It was the summer of 1897, and in a poor area of Birmingham, children were having to use their imaginations to keep themselves occupied. These children were living in MacDonald Street, a road dissecting the city’s Highgate and Deritend districts; on this particular summer’s day, they gathered together and decided to put on a production of Little Red Riding Hood. They commandeered the street’s communal washhouse to serve as a theatre, moving in a table to be the stage, and sheets for scenery. No theatre was a proper one without footlights, so the children used a candle and a paraffin lamp. They even fashioned costumes for themselves out of paper, and were proud of themselves for their achievements.

Once the stage was set, the children filed in, and locked the door from the inside, so that their parents could not interrupt them and order them outside. Unfortunately – perhaps inevitably – one of the little actors, in his paper outfit, got too close with one of the ‘footlights’, and the costume went up in flames. The children panicked; their noise soon drew adult neighbours to their rescue, but by the time they knocked the door down, four children and a baby they had been looking after had all suffered serious burns.

As this story suggests, children were particularly prone to mishaps. In 1898, four-year-old Minnie Hale of Gloucester died in a tragic accident. It was a June evening, getting dark, when she had been out playing near the junction of Derby Road and Lower Barton Street in the city. She ran out across the junction, and straight into the path of a brewer’s dray. The horse, which was going at around seven miles an hour, stepped on her, although the wheels of the cart it was pulling did not hit her. Her father Wilson Hale, an engine driver for the Midland Railway, gave evidence at her inquest. Minnie had been taken to the local doctor’s surgery, and on hearing she was injured, her father had found her there and taken her to the infirmary. Minnie had turned to her father and said, ‘the gee-gee did it’. Although Minnie had been conscious when found, she died only two hours after being admitted to hospital; a post mortem found that she had several broken ribs and a punctured lung. Her death, though, was deemed to be a result of shock.

Minnie’s death was seen as completely accidental; she had run out into the road, and the carter in charge of the horse had not been able to see her. Another death was also seen as completely accidental, even though, at first reading, it seemed to be the result of neglectful parenting. This case involved a 21-month-old toddler, William Harold Rawlinson, who died in Lincoln in 1894. The child had been tied with string to a chair by its mother, Harriet, a foundry labourer’s wife, who simply intended for her child to stay in the chair without falling out while she was sweeping outside her house – she had previously had the child in the chair and it had slipped out. The toddler, though, slipped through the seat again, and the string caught round its neck, strangling it. Harriet was deemed to be beyond reproach, however, as she had been taking ‘precautions for the safety of her child’ and that she apparently couldn’t have foreseen that her methods would ‘bring about its death’.

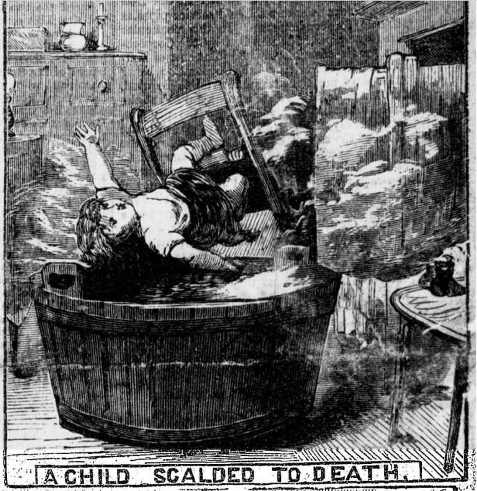

Many of the cases detailed by the newspapers involved those from the lower rungs of the social ladder. Living in poorer, more cramped conditions, these individuals lived lives that were more risky; imagine being in a tiny living room, one that also served as kitchen and possibly even bedroom. Cooking was all done before a fire; to make a cup of tea, a pot or kettle would also need to be put on the fire. It was easy to brush the fire with one’s clothing, with little room to get around, and many were the cases of accidental deaths due to setting clothing on fire. Just a month before the death of Queen Victoria, an 81-year-old woman, Elizabeth Stewart, burned to death in her Glasgow home. She had gone to bed leaving a lit candle on her bedside table. It had set fire to her bed, and by the time a neighbour smelled smoke and broke in with a bucket of water, Elizabeth had already died, and her bed was ‘a mass of flames’. Nearly 40 years earlier, in 1862, a child had burned to death in Manchester when she was using a candle to help her see while she was reading – a spark from the candle had set fire to her dress.

The Victorian newspapers eagerly covered such stories, but stories from outside the UK could be even more horrific, and reported almost with a shudder. In July 1896, for example, the British papers covered a story from Gommant, a rural area within the Autun district of Macon, France. An agricultural labourer had been mowing the fields with a scythe, when his three-year-old son got too near. The father accidentally decapitated his son with the scythe; when he realised what he had done, he left the field, and hanged himself.

This was a typically rural accident; but it was common in industrial Britain to hear of workplace-related accidents. In some areas, such as Birmingham, many labouring class men worked in the gun industry, as barrel filers, polishers, and so on, some of which tasks could be done from home, and which had ample scope for catastrophes. Even when individuals did not work in industry, they could still have accidents related to workplaces. For example, in 1867, a Miss Newsome, originally from Hull, had an accident at the Oaks Colliery in Barnsley. She had been visiting her sister-in-law in the town, and was taken with the idea of visiting the Oaks. She went, and got through fencing that had been put up to stop strangers intruding onto the site. She then entered the engine house, but once there, her dress caught and got wound round the revolving shaft, and she broke her legs trying to extricate herself from the moving machinery.

Intriguing article?

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

When she was found, her clothes were wound so tightly round the shaft that the engine had been brought to a standstill, and her crinoline had to be cut through with a hammer and chisel to free her. She was taken back to her sister-in-law’s house, and a doctor called, but her legs were so mutilated that the broken bones could not be set, and she died. Her death was rather ironic; she had been drawn to visit the colliery as a sightseer following a series of explosions there in December 1866, which resulted in 364 men and boys being killed. Nine months after the accident – and a month before Miss Newsome had died – a body had been found in spoil at the pit, and identified as Parkin Jeffcock, 37, who had volunteered to help rescue the miners back in December 1866, and who, it was suggested, had been blown away some distance by an explosion and his body jammed in amongst pieces of ‘broken corves, old wire rope and materials’.

Nine years after the accident, the well-preserved bodies of another man and boy were found in workings that had been flooded in order to stamp out the fire causes by the explosions; but there were still 32 others unaccounted for even at this time. One man who made money from the 1866 explosion was CW Smith, a Birmingham photographer, who advertised ‘photographs of the late lamented Mr Jeffcock’ for sale for a shilling each, and suitable as a ‘memento’ of the ‘noble volunteer who perished in the recent explosions’.

There were clearly risks to being in particular occupations, such as being a miner; train drivers might also face accidents and disasters. However, there were also some more unusual occupational hazards. In 1887, Patrick Martin was cleaning a culvert at a Coatbridge ironworks when he was overcome by gas; two men went to rescue him and were similarly overcome. They survived – but Patrick never regained consciousness. Two years later, James Turnbull, a 15-year-old boy employed at a Dundee factory, was messing about by a third floor window when he overbalanced and fell out, resulting in serious head injuries that became fatal a few hours later. In 1879, also in Scotland, 18-year-old Sarah Jane Thomson had been employed at the Noble’s Explosive Company’s Chemical Works near Polmont for just two weeks. She was carrying 800 caps, each partly charged with powder, from one part of the factory to another when they all exploded, killing her instantly and ‘scattering her clothes about the place in fragments’. Two other girls had been similarly killed just a year before Sarah Jane’s death.

Leisure activities could also result in accidents and deaths. In 1873, for example, an unemployed 19-year-old from Chelsea, Alfred Hunter, had gone to Brompton Cemetery to see some of his friends, who worked there as gravediggers. He then intended to stand on the cemetery wall in the afternoon, to watch a polo match that was taking place in nearby Lillie Bridge Grounds. However, while he was standing near a newly dug grave, the ground gave way, and poor Alfred ended up buried alive under seven feet of earth. His body was duly recovered by his friends, and taken to the mortuary at Kensington Workhouse.

The Victorian newspapers record various deaths from sports such as running, but also numerous deaths as a result of drink. The danger of drink was widely known and written about, but then as now, many people enjoyed a drink, and didn’t necessarily know when to stop. In 1873, one woman died instantly when the driver of a pianoforte van offered her and her husband a lift home one night in West Hartlepool. All three had been drinking, and as they travelled along – all on top of the vehicle, with no protection, as the driver held onto the horse reins – they started quarrelling, and ended up all rolling off the van into the road. The unfortunate woman’s husband, slater Thomas Lawrence, saw his wife killed as a result of a drunken argument with a stranger.

These various accidents are just a few of those detailed in the pages of 19th-century newspapers, and indicate how dangerous life could be. It didn’t matter whether you lived in a rural community or an urban one, whether you were rich or poor – an accident could occur whenever, and wherever, you were. In Victorian times, you had to be alert all the time to the situation you were in, and whether there could be an accident just waiting to happen.