Paralympic gold medallist Jonnie Peacock shot to fame when he won the 100m in 2012 at the age of just 19. Because his parents separated when he was young, Jonnie’s knowledge is greater about his mother’s side of the family than about his father’s. Jonnie has always been fascinated by his maternal grandfather, Johnnie Roberts, a keen footballer who died in 1992 just before Jonnie was born. On his paternal line he knows very little other than that they were from Cambridgeshire.

Jonnie begins his genealogical quest by going to visit his mum in Doddington, Cambridgeshire. He wanted to find out from her as much as he could about his maternal grandfather especially which team he had played for and also how good he was.

Jonnie’s mother shows him a scrapbook which had been made by his grandfather’s mother and which detailed his ancestor’s footballing exploits. Jonnie discovers that his grandfather was a skilled goal scorer as a young man, and because of this he is mentioned in a number of local press clippings.

‘Eighth hat trick for Roberts. Seven goals last Saturday. Roberts nets 11… Johnnie Roberts, the league’s leading marksman took his aggregate today to 63 goals. If Roberts continues as he started, a new astronomical record could be anticipated.’

Jonnie’s mum recounts a story that tells of his grandfather coming to the attention of a scout from Leeds who attempted to ask Johnnie Roberts to come for a trial. It seems that Johnnie’s father turned the scout away as he wanted his son to get an apprenticeship in a trade such painting and decorating.

To continue his search, Jonnie next headed to the North West of England to try to discover exactly how good a footballer his grandfather Johnnie Roberts had been. Jonnie has a meeting with local football expert Barry Lenton who has some press cuttings relating to his grandfather. These reveal that Johnnie Roberts not only broke the goal record that he had been chasing, but he also got another chance for trial at Leeds. While there were no records to be found that revealed how the trial went, Barry Lenton explains that the lower pay of footballers in the 1960s would mean that Johnnie Roberts would most likely not have wanted to risk losing the wage that he was earning as a painter and decorator. It may have been for this reason that he went to play for the local amateur team of Burscough FC instead.

So he would have still been a painter and decorator but he still loved football so he had to do it somewhere… And he’d come here to try and play. He could have been the Jamie Vardy…!

For the first time, Jonnie pays a visit to his grandfather’s grave in Bootle, Liverpool to pay his respects.

Maybe in another life…if one or two things had gone the right way, it could have been him. That’s sport, we all know that. That’s the same with me: if one thing had gone differently, I don’t think I’d have achieved anything that I achieved…

Jonnie then heads to Liverpool to see if he could find out why Johnnie Roberts’ father, Edward, had put a barrier in the way of his son’s chance of a trial at Leeds when he was a teenager. Research reveals that Edward’s father, Isaac, worked at the local docks as well.

Who Do You Think You Are? arranges for Jonnie to meet medical and social historian Sally Sheard who takes him to visit Bootle and the street there in which Isaac and Edward had once lived now an industrial estate. In World War II some of the slum housing had been bombed and then other houses were cleared to enable the building of the estate that now stands there.

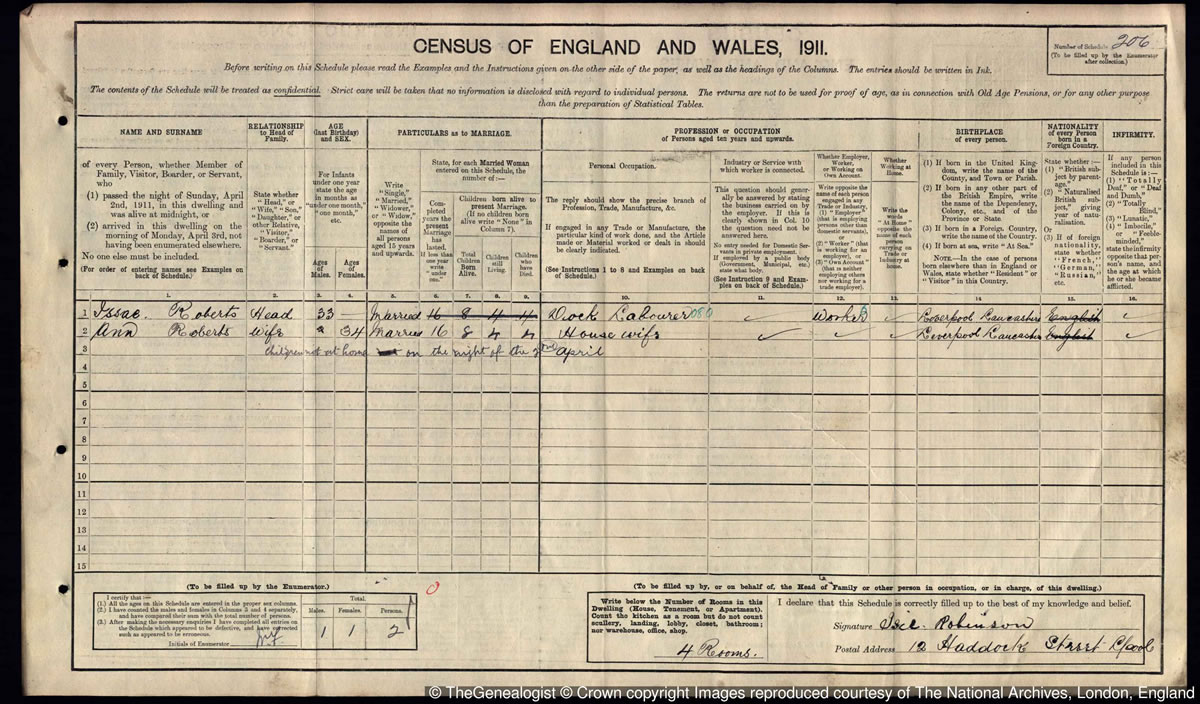

By looking at the 1911 census, Jonnie’s great-grandfather Isaac and great-grandmother Ann can be seen to have lived on Haddock St. By viewing the image on TheGenealogist we can see that a note explains that the children are not there on census night. The document tells us that Isaac and his wife Anne had eight children, including Edward. Sadly four of the children had died by the time of the census. Edward’s brother George’s death certificate lists his cause of death as “diarrhoea and teething issues”. It turns out that five of Edward’s siblings died in childhood and they had diseases linked to poverty in early 20th century Britain such as gastro-enteritis, typhoid, tuberculosis and bronchitis all of which would be curable today by modern medicine.

I can’t imagine going through that, what that must have been like for them as parents

Jonnie is able to take a look at his great-grandparents’ Edward and Mary’s marriage certificate. This document shows him that by the time the wedding took place both the father of the groom and that of the bride had already died. Using this information leads Jonnie to then look at Isaac’s death certificate from March 1928 which reveals an interesting cause of death: “Anthrax accidentally contracted whilst working on board a ship”.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

I don’t know much about anthrax and I don’t know how you can accidentally catch it! I want to find out why he died.

Jonnie is able to meet Helen Doe, a historian, who helps him find out more about why his great-great-grandfather Isaac had died in this way. The first document they look at was the customs bill for a ship named the SS Burgandy that Isaac worked on as a docker in the Alexandra Dock. This vessel’s cargo included bags of fertiliser consisting of dried blood and bones and this would probably have carried anthrax and led to Isaac’s demise.

To follow up on this information Jonnie goes to visit the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine to meet Dr Nick Beeching. The school had been set up in 1898 in order to research treatments for the number of diseases entering the country via Liverpool docks. Anthrax was one such disease weaponised by nations before WWII and Britain had run its own tests using sheep on an island off Scotland in 1942. But Isaac’s death from anthrax was long before this in 1928. The inquest into Isaac’s death noted reports that he had started complaining of ill health after showing his wife a pimple that had appeared under his chin. Dr Beeching tells Jonnie in the Who Do You Think You Are? programme that the treatments at the time had reduced the anthrax mortality rate down to around 10%. Isaac, however, had waited for seven days before he had entered hospital and so reducing his chances dramatically. It was more normal to endure just two or three days of symptoms at most before entering hospital. The assumption is that he needed to carry on working and so delayed going for treatment.

That’s crazy – just pushed himself.

Jonnie goes to see Fazakerly hospital in Liverpool, where Isaac died four short hours after being admitted.

Obviously Anthrax was a blood poisoning disease. What I had when I was 5 was a blood poisoning disease but, luckily, we were 100 years later and we had the NHS

Edward lost over half of his brothers and sisters…he lost his father. That’s why he was such a tough, hard man… I think he wanted the best for his family and I think it’s completely understandable him kind of standing in his way in the football sense.

The family’s come a long way since the last 100 years and I think a lot of that has to do with Edward and how he pushed John to a better life.

Jonnie’s Paternal line

Jonnie goes back to Cambridgeshire so that he can continue his journey by now finding out more about his dad’s side of the family. To discover more he meets up with his paternal grandfather David who shows Jonnie some old family photos dating back to Jonnie’s great-great-great-grandmother. What is known about her is that she was determined that her maiden name, Voss, should be passed down in the family and so she offered her daughter and son-in-law £100 for each grandchild they gave the name Voss to. Unfortunately Jonnie’s grandfather, David, doesn’t know the first name of Jonnie’s 3x great-grandmother nor can he explain why she was so determined to keep her maiden name going.

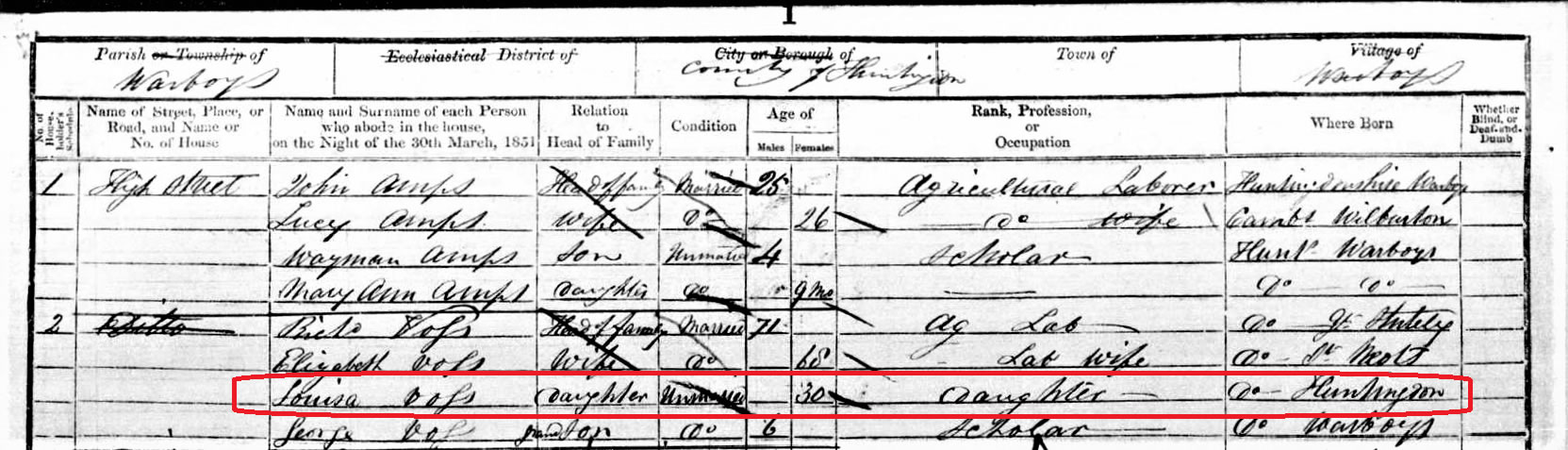

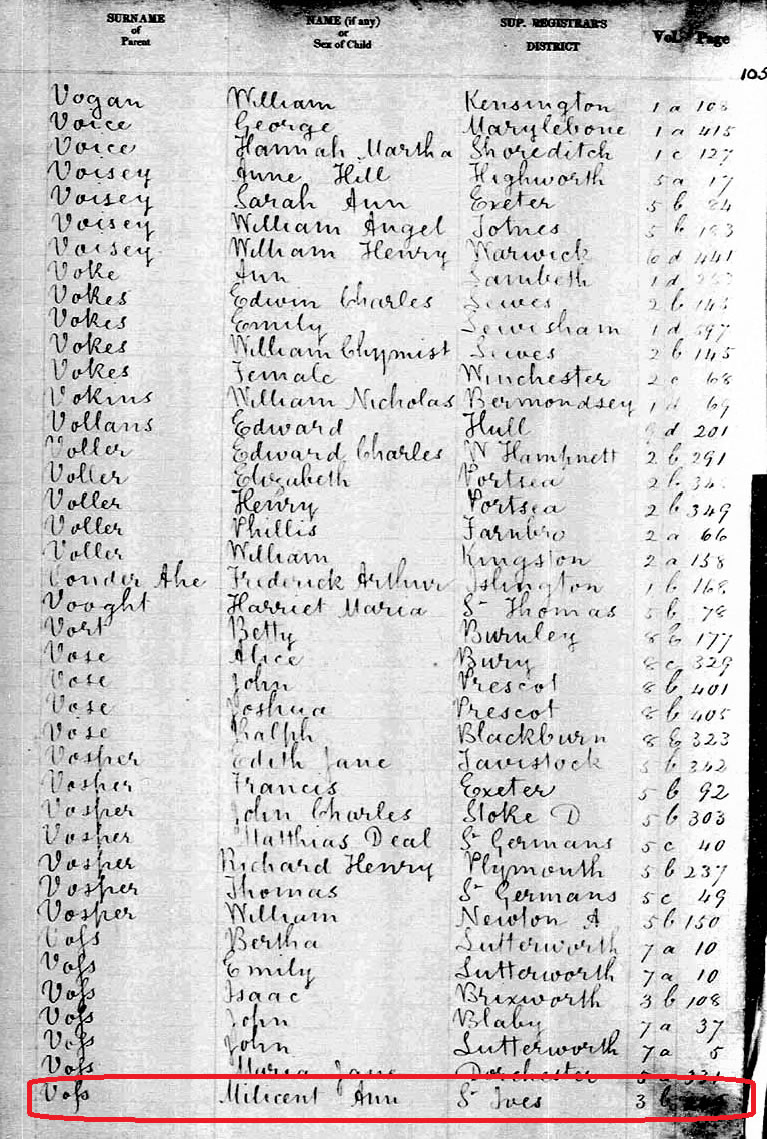

To try and get to the bottom of this Jonnie heads to St Ives in Cambridgeshire where he is able to meet genealogist Gill Blanchard. With her help Jonnie discovers that his 3 x great-grandmother’s name had been Millicent and she was one of four children born to the unmarried Louisa Voss. The next document that Jonnie reads was a witness statement from 1841 that related to a pub having its licence revoked. The statement names Jonnie’s 4x great-grandmother Louisa Voss, plus two other women, as reputed “bad characters of Warboys”. They are accused of drinking, playing loud music late at night in winter and “for.” Gill explains that “for.” is a shortening of the word “fornicating”.

OK, so she was just having a good time? … Well, that doesn’t make you a bad person, does it?

The programme sees Jonnie go on a visit to the small village of Warboys in Cambridgeshire where Louisa Voss had been living in 1841. Meeting with historian Karen Sayer at the Warboys pub that played its part in his ancestor’s story, he sees a police report that hints that the pub in Louisa’s day may have also operated as a brothel. Though there is no evidence that Louisa was tried for soliciting, or even that she was reputed to be a prostitute, it is still possible that she may have occasionally turned to prostitution to scrape a living. With her perceived “bad character” Louisa would have found it difficult to find employment and the historian found out that she ended up working in an agricultural “gang.” These groups of agricultural workers received a fair amount of attention in the newspapers. Women and children toiled in the fields while being supervised by a “ganger” who often brutalised the people working under him to the point where those labouring were thought of as “white slaves”.

Access Over a Billion Records

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

Really it sounds like working in these gangs almost changes these women, you know, it changed possibly Louisa.

The next discovery for Jonnie is that Louisa was found guilty of stealing the equivalent of three bags of potatoes from her ganger. For this she was fined ten shillings approximately 20% of her annual income. To add to her woes she gave birth to a daughter around this time, called Emma. The child tragically died of measles aged just two.

Jonnie meets Dr Samantha Williams at the Huntingdon archives in order to look deeper into Louisa’s story. Jonnie is shown the records of a hearing in which Louisa petitioned to receive maintenance from her former boss, George Fearey, who she alleged was the father of her son, also named George. The account divulges that even in the 19th-century rural community men had most of the power in the workplace and it transpires that Louisa’s former boss appears to have gone on to intimidate the witness who was to appear in court on Louisa’s behalf as she was another woman in the agricultural gang. There does not seem to be any evidence that Louisa received any compensation from George Fearey. In fact the evidence points to the opposite as Louisa, her son George and daughter Millicent then are forced to enter the workhouse on account of Louisa having no employment.

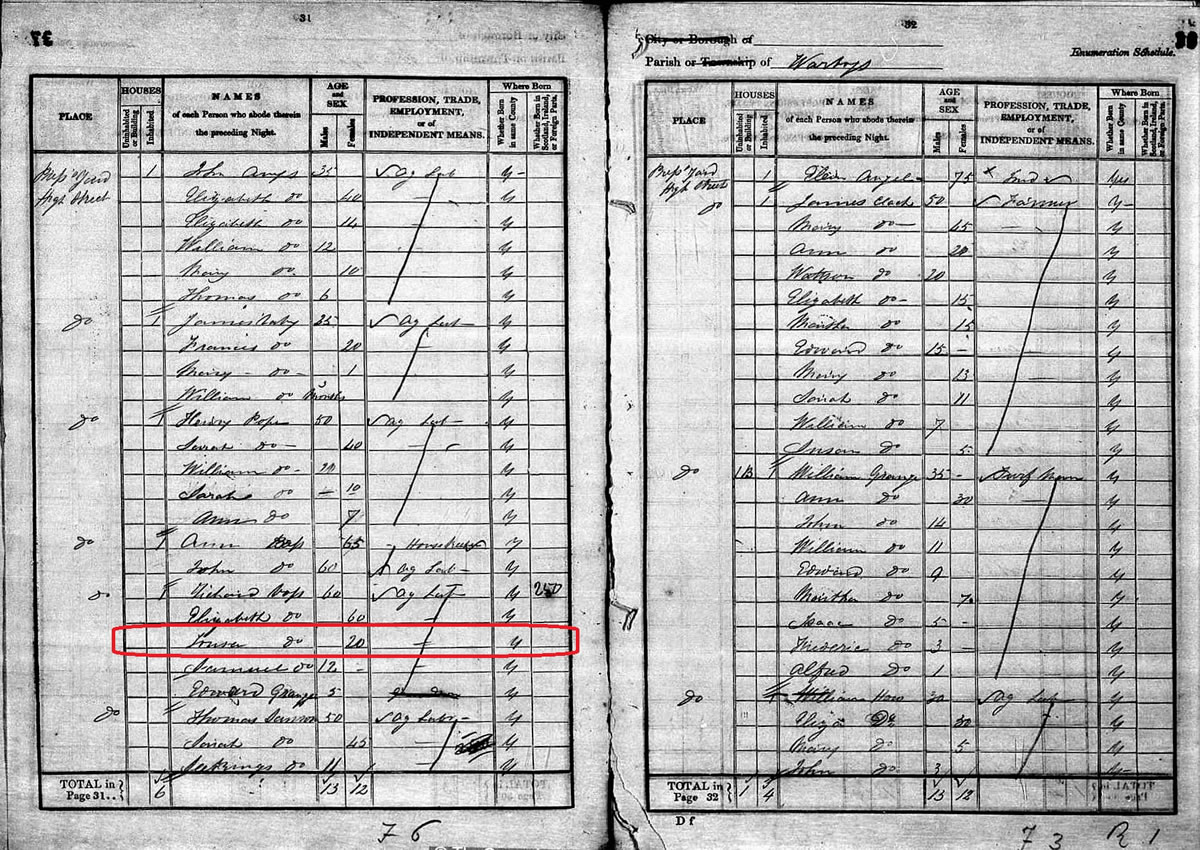

In 1851 Louisa and her son Edward had been living with her elderly parents, as we can see in the 1851 census on TheGenealogist. But Jonnie learns from research in the programme that Louisa had gone into the workhouse from December 1853 to February 1854. A search of TheGenealogist’s birth index records that Millicent was born in the April-June quarter of 1853 so this suggests that their period as inmates of the workhouse would have been after her daughter (Jonnie’s 3x great-grandmother) was born.

To understand more Jonnie meets the workhouse expert Peter Higgingbottom outside the very workhouse, now converted into flats, that Louisa and her children had been inmates of. Despite the harsh conditions of the institution for Louisa, the shelter, meals and bed it provided could have been a welcome respite for an unemployed woman in an agricultural area. Especially so during the winter. There are further records that Jonnie discovers in the genealogy programme that reveal that Louisa had another son, Samuel. She found it necessary to take the alleged father to court for assault just a year after Samuel’s birth.

For me it shows that Louisa is clearly quite a strong, independent woman. She’s not afraid to take somebody to court – this is the second time she’s taken somebody to court that we’ve found – so I think for me this just speaks of her independence, and her fire.

Jonnie is keen to discover what happened to Louisa and the children after they got out of the workhouse. Returning to Warboys he meets up with Dr Nicola Verdon in the local parish church and she shows Jonnie his 3x great-grandmother Millicent Voss’ wedding certificate. In the space for the father’s name, she has simply filled in “illegitimate”. This was unusual as most other women in this situation would have often made up a name to cover their embarrassment.

I guess that really speaks about how she was brought up and how she was raised. She clearly respected her mother a lot.

Millicent’s husband was John Pope who worked as a carter, looking after horses. Later he become an employer himself in Boston, Lancashire and Jonnie’s 4x great-grandmother Louisa moved there to live with Millicent and John. Louisa would eventually die there in 1885. She would have been aged 64 and succumbed to breast cancer.

When I first learned about Louisa having 4 illegitimate children you just think she’s just a young woman who’s just a bit wild. Then you learn more about her and you learn that…she lived a really tough life… And she wasn’t afraid of getting in men’s faces. And back in the 1850s, you know, standing up to men was no mean feat. She was before her time really.

Sources:

Press Information from IJPR on behalf of the programme makers, Wall to Wall Media

Extra research and record images from TheGenealogist.co.uk

Photos from BBC Images