For generations a veil of secrecy had hidden the secret of my great, great, great grandmother’s existence. A fabricated story suggested she came from a family of gypsies, but the truth was uncovered when I came across a list of prisoners from Somerset, England in 1844 which included the name of Jane (Pavey) Cuff of Combe St. Nicholas. The discovery moved me to follow Jane Cuff’s life trail. A pilgrimage which took several years of planning and research and which eventually led to the Cascades Female Convicts Factory in Tasmania.

From the Somerset Records office, I discovered that Jane Pavey was born in 1799 in Whitestaunton, Somerset, England, one of nine children to Matthew Pavey, an agricultural labourer, and Jane (or Joan) Pavey.

In 1827 Jane gave birth to an illegitimate son, Levi Hitchcock Pavey. Three years later she married William Cuff, a local mason from the neighbouring parish of Combe St. Nicholas.

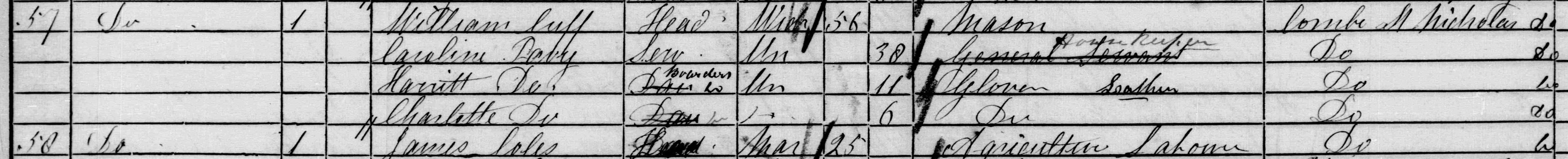

By the 1841 Census, Jane is seen with her new family living in Stantway in Combe St. Nicholas with four more children; John, Charlotte, James and William.

In July of the following year, Jane’s husband, William Cuff, is found serving six weeks hard labour in the Wilton Gaol for absconding from his wife and family, after which he was returned to Combe St. Nicholas.

On the 12th of December 1843 Jane Cuff was admitted to Ilchester Gaol for two weeks hard labour for stealing potatoes.

She subsequently appears on the Calendar of Prisoners for trial for the Lent Assizes, Western Circuit, held at Taunton Castle on Saturday 30 March 1844. On this occasion, she was being tried for arson.

The Taunton Courier newspaper reported on the proceedings of Jane’s trial as follows:

Jane Cuff was indicted for maliciously setting fire to a stack of hay, on the 30th March, the property of Alexander Dampier. It appeared that Mr. Dampier was a farmer at Combe St. Nicholas, and that earlier in the month of March the prosecutor had caught the prisoner’s daughter stealing his turnips, and he threatened to have her up before the magistrates, upon which the prisoner said, “She would be d___d if she did not do for Dampier.” On the evening of the 30th of March a rick belonging to Mr. Dampier, near the prisoner’s cottage, was discovered to be on fire. Shortly after the prisoner came home, and a neighbour went into the cottage, and said to the prisoner, “What a bad misfortune it is.” The prisoner replied that it was not. The neighbour then said- – “How lucky it was the wind was not the other way.” The prisoner said she knew what way the wind was, for she had done it herself; she told Dampier she would do for him and she had. It turned out that this neighbour (a woman) and her husband had been in gaol for stealing. The learned Judge said the only question for the jury was, whether they believed that witness? If they did, they would find the prisoner guilty, but if they did not they would then acquit her. The jury found the prisoner Guilty. Sentence deferred.

Following the trial, on 3rd April 1844 Jane was committed to Ilchester Gaol from Taunton, convicted for arson and sentenced to ‘Transport for Life’.

The ship’s three months journey included attempted suicide, seizures, miscarriages, fever, syphilis and scabies.

The Crown Minutes for the 1844 West Somerset Circuit which are held at The National Archives in Kew record that:

The jurors for our Lady the Queen upon their Oath present that Jane Cuff, pro se Guilty, late of the parish of Combe St. Nicholas in the County of Somerset….on the thirtieth day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty four at the parish aforesaid in the said County feloniously unlawfully and maliciously did set fire to a certain Stack of Hay of Alexander Dampier there and then being against the form of the statutes in such case made and provided and against the peace of our Lady the Queen her Crown and Dignity.

Jane Cuff was transported with 191 other female prisoners on the hulk ‘Tasmania’ departing London, England on 3rd September 1844 bound for Van Diemen’s Land, arriving on the 20th of December.

According to the ship’s surgeon’s log, fellow passengers of Jane were treated for a range of ailments during the ship’s three month’s journey including; abdominal rupture, effects of syphilis, wounds, abortion, attempted suicide, vaginal discharges and fistulas, seizures, miscarriages, diarrhea, fever, scalds & burns and scabies.

It would be a greater mercy to hang them at home than send them here.

Upon arriving in Van Diemen’s Land (Hobart, Tasmania) Jane was brought to Brickfields Depot from where she was assigned to the Cascades Female Factory which served as the British penal institute for women convicts.

Life in Van Dieman’s land was colourfully described in extracts from a letter published in the Irish newspaper, The Freeman’s Journal, on 10 February 1835 by a Kilkenny gentleman:

I am most happy, as an opportunity offers for London, to send you an account of this d____d country; and I hope you’ll make it known to all persons who purpose to emigrate to those colonies (which you ands I were led to think were the best) that Ireland, bad as it is, is better than here. —

There is neither employment for free people, or pity for the affected, the hearts of all are callous to every feeling save that of avarice.

This country is inhabited by persons who have been transported for the last 30 years; and they have land granted them on their freedom, but their morals are quite depraved. Each person in town and country that holds property of any description are allowed prisoners to do their work, and if they do not do it, complaint is made, and they are cruelly lashed every day till they give full satisfaction to their master. I wish it was generally known in Ireland by the unfortunate and misguided portion of my countrymen, how transports are dealt with here; and I am sure they would commit no offence to subject them to transportation. I assure you in the most positive manner, it would be a greater mercy to hang them at home than send them here.

In 2006, I travelled to Hobart, Tasmania, to visit what remains of the Cascades Female Convicts Factory. The Archives Office of Tasmania was a trove of information on individual convicts where I found Jane Cuff’s convict conduct record describing her as being 5 foot 4 inches tall with a sallow complexion, round face, and a small head with brown hair. Her eyes were grey and she had a small nose and round chin. At 45 years of age she had lost several front teeth and both hands were crippled from arthritis.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

I stood on the docks in Hobart harbour at the very place where Jane’s ship would have moored after it completed its journey. I tried to imagine the scene in December of 1844 when she was led off the hulk to be taken to the ‘female factory’ outside of town.

In her memory, I walked the distance to the remains of the site of which she was to live over the next seventeen years. The roadway to Cascades is now lined with houses, shops and office buildings. Eventually I came to a small residential area situated in the shadow of Mount Wellington and the Cascades Brewery where the ancient Hobart Rivulet runs off from the mountain cascades that gave the place its name.

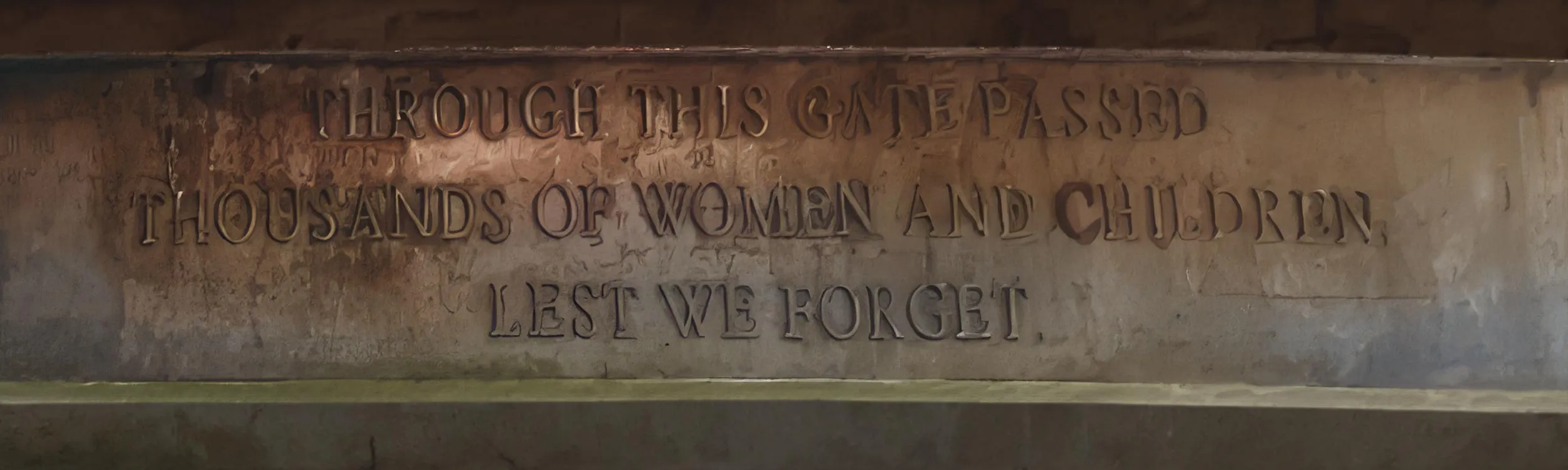

Standing sentry at the edge of the stream are the remains of the prison. The long stretch of foreboding stone wall

betrays its former identity. There is a great opening in the wall, which would be the gateway that Jane would have

entered. Carved on the lintel are the poignant words; Through this gate passed thousands of woman and children.

Lest we forget.

The open, walled space within the gate is now devoid of buildings or anything that indicates the massive complex of rooms and yards that once filled it. The inner walls and buildings have long since been dismantled and the stones used for other things. The foundations and floors remain somewhere deep beneath the sod, now covered by tiny wildflowers.

Over the next 17 years, Jane Cuff worked within this complex alternating between the Cascades Female Factory house of correction and its infirmary.

On the 31st of January 1861 Jane Pavey Cuff succumbed to chronic bronchitis and died at the Invalid Depot at the Cascades Female Factory at 61 years of age.

I tried to identify the exact spot where she was buried, but sadly she lay somewhere in a pauper’s grave outside the prison walls in an area now covered with modern homes with yards and swing sets and driveways.

I came there hoping to find her and to tell her what happened to her family after she were taken away from Combe St. Nicholas.

After Jane was transported, her husband in Somerset referred to himself as a “Widow”. Her younger sister, Caroline, moved in to take care of her children and went on to have two of her own by Jane’s husband.

In later years, the sister went to live with her daughter, but the husband ended up in the Workhouse in Chard where he died in 1879.

As far as her children went, her firstborn son Levi Pavey remained in Combe St. Nicholas working at the local toothbrush factory. The daughter Charlotte (the one that stole the turnips) died from infectious Scarletina at the tender age of 15.

Son, John, moved to Curry Mallet and raised a family, and son William remained in Combe St. Nicholas working as a gardener and raising a very large family.

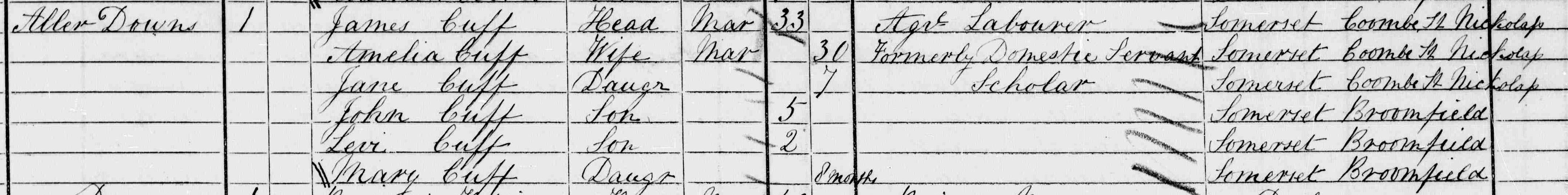

Son, James Cuff, my ancestor, left Combe St. Nicholas and moved to Devonshire, then to Wales and finally to Oldham in Lancashire. His seven children all married and had children of their own.

My grandmother remembered him well from when she was a young lady. He died in 1912. He was short of stature like his mother and worked sometimes as a field labourer and sometimes as a chimney sweep. Shortly after he died my grandmother immigrated to Cambridge, Massachusetts in America where I was born in 1953.

Jane Cuff never saw her children grow up and no doubt never knew what happened to them. They entered their adulthoods without benefit of their mother’s support. She also never had the chance to meet her grandchildren, which is the privilege of most grandmothers.

All in all there were twenty three of her grandchildren that lived to adulthood. They were domestic servants, constables, housekeepers, factory and farm workers, blacksmiths, locomotive engineers, soldiers, and dock workers playing essential roles in the building of the British Empire.

A number of these grandchildren made the decision to leave the homeland and immigrate to new lands and to begin new lives. Some went to the United States, some to South Africa, some to Australia and coincidentally one grandchild even made his way to Hobart with his family as Assisted Immigrants in 1922. Living at Bonnington Road, he would have been completely unaware that he was a mere mile or so from the defunct Cascades Female Factory which had been his grandmother’s prison for the last years of her life.

By 1922 Hobart had become a thriving port largely built from the sweat and toil of convicts like Jane and populated by their descendants.

Jane Cuff’s descendants now number in the hundreds spanning the globe. But she would never be aware of this or know what role she played in creating my family and the accumulated contributions that our family has made to our local society and society at large. I am happy to report that Jane’s diaspora have continued the family line and carried on with values and energy that I believe she would be proud of. Her line produced businessmen and businesswomen, ministers, doctors, police officers, railway workers, teachers, home-makers and a legion of professions and talents that have helped build a new world that she would never see.

I came to Cascades Female Factory to honour Jane’s life and to mark her death. She is now part of the story of the women of the Cascades Female Factory that found themselves in such terrible circumstances but became the seed for a new beginning of generations to come.