latest cultural icons, Mr Pickwick and his companions quietly slid from view.

Had Jack the Ripper been caught, his would certainly have been the trial of the century. But Jack eluded his pursuers and, in terms of longevity, column inches, jury verdicts, insider jokes, cultural references and dramatic adaptations it is difficult to think of a real court case which had as much varied coverage as Bardell v Pickwick, or an author who had as much influence as Dickens. For a man who despised so much about the legal processes of his age, he would probably be very gratified.

By 1930, breach of promise cases were rarely brought. The claim was abolished in England in 1970 and Scotland in 1984.