TheGenealogist’s latest release of criminal records in association with The National Archives reveals the far too often circumstances of the poor. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, 10,000 people a year were being imprisoned for debts and many were trapped indefinitely in the prisons as they were not released until their debts were paid in full.

The debtors prison was often a life sentence, with many children being born to inmates whilst incarcerated. The Fleet prison even allowed marriages to be carried out by clergy held in the prison, so inmates and others could avoid the normal charges and banns being read. These records are available to search on TheGenealogist as part of the Non-Conformist record collection.

The prisons gained a reputation for being dirty, overcrowded and prone to outbreaks of disease. Debtors had to provide their own bedding, food and drink, while the wealthier among them used privileges such as ‘Liberty of the Rules’ which allowed them to live within 3 miles outside of the walls of the prison. These fees and privileges were abolished in 1842.

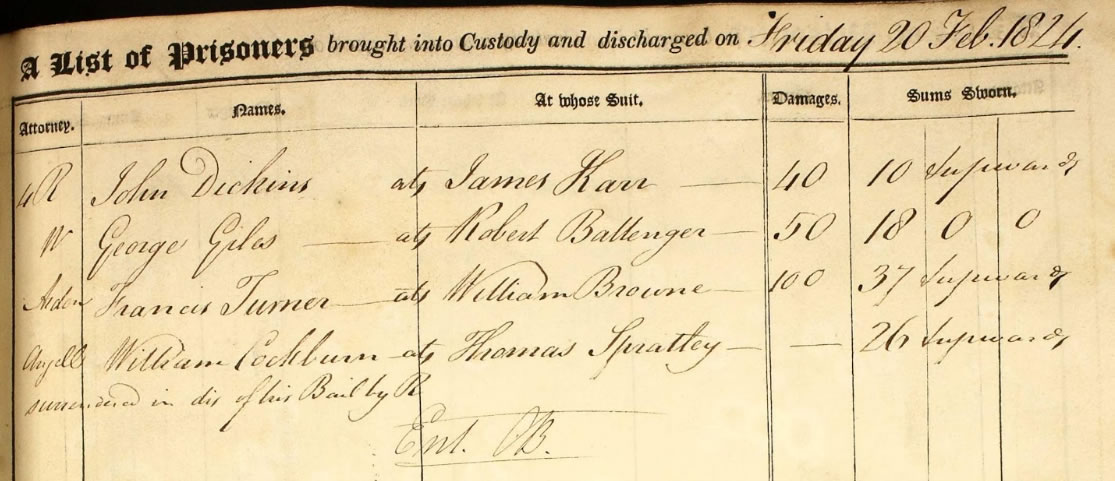

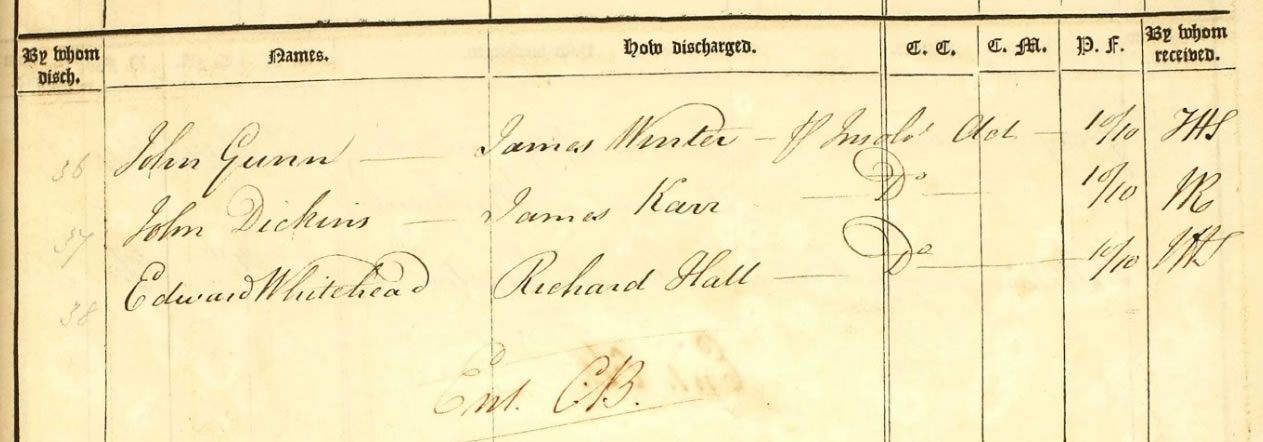

Searching through the newly released PRIS 10 and PRIS 11 records of the King’s Bench Prison, Queen’s and Fleet Prisons and Marshalsea Prison, we find that John Dickens, father of famous author Charles Dickens, was incarcerated in Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison on 20th February 1824. Described by his son Charles as “a jovial opportunist with no money sense”, John owed a baker, James Karr, £40 and 10 shillings. In April 1824, John’s wife Elizabeth joined him in Marshalsea with their four youngest children.

John Dickens’ situation had a profound effect on a 12 year old Charles. To help support the family financially Charles, to his great humiliation, was taken from school to work at Warren’s Blacking Factory. He pasted labels on pots of boot blacking in grim, rat infested conditions, working 10 hours a day for just six shillings a week.

John and his family were released from Marshalsea prison after a few months when his mother died and the inheritance was able to clear his debts.

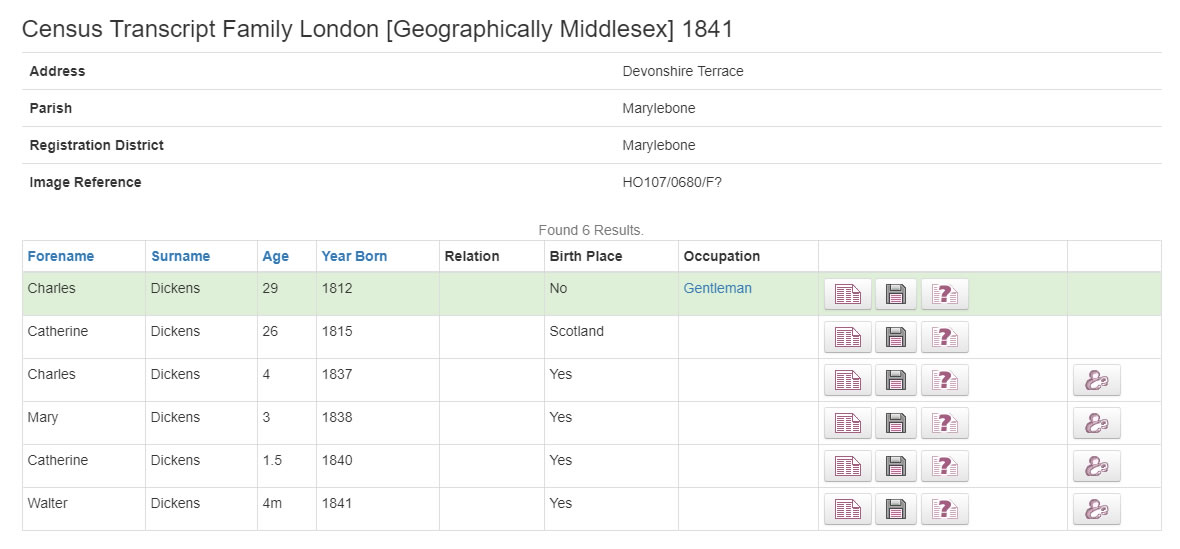

At this time, Charles was still working in the blacking factory under the instruction of his mother, a fact he held in great contempt. After his father was released from prison, his mother did not immediately support his removal from the boot-blacking warehouse. With his father’s support, he managed to go back to school to continue his education, finding work as a junior clerk in May 1827. Charles learnt shorthand in his spare time and then left to become a freelance reporter. He published his first story in a London periodical in 1833 and married Catherine Hogarth in 1836. The couple settled down to family life in London having four children by 1841 as shown by the census.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

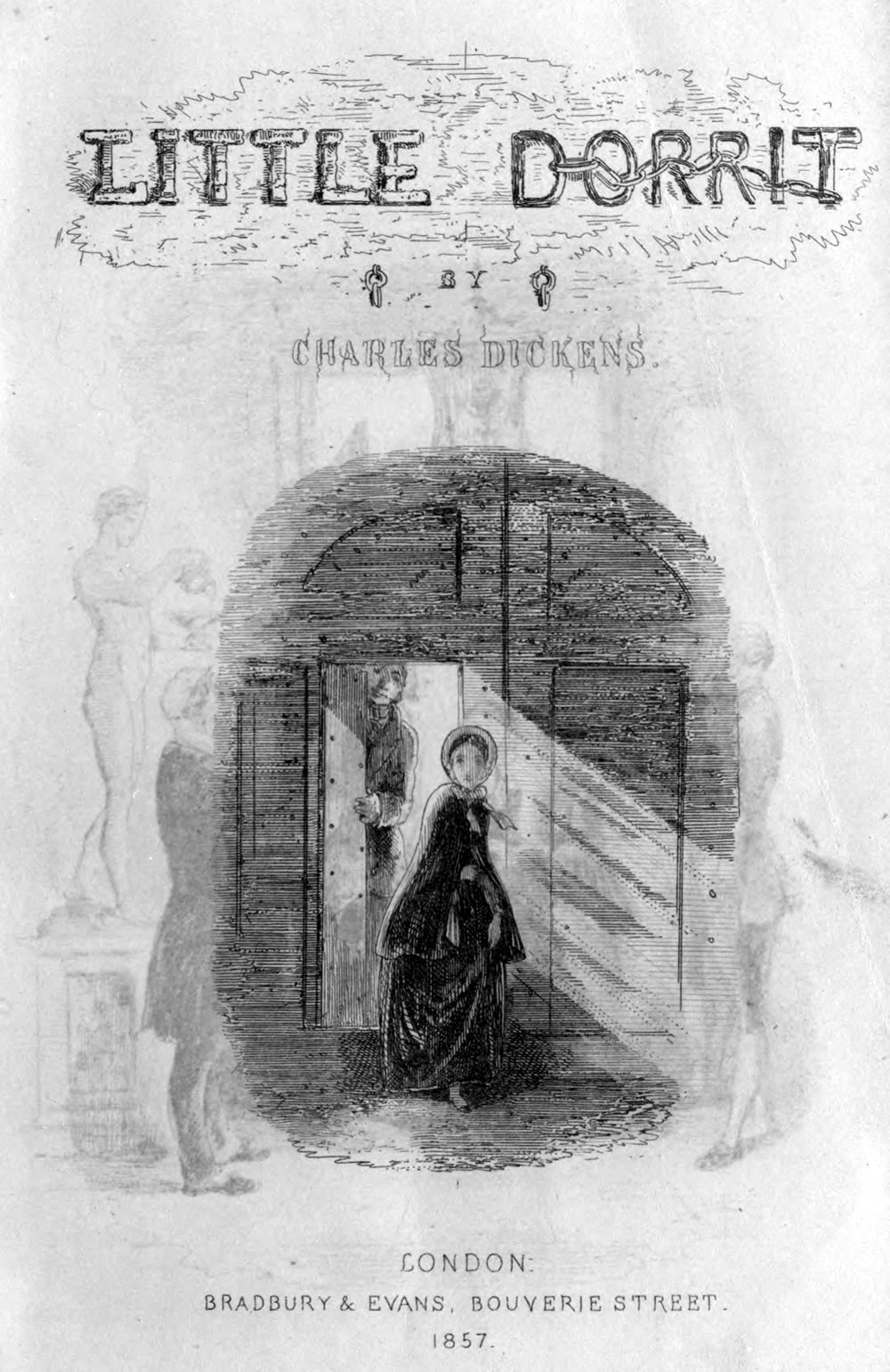

Charles Dickens’ novel Little Dorrit drew on his experience as a child, bringing the harsh realities of life in the debtors prisons to the attention of the general public with Amy Dorrit, the youngest child, born and raised in Marshalsea prison for debtors. Dickens satirised his grievances with the government and society, especially the institution of the debtors prisons. In later years he used his popularity and status to highlight social causes, forcing the Victorians to see the hardships that were being endured by the poor and the disadvantaged. He also helped Great Ormond Street Hospital through its first major financial crisis. Speaking at the hospital’s first annual festival at the St Martin-in-the-Fields Church Hall, he raised enough money for the hospital to purchase a neighbouring house and increase its capacity from 20 beds to 75.

The Marshalsea was closed in 1842 and inmates were relocated to the Bethlem hospital if they were mentally ill, or to the King’s Bench (Queen’s) Prison. Charles Dickens visited what was left of the Marshalsea in May 1857, just before he finished Little Dorrit:

I came to “Marshalsea Place”: the houses in which I recognised, not only as the great block of the former prison, but as preserving the rooms that arose in my mind’s eye when I became Little Dorrit’s biographer … [Marshalsea Place] will look upon the rooms in which the debtors lived; and will stand among the crowding ghosts of many miserable years.