The production of wool from British sheep had risen and achieved unparalleled success by the early modern era. In the early 1700s Daniel Defoe wrote that English woollen goods were the ‘richest and most valuable manufacture in the world’ and indeed no other industry gained such status, or was carried out so widely or for so long. For centuries, scarcely a town, village or hamlet was not involved at some stage in producing woollen cloth: spinning wheels and hand looms were found in most homes; and fulling operations were as common as grinding corn.

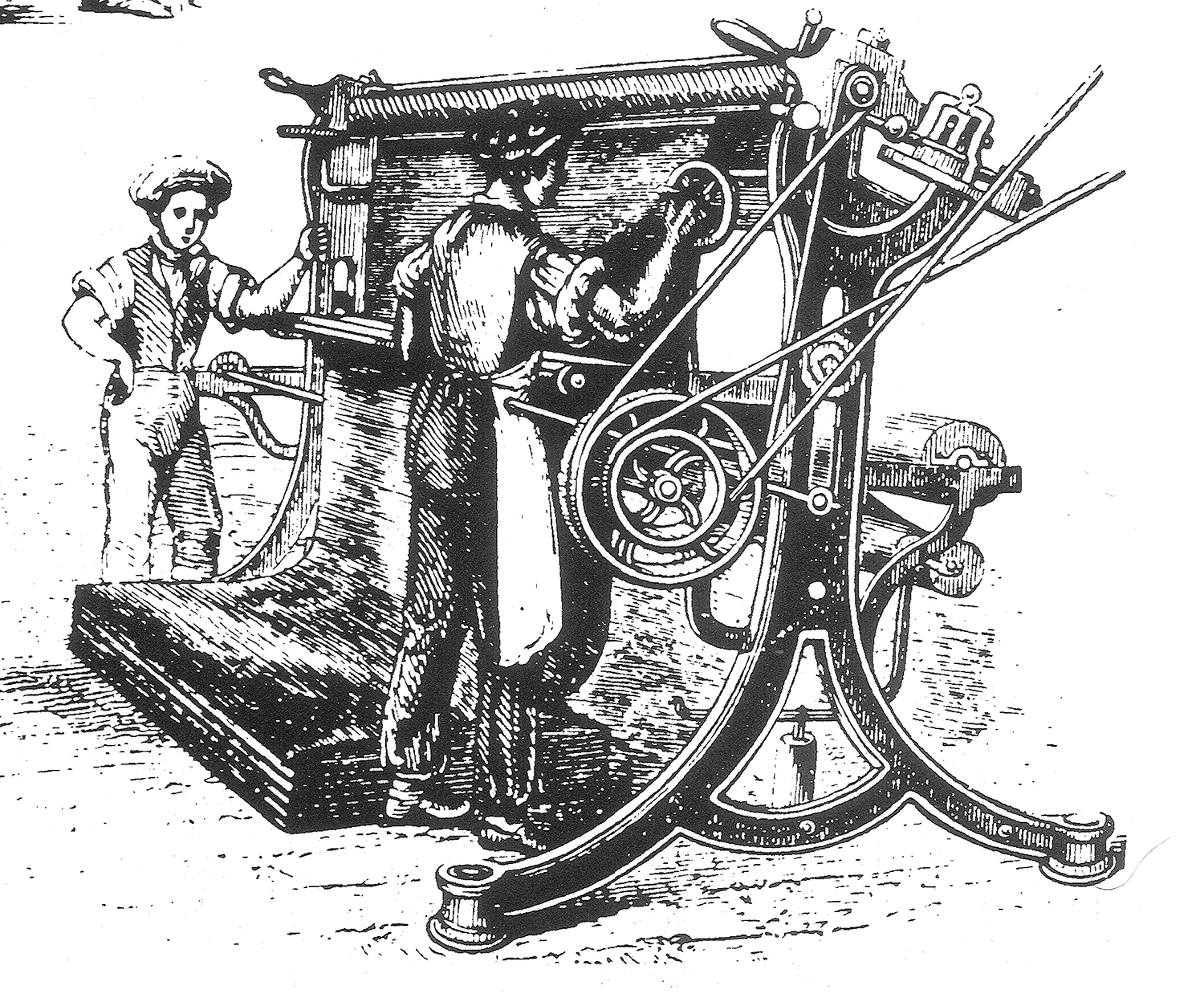

Notwithstanding early factory-like mills established in the late 1500s, until the industrial age the manufacture of woollen cloth remained chiefly a cottage industry. Eventually, however, the revolutionary textile advances of the 1700s and 1800s, meant that fine woollen materials using short-staple fibres and worsted goods using mainly longer-staple fibres could now be mass-produced in power-driven factories. The shift away from domestic production took longer than with most other textile processing, for wool was relatively scarce, expensive, and the combing of worsted fibres not easily replicated by machinery; however, technical issues were largely overcome by the mid-1800s.

The mechanisation of woollen and worsted textiles transformed the industry’s once-widespread geographical distribution and, from the late 1700s, manufacture was increasingly concentrated in the West Riding of Yorkshire, a key area that already, by 1770, accounted for over half of Britain’s entire textile export trade. As many of our ancestors sought work in the prospering woollen mills, the population of the West Riding soared from 572,000 in 1801 to 1,325,000 in 1851, old centres like Leeds and Halifax rapidly expanding and new towns like Huddersfield rising up from tiny hamlets. Whereas early mills were located near water, often away from centres of population, once steam-driven engines came into general use mills and the towns that grew around them became crowded, unsanitary urban hubs where families crammed into dark, closely built homes in narrow streets without sewers, and mud underfoot.

Intriguing article?

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

Conditions in early mills were equally deplorable: long hours, low wages, hazardous working environments and a strict factory schedule dictated by the unrelenting steam machine. Entire families laboured, including young children, whose ill treatment provoked concern, helping to fuel the Factory Movement. Among the worst workplaces were the ‘shoddy’ mills first established in the early 1800s in locations like Batley and Dewsbury, where ground-up rags were reworked into cheap mixed cotton and worsted fabrics and where thick, clinging dust and fibres choked the atmosphere, leading workers to adopt protective mouth coverings. The plight of woollen millworkers led diverse Yorkshire reformers to exert pressure on mill masters, their leader and ceaseless campaigner Richard Oastler idolised as the ‘Factory King’.