With the announcement of a surprise General Election in the United Kingdom this June, TheGenealogist has been looking at how our ancestors elected their governments or more precisely seeing how many of our forebears would have been denied the vote at all. Today we expect democracy to include a secret ballot, universal suffrage and that one person has one vote for a candidate to represent them in parliament. In the past, however, whether you qualified to cast a vote in the election of an administration for the country was not based on age alone but also on your sex and on what land you owned. Universities could also return their own M.Ps and so graduates would have had a vote for a candidate in the constituency where they lived and another vote for a candidate representing their University so giving them two representatives in the House of Commons.

Until the Reform act of 1832 M.Ps could be returned to parliament from a nomination borough or proprietorial borough better known as a rotten or pocket borough. These were constituencies where a very small number of electors were used by the patron of the area to secure their candidate’s election to an unrepresentative House of Commons. With there being no secret ballot until 1872, the small number of electorate in a pocket borough were usually subject to control by the ‘owner’ of the borough and so were easily persuaded to vote for his preference in candidate. Rotten boroughs had come about with the movement of the population away from previously thriving centres to new areas and towns. By moving away, the citizens had made the once important borough that had previously justified the sending of Members to Parliament, no longer morally legitimate. This was compounded by the under representation of the new industrial towns that were growing in population all the time. Until reform was introduced, the rotten boroughs would continued to elect M.Ps to Westminster and so were the ultimate ‘safe seat’ for an M.P. to have. When we think of rotten boroughs, Old Sarum springs to mind. With nobody actually living there, in the 1802 General Election its five voters sent two Members of Parliament to Westminster. This situation was as a result of it historically having once been the site of a Cathedral, before the building of the New Sarum Cathedral in nearby Salisbury and the population migrating to the new city.

![Old Sarum by John Constable [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/images/featured-articles/2017/00491/apr17-vote1.jpg)

Many of these rotten boroughs were controlled by landowners and peers who, if they were already members of the House of Lords, could offer the seats in Parliament to like-minded friends or relations and increase the influence that they had in the Palace of Westminster. Those who were not Lords could sit in parliament themselves as an M.P. and so the landed class gained over representation at the expense of the rest of the population.

The history of Parliament stretches back to 1265 when Simon de Montfort, the 6th Earl of Leicester, sent out representatives to each county of England and to a number of boroughs, without the King’s approval. His aim was to add weight to his and the other barons stand against King Henry III, and his parliament was probably quite a partisan assembly. Nonetheless, from this gathering has grown the mother of Parliaments and by 1295 it had evolved to a state where two burgesses from each town and two knights from each shire would go to represent their areas in the assembly. Apart from some modifications that were made in the Tudor period, this would remain as the basic shape of parliament until the reform campaigns of the 19th century. In England, King Henry VI established in 1432 that only the landowners of property that had a value of at least forty shillings were entitled to vote. As this was a significant sum, most of our ancestors would have been immediately disenfranchised by this requirement.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

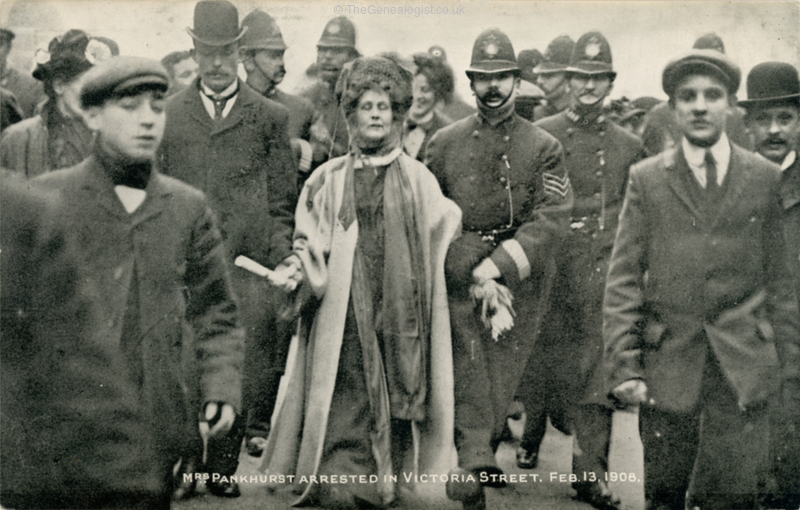

The idea that all men, let alone women, should have the vote is comparatively recent in historical terms. The Reform Act 1832 was responsible for extending the right to vote to adult males who rented properties of a certain value and so opened up the franchise to 1 in 7 males. Then the Reform Act of 1867 enfranchised men from the urban areas, but only those who met a property qualification. The imbalance between the countryside and urban areas was later addressed by the Representation of the People Act 1884. Between 1885 and 1918 saw the rise of the women’s suffrage movement aiming to get the vote for women. But this was put on hold for the duration of the First World War and it was not until 1928 that all women were finally entitled to vote though a small number with property had gained the franchise in 1918 with the Representation of the People act of that year.

The ramifications of World War I had persuaded the government to dramatically expand the right to vote. The previously disenfranchised men, who had fought for their country in the war, were now able to vote for the first time provided they were aged over 21. The property qualifications was now abandoned as a means of deciding if a man could vote. And the clamor of those women who helped in war effort by working in the factories and elsewhere, was now hard to ignore. While males did not need to own property to be entitled to cast their ballot, it was not the same for women. Votes were only given to 40% of the adult female population those women with property and who were over the age of 30. This reform had the effect of increasing the electorate of the United Kingdom from 7.7 million to 21.4 million, with women now being 8.5 million of the electorate. 1928 saw another act that finally brought equal suffrage for women with their male compatriots and also brought the voting age down to 21 with no property requirements at all for any type of voter. Today the age that you can vote is 18 or older, but that reform was introduced only in 1969.

As democracy swings into action again in June, with universal suffrage for those over the age of 18 being considered the norm, it is worth considering how not many of our ancestors would ever have been given the chance to have cast their ballot in an effort to elect a government of their own choice. To mark the occasion TheGenealogist has added to its Polls and Electoral records by publishing online a new collection of Poll books ranging from the late 19th century to the early 20th century and covering 35 different registers of people who were entitled to vote in Wakefield, West Yorkshire plus other constituencies situated in Hampshire, Gloucestershire, Somerset and New Westminster in Canada. This new release bolsters the millions of Poll Books, Electoral Rolls and even some modern records that are already available to search on TheGenealogist and can be especially useful for family historians researching their ancestors’ lives. In some cases, before the introduction of the secret ballot, a record may even reveal your ancestors political persuasion as the way they voted would as a matter of course have been noted in the record. Thankfully that doesn’t happen today!