The life of Catherine Cookson could easily have been lifted from the pages of one of her best-selling novels, an illegitimate child raised in the North East in the early 1900s, who dreamed of a better life, married a school master and eventually became one of Britain’s wealthiest women. We take a look at the amazing story of the girl from South Shields who became the most widely read novelist in the UK with sales reaching over 100 million…

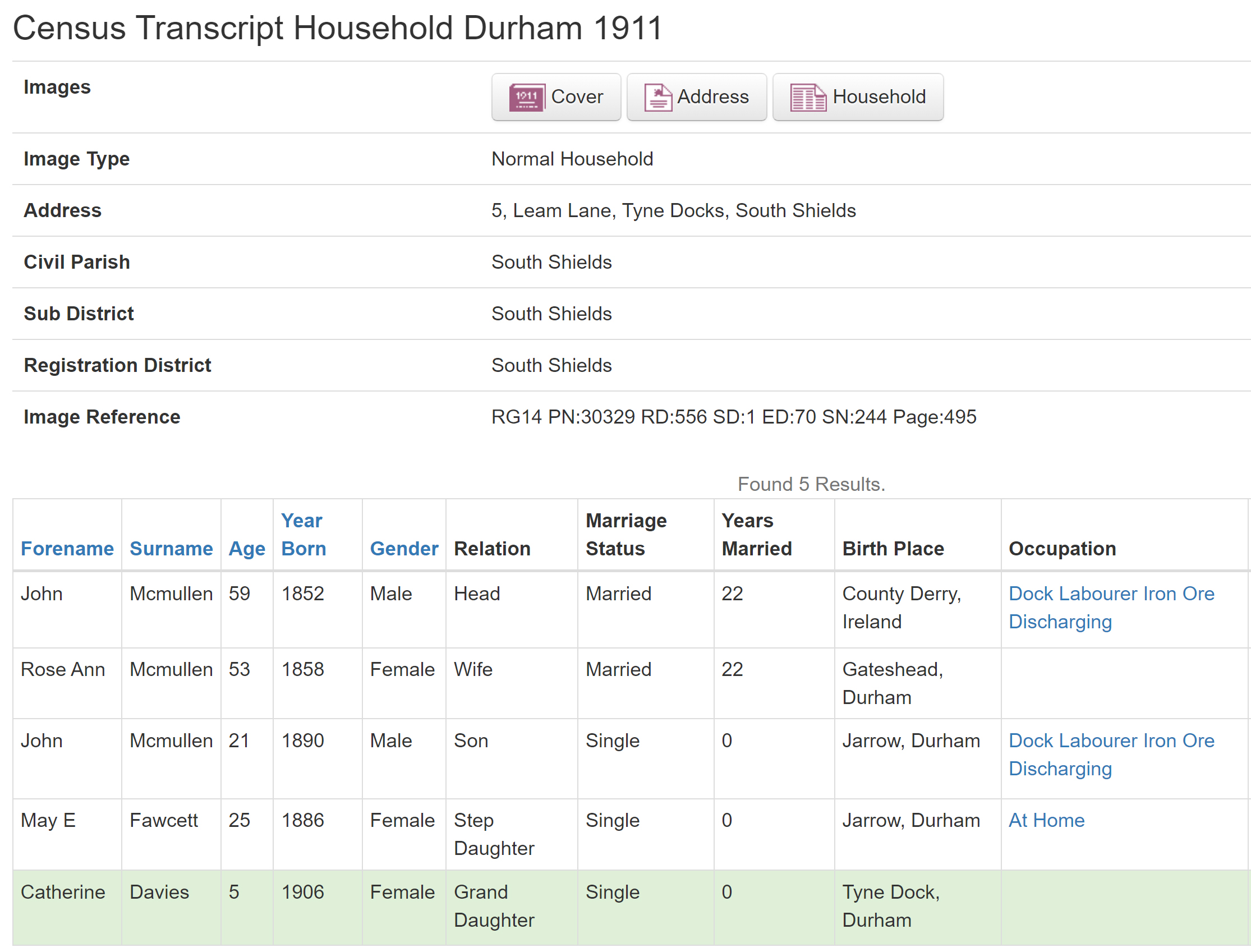

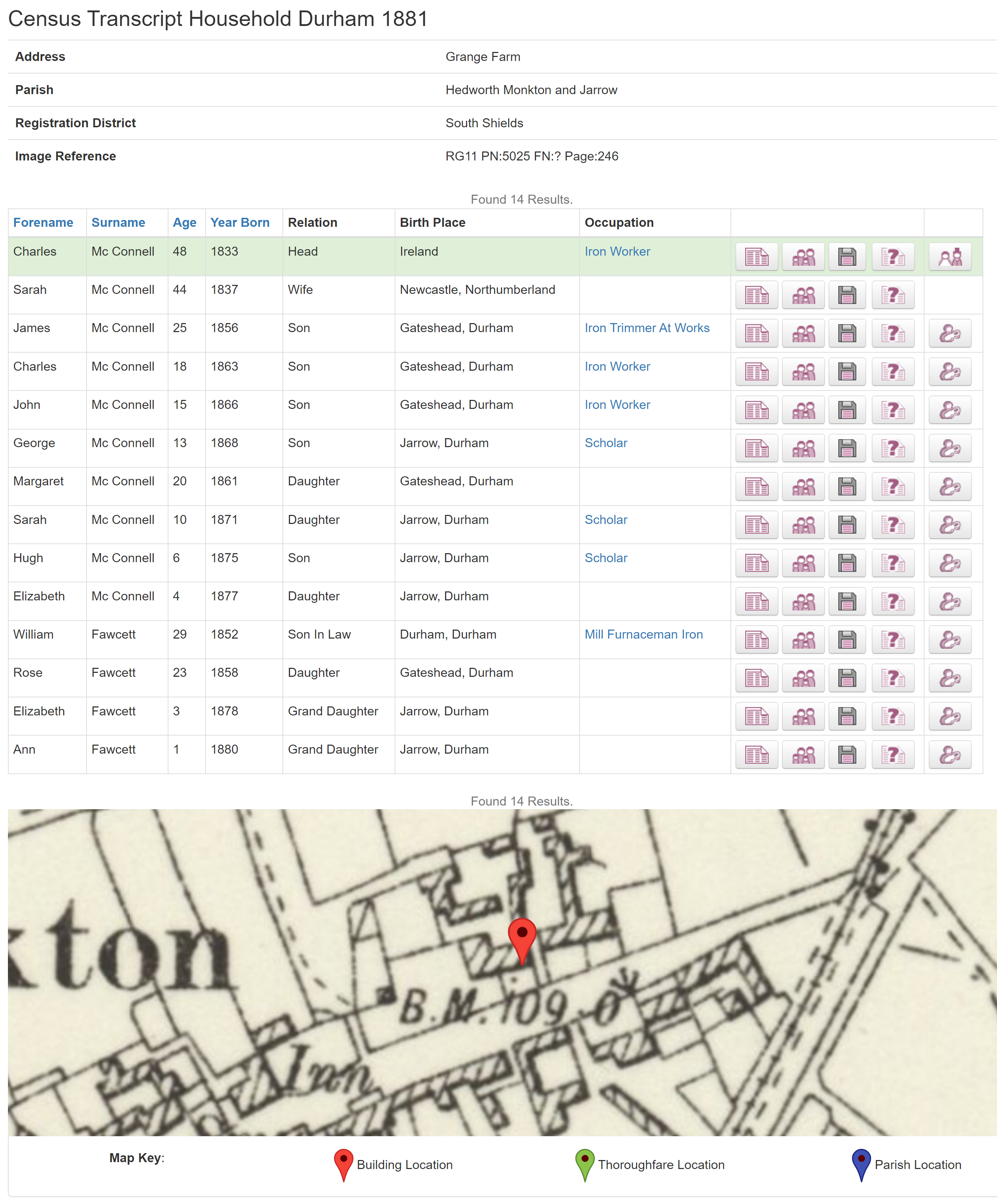

Catherine was born in Tyne Dock, South Shields in June 1906, the illegitimate daughter of Kate Fawcett, a barmaid with little income and a weakness for alcohol. Catherine was raised by her grandmother Rose McMullen and step-grandfather John McMullen, in the poverty stricken surroundings of Jarrow. She spent most of her childhood believing that her mother Kate was her sister, only discovering the truth of her parentage at the age of seven. Her father was later identified as Alexander Davies, a gambler and bigamist from Lancashire.

She learned the truth about her parentage at the age of seven

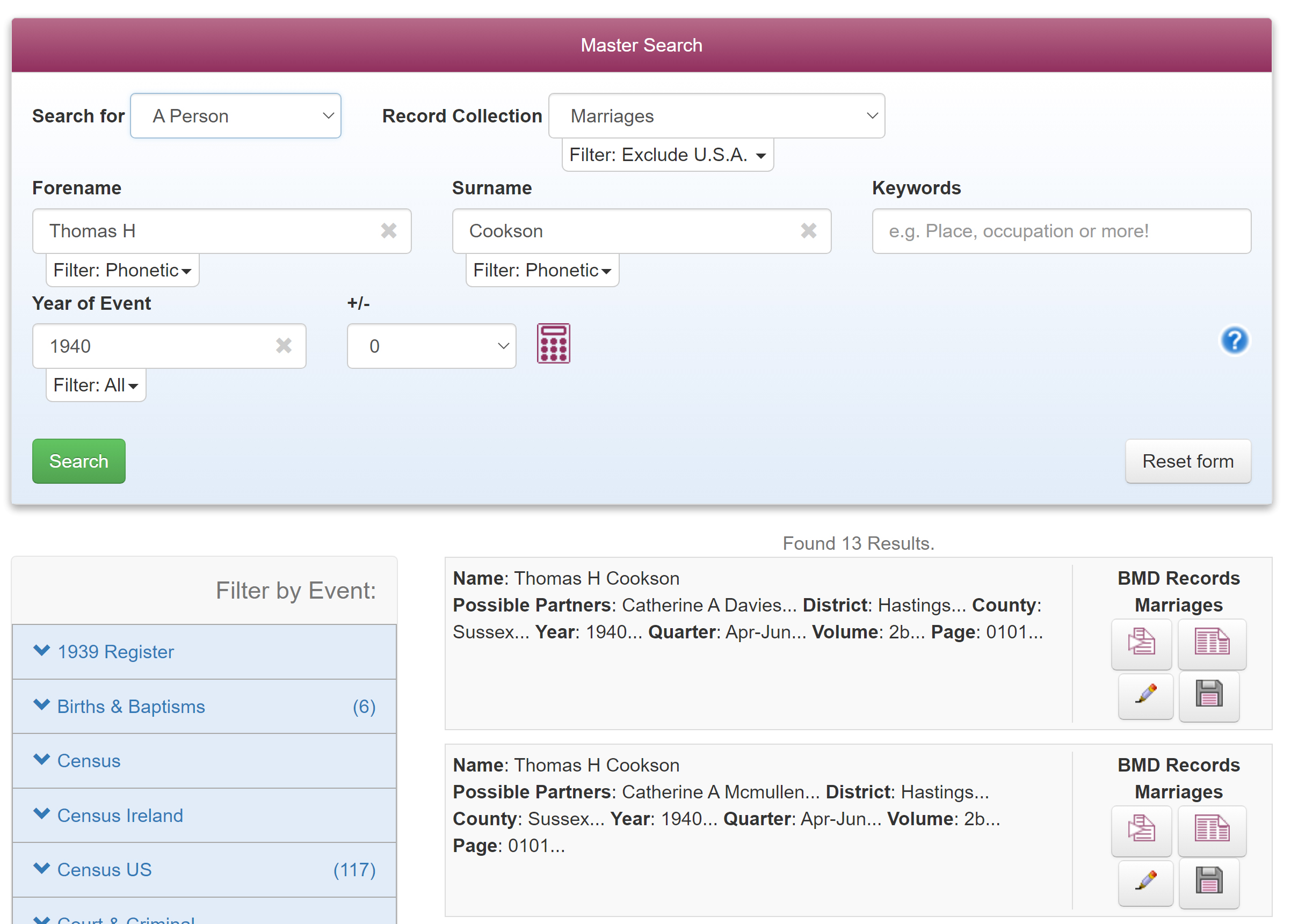

Catherine left school at 13 and went into domestic service for a wealthy family. It was here that the differences between the classes were made apparent to Catherine, and class conflict became a common issue in many of her novels. She later took a laundry job in Harton workhouse in 1924, where she saw society at its worst and vowed to leave her past behind and never come back. After taking voice projection lessons to over-come her strong Geordie accent and spending hours reading in the public library, Catherine travelled south to Hastings in 1929 and took on a position as laundry manager, saving all of her money to buy a large Victorian house. Her idea was to create a lodging house, which would provide with a comfortable income and keep her far away from her past. One of her lodgers happened to be a teacher at Hastings Grammar School, named Tom Cookson. The couple fell in love during the Second World War and were married in 1940.

Searching for the marriage of Tom & Catherine on TheGenealogist.co.uk shows she is registered under both her father’s name ‘Davies’ and also the family name she was raised with ‘McMullen’.

Catherine suffered four miscarriages late in pregnancy, and discovered she had a rare hereditary blood disorder, telangiectasia, which caused bleeding and anaemia. As a result she was unable to have children and suffered a nervous breakdown, which made her suicidal and took her a decade to recover from. Catherine began writing as therapy for her depression and joined a writing group in Hastings. She’d always had a keen interest in writing, and wrote her first short story, ‘The Irish Wild Girl’, when she was eleven. She had sent it to the South Shields Gazette but it was returned three days later.

Her first novel to be published as an adult writer was ‘Kate Hannigan’ in 1950, which was partly based on her own family, as Kate becomes pregnant by an upper middle class man and the baby is raised by her parents believing that Kate is actually her sister. Although her novels were often classed as ‘romance’, Catherine felt they were also historical as she carefully researched each one, and based her stories on people she knew and conditions that she had experienced. The novel ‘Colour Blind’ was a classic example of this, confronting issues of class tension, as well as race and unemployment. Many of her stories are set against a background of poverty in the North East in mines, shipyards, farms and the surrounding rural areas, with the heroine over-coming her class restrictions through education. Her home town of Jarrow was an industrial centre for ship-building and coal mining. ‘Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company Limited’, founded in 1852, was the first armour-plate manufacturer in the world and produced around 1,000 ships before it closed in 1934. Census records on TheGenealogist show that most of Catherine’s family were employed by Palmers or worked at the coal mines.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

She continued to write for the rest of her life, and published nearly 100 novels in total. These were translated into at least twenty different languages, with 18 adapted for television between 1999 and 2001, and others adapted into films. The television adaptation of ‘The Black Velvet Gown’ won an International Emmy for Best Drama in 1991. Catherine’s husband Tom also helped her on the path to success, since many people found it difficult to follow her North East accent, school master Tom acted as her private secretary and helped with grammar and spelling in all her novels.

Although Catherine had vowed in 1929 never to return to the North East, she decided to go back in 1976, to confront her past and use her wealth to help others who were not as fortunate. Catherine donated money to many causes, with medical research receiving the largest share. She gave £800,000 in 1985 to the University of Newcastle, with £40,000 to be spent on a new laser to treat bleeding disorders. She had also previously donated £20,000 to the University’s Hatton Gallery and £32,000 to their library. As thanks, the University set up a lectureship in haematology and presented her with an honorary degree. She was placed on the Queen’s honours list in 1985 and received an OBE, which was elevated to CBE in 1993, making her Dame Catherine Cookson.

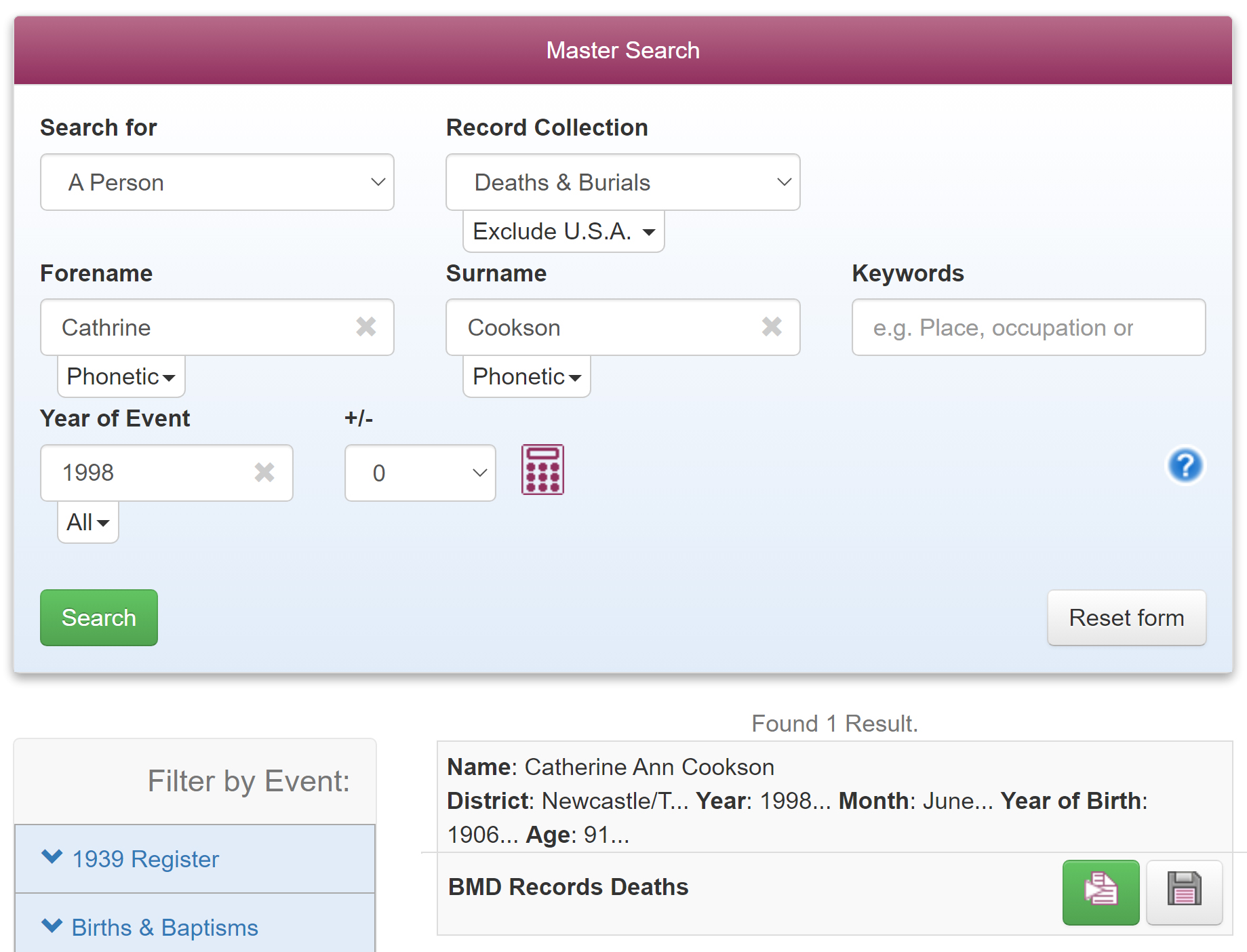

In later life, Catherine and Tom moved to different areas of the North East before returning to Jesmond when her health started to deteriorate. She was bed ridden for the last few years of her life and died at home in 1998 at the age of 91. Tom Cookson died 17 days later, on the 28th of June 1998.