Robert Rinder who was born on the 31st May 1978 in London is a British lawyer who made his name as television’s ‘Judge Rinder’ and, in 2015 was one of the stars appearing on Strictly Come Dancing. Robert is from a large Jewish family and is very close to his 94 year old maternal grandmother Lottie:

She…is still very much at the quiet centre of our family.

It emerges in this programme that Lottie has rarely talked to the family about her father, Robert’s great-grandfather. There are family tales that speak of him being ‘damaged in the war’ but no one knows any more.

Another line of enquiry that Robert wants to pursue in his family history journey is to discover more about Lottie’s husband and his grandfather, Morris Malenicky. Morris had been a Holocaust survivor and has left a profound legacy in Robert’s family.

…when you see documents in black and white – and I’ve always worked in black and white – it gives a concreteness to their truth in a way which I’m slightly nervous about…

Morris died at the age of 78 in London in 2001. Before his passing he was able to register his close family’s deaths in the Holocaust in 1942. Robert had not seen this document before. He reads the shocking details…

‘Malenicky’. Place of birth: ‘Piotrkow, Poland’ … Circumstances of death: ‘four sisters, a ‘brother, parents, Treblinka Camp.’ … ‘gas chambers, crematorium’. Imagine writing that, how your four sisters, your brother and your parents were wiped out.

Although Robert knew the bones of the story of how Morris had survived, there’s still a lot for Robert to find out. He had visited Poland back in 1998 when, as a teenager, he went there with his grandfather Morris. With the research for the Who Do you Think You Are? programme Robert realises that it’s now time for him to return again and confront the family history that he previously wasn’t ready for. He travels to Piotrkow, Poland, his grandfather’s birthplace to begin his quest.

On his arrival Robert finds that the apartment block where Morris grew up is now abandoned. He meets historian Netanel Yecheili who is able to explain to Robert that his family had once owned all the apartments in the block. Not only did Robert’s family rent their flat from Netanel’s family but both their grandfathers were very good friends as children.

Robert gets to view a number of documents that gives an insight into the upbringing of his grandfather and the family that Morris found it too hard to talk about. Reading a list of the children that had previously been in the house, Robert notices that Morris’s birthday was down as the 11th February which, coincidentally, happened to be the day that they were filming that part of the Who Do You Think You Are? programme. It would have been his grandfather’s 95th birthday and Robert was sitting across from the room where Morris had been born.

It transpires that the life the Malinicky family knew here changed profoundly on 1st September 1939 with the start of the Second World War. Five days later German troops marched into Piotrkow and inside a month the Nazis had created the first Jewish ghetto in occupied Europe where they forced the Jews to live.

Documents shown to Robert include a list of all the members of the family and so for the first time he learns the names of his grandfather Morris’s siblings. This is, however, the last record of the family members all together 5 months later they are rounded up and sent to Treblinka to meet their fate. Here all of them, except for Morris, make up part of the horrific statistic of an estimated 6 million Jews who would be systematically murdered by the Nazis during the Second World War. Morris was the only one to survive as the Nazis put him to work in a glass factory in Piotrkow as part of the forced labour used in the German war effort.

Just the most staggering thing that passing on a speeding train – your family gone. And then you go back to your house and you’re alone. I mean. It’s impossible to fathom for my grandfather what that must have been like, to come back to nothing.

The historian Netanel Yecheili takes Robert to visit the ruins of the factory where Morris was forced to work and explains about the conditions of his grandfather’s slave labour. After his time in the glass factory Morris was then sent to Buchenwald in Germany, where after a week he was transported on to its sub-camp at Schlieben.

In the Who Do You Think You Are? episode Robert drives through Germany trying to follow the journey that his grandfather had once made. At the ruins of Schlieben factory Robert meets up with his grandfather’s friend from Piotrkow, Ben Helfgott, who had also ended up as part of the forced workforce at Schlieben. Ben describes how he remembers seeing Morris when he arrived there, and speaks of the starvation that they endured. Robert is moved:

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

This is something so extraordinary to me – that you have the strength to stand on this ground again. It’s something incredibly powerful. Thank you for telling this story – I didn’t know what it was like for him to be here.

In Schlieben Museum, Robert goes deeper into his grandfather’s story with the help of historian Christoph Thonfeld. It emerges that Morris had been transferred to Theresienstadt as the Allied forces advanced towards the German lines. Less than three weeks after Morris arrived at Theresienstadt the camp was liberated by the Russian Army. With the liberation the Red Cross followed and on their arrival they found more than 30,000 malnourished and sick prisoners like Morris.

Amongst the former prisoners of the Germans were hundreds of orphaned children who had nowhere to go on their release. In August 1945, up to 1,000 orphans from Theresienstadt were helped to come to Britain with the aid of a Jewish charity called the Central British Fund. The first group of children were sent to Lake Windermere and this included Robert’s grandfather Morris. As a trained lawyer with his eye for details, Robert immediately notices that Morris’s birth date changes throughout the documents that he is shown. Morris claims to be younger than he was in order to meet the criteria for entry to the UK by the orphans.

Robert next travels to Windermere for the first time and thinks how it would have been for Morris back in 1945.

As I approach Windermere, I imagine what my grandfather Morris would have felt having coming from the dankness and greyness of Schlieben, into this – big sky, and green verdant English loveliness.

In Windermere, Robert meets Harry Spiro who had known his grandfather Morris as a boy in Piotrkow and had come to England from the Theresienstadt camp at the same time as Morris. At a cinema in Windermere they view some footage of the Theresienstadt orphans leaving in August 1945 for their new life in the northwest of England. Harry recognises old friends on the film and describes how unbelievable to him was the moment of arriving in the UK. Carers devoted time to the children to show the new arrivals that life was worth living. Eventually the orphans were able to gradually rebuild their lives, with support of their new-found families.

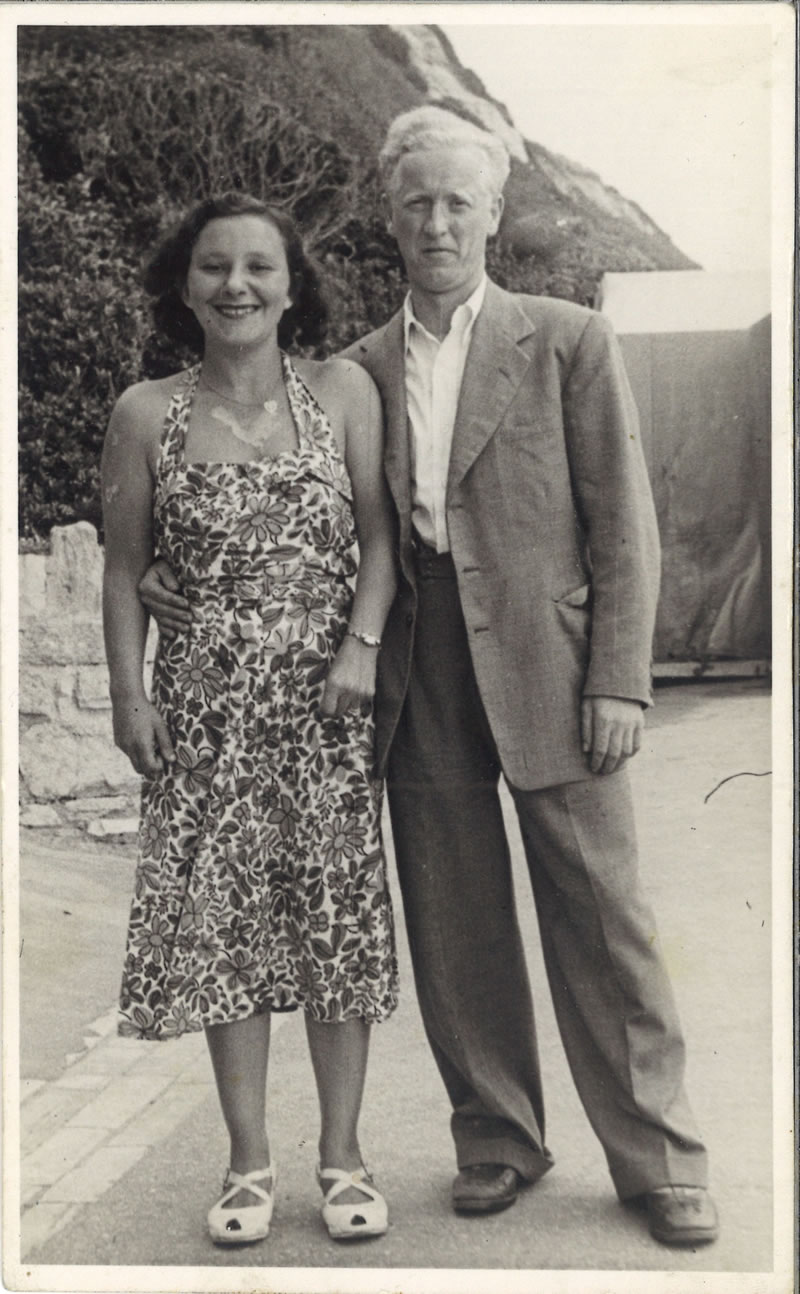

The next part of Robert’s family history trail involves historian Trevor Avery helping Robert to find out about how his grandfather Morris built a new life in Britain after his liberation. Robert is extremely moved to read a letter written by Morris to Oscar Friedmann. Robert’s grandfather was inviting the head of the Windermere Project to his wedding years later. And now, Robert discovers, Morris has admitted his actual age as he settles down in the UK to marry Robert’s grandmother Lottie.

It’s been a real privilege, a real gift, to walk that path with him. And I love this country too, really, and the rule of law, and so much of what I became, I guess, is informed by him.

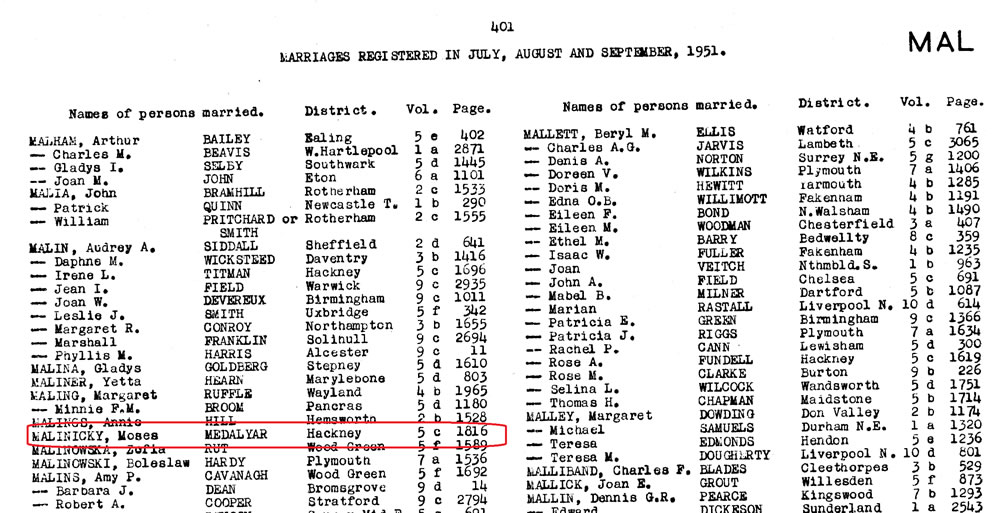

Using TheGenealogist we can find a marriage for the couple in 1951, though Morris is registered as Moses and there are two versions of his surname in the index pages: Malinicky and Malenicky.

Also the naturalisation records on TheGenealogist reveals that Robert’s grandfather became British in 1957 and gives yet another version of his surname, Malinek, under Alias.

Robert’s attention now turns to discovering a mystery surrounding his grandmother Lottie’s father. Robert visits his mother Angela to see if he can find out more. Angela can tell him that Lottie’s father had been named Israel Medalyer and she has a photo of him in army uniform. She has always been under the impression that he had been shell-shocked. Angela is surprised when her son speculates that Israel may have committed suicide. Israel and his wife Kate Silver’s wedding license, or katubah, reveals that their marriage took place in Great Garden Street Synagogue, in the East End of London this is the next place on Robert’s itinerary as he follows in his ancestors’ tracks.

Robert visits the Sandys Row Synagogue where historian Fern Riddell shows him some pertinent records. He discovers from Fern that his great-grandfather’s family were from Talsen, a small town that is now in modern-day Latvia. Robert then sees his great-grandfather’s war record. He is surprised, but also relieved that this document shows that Israel served in a training battalion which never saw active service and would have been stationed at home in England during the First World War.

Access Over a Billion Records

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

Wanting to find out more about his great grandfather Robert then views Israel’s death certificate to see what he can glean from the document. He notes that Israel died from natural causes. But his relief at this quickly turns to unease as he notes the location: Friern Barnet Hospital. As Robert grew up in North London he remembers that this was a mental health institution.

The genealogy programme takes Robert to the site of the Friern Barnet Hospital and it is here that he sees his great grandfather’s case file for the first time. There is a sullen-looking admission photo of his great-grandfather and the information reveals that Israel had been sectioned in 1932. He reads

‘The facts indicating insanity. He is deluded and hallucinated. He states that his neighbours have been persecuting him for years. Has periods of excitement and restlessness. Abusive and threatening towards the staff. He experienced the belief that his wife had lovers.’

Israel Medalyer had been diagnosed as suffering Melancholia today we would label it as Depression. Reading more of the case notes reveals to Robert that his great grandfather had suffered in his youth when he had been separated from his family during a pogrom. The waves of violent hate crimes against Jews and their property occurred across the Russian Empire in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. It would seem that Israel’s resulting symptoms are similar to those that today would be diagnosed as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Israel was to remain a patient at the hospital for many years from 1932 until he died.

To delve further into his ancestor’s roots Robert travels to Riga in Latvia and to the State Historical Archives. He wants to find out more about Israel’s childhood and he discovers here that the family lived on Tukumskaya Street in Talsen, which has been renamed Talsi. The archivist reveals to Robert that the small Latvian town faced a great upheaval in 1905 and his suggestion is that he travel there to find out more.

On the one hand, you don’t really want to know the true extent of it, but on the other, it matters deeply to get a meaningful sense of what it was, what darkness in Israel’s background affected him so gravely later on in life?

It emerges that in 1905 there were a string of revolutionary protests in cities all over Russia. The unrest caught up people who were living even in the quiet rural towns. Even Talsi, where the Medalyers were living, was not an exception.

Visiting the Talsi Regional Museum, Robert is able to examine a map of the events of Talsi during 1905. The government sent in army units to deal with revolutionary activity in the town and as the soldiers approached the city they fired four shots. One of these hit the post office very close to the Medalyer family home.

Robert then reads an account that vividly recounts how the town was burnt by the army and how this struck terror into the civilians. Historian Ilya Lensky informs Robert that while there were no pogroms in Latvia at this time, the violence had been targeted at non-Jews and Jews alike, it still would have been exceedingly traumatic for the teenage Israel.

I feel a sense of almost crushing sadness for him, and for those around him who were also so affected by his mental illness. It’s a story that starts in trauma and ends in abject sadness. There’s a beauty in Latvia, but as I stand here in Talsi, I’m nevertheless haunted by it.

In a Latvia covered in snow, Robert reflects on the different experiences of two men both of whom were important to his grandmother Lottie her husband Morris and her father Israel. Both men came to England and yet the outcome was so different for each:

The reason that I love the country I come from is because of the experiences both these men went through. And it’s a joy and a privilege to think about that, and I guess despite the darkness we’ve been through, I feel like I’ve come through a tunnel. Surprisingly I feel perhaps peculiarly optimistic.

Sources:

Press Information from IJPR on behalf of the programme makers, Wall to Wall Media

Extra research and record images from TheGenealogist.co.uk

Photos from BBC Images