Comedian, writer, presenter and actress Katherine Ryan was born in Canada in June 1983. She has appeared on British panel shows including Mock the Week, Never Mind the Buzzcocks, A League of Their Own, 8 Out of 10 Cats, Would I Lie to You?, QI, Just a Minute, Safeword, and Have I Got News for You.

I was born in Sarnia, Ontario, which I always say sounds like Narnia but with more sandwiches.

Katherine moved to England in 2007 and now lives in London where she’s raising her English-born daughter, Violet. The comedian explains to the viewers of the Who Do You Think You Are? programme that Violet won’t let Katherine forget that she’s Canadian.

Violet is very English and she pulls rank. She’ll correct my Canadian accent all the time. She’ll say ‘I’m so sorry about my mummy: she’s Canadian.’ I just naturally defer to her. It’s the accent.

Katherine is determined to find something in her family background that her daughter Violet will respect and she assumes that if she traces back a little way in her maternal line, she will find English ancestors. The 16th series of the BBC’s genealogy show sets out to help Katherine with this quest and so it deliberately does not look at her paternal line. With regard to her father’s family she explains:

It’s, like, Once Upon a Time, Tipperary, The End. They’re just super Irish and I love them and I know where they came from.

But the search for English ancestry may have some success on her Canadian mother’s side, a branch that she knows very little about before doing this show. Katherine travels to Toronto in Canada to see what her mother can tell her about her own family history.

At her mum’s house the comedian begins by ordering some poutine (a Canadian dish of chips, cheese curds and gravy) to be delivered to the house. Katherine and her mum then get down to looking at a collection of family photos and at a hand drawn family tree that her mum has put together.

Naturally, it features Katherine’s maternal grandmother Dorothy, or Dolly. It is revealed that Dorothy always regretted the way that her family background was much less talked about than that of her husband, Ted’s. The background to this was that Katherine’s grandfather had held some chauvinistic views on women and was a dominant character in the family. Because Dolly’s branch of the family had been overlooked Katherine, who had been close to her grandmother, wants to redress the balance and sets out to research Dorothy’s line. Tracing back a further three generations from Dorothy to Katherine’s great-great-great grandparents she finds out that they were Emma Nicholson and James Arminius Richey. Unusual names are often a gift for family historians and so Katherine is hopeful that, with a name such as James Arminius to search for, that she’ll be able to discover more about her ancestor.

Turning to an online search engine allows Katherine to discover that her 3-times great grandfather was a published author of poetry and still available online today for readers to buy.

…online they just want me to buy his poems. They’re not going to hustle me: I can get it for free in a library.

With this money saving thought in mind, and with a TV crew in tow, Katherine heads to the University of Toronto’s Rare Book Library where she meets with librarian PJ Carefoote. The library has an 1857 edition for Katherine to see and she reads a poem that her ancestor James Arminius Richey wrote for his mother:

But I desponding still must own,

That only downward have I flown,

Have left the bright empyrean day,

To sink in relentless feebleness away.

Katherine jokingly comes to the conclusion that she would have struggled to have understood a word that her 3-times great grandfather had said.

The librarian next produces a number of letters written by James Arminius Richey to his mother when he was younger. In one, that he had written aged eighteen, James peevishly informs his mother that he intends to join the army to go and fight in the Crimean War. He continues by deciding on an amount of money that he considers fair for his father to pay him so that he could buy a commission as an army officer. As James Arminius Richey didn’t join the army it is assumed that his father was not forthcoming with this demand. Katherine is seen in the show to be quite amused by her 3-times great grandfather James’s petulant sign-off:

‘It might seem natural for me to wish to visit you before I depart. The opposite is the case.’ That’s how I feel all the time! …He’s having a really Victorian poetic tantrum here!

The letter, however, gives Katherine a clue to follow up. The letter is addressed to Mrs Richey D.D. the convention of a wife taking her husband’s surname and post-nominal initials points to James’s father being a Doctor of Divinity and the librarian is able to fill in more of the picture revealing that James’s father had been a Methodist minister. When he was older James Arminius Richey also became a minister, though further book research points to him joining the Anglican church and being ordained in that denomination in 1866.*

Katherine is taken to Victoria College, which is also on the University of Toronto’s campus, and it is here that Katherine is able to view for the first time portraits of James Arminius Richey’s parents her 4-times great grandparents the Rev Matthew and Louisa Richey. The reason for the portraits being at the college was because Matthew had been the first principal of the college and a noteworthy person in the Canadian Methodist church at the time.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

They were important people; important enough to have portraits. And that is the kind of high-class ancestry that I’m going for.

Unfortunately for Katherine’s search for ties back to England, however, Katherine’s 4 x great-grandparents lived most of their lives in the now eastern Canadian province of Nova Scotia. Katherine flies next to Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia, in order to continue her search and in the hope of finding out more about Matthew and Louisa and how they came to Canada in the first place.

Katherine then goes to meet historian Renee Rafferty Solani at a church in Toronto’s city centre. This had been the site on which had once stood the Methodist Church in which Katherine’s 4 x great-grandfather Rev Matthew Richey had once preached. A newspaper from the time reported favourably on one of his sermons. This causes Katherine to liken it to present day newspaper critics and comments that her ancestor had “a good review.”

The historian is able to explain that in the mid-19th century, once outside of Halifax itself, Nova Scotia was mostly rural. Preachers like Matthew Richey would have to travel to visit congregations in the rural communities in what were called circuits. These ministers often rode on horseback to the outlying areas and so they were frequently referred to as “saddlebag preachers.” She is shown a contemporary image of an itinerant minister on his horse in the rain holding a brolly for shelter.

I have a horse…useless to me – I don’t ride it to gigs, but I might start.

As Katherine’s 4-times great grandfather’s work would have meant that he would be away from his family for weeks on end, he would have kept in touch with his family by letter. A visit to the Nova Scotia Archives allows Katherine to see a volume there called “Cardiphonia”. Into this book Katherine’s 4-times great grandmother Louisa Richey had created a record of the letters that Matthew had sent her when they were courting. The pages were in her handwriting, neatly copied into the book and revealing Matthew’s words praising Louisa’s virtues grace and modesty but tantalising suggesting that Matthew may have received from Louisa a letter so passionate that she had asked him to destroy it! This causes Katherine to try and understand how women like her ancestor, Louisa, would have been prepared to deal with the realities of physical intimacy ahead of marriage in those times. Katherine finds it hard to see how female relatives could explain it using 19th-century language.

I’m imagining the grandmothers and the mothers using this language to be, like, ‘O hark blessed daughter, on the eve…’ They can’t…they can’t explain it.

The historian’s point of view, in this Who Do You Think You Are? episode, was that what we are dealing with is that intimate domestic conversations between mothers and daughters simply weren’t recorded in documents. Women would have had these exchanges as they were not that different from today’s woman; it is just that women’s voices were not included in the historical records that we have.

Still hoping to find a link to English ancestry Katherine’s hopes are dashed with the Richeys when she reads another letter that had been written to Louisa by Matthew sometime later in their married life. Matthew is writing from “the town that gave me birth” and this turns out to be Donegal, in Ireland. As Louisa was born in New York Katherine realises that this branch of her family tree is not going to bring her any closer to finding the English roots that she craves.

This being the case Katherine now takes a look at another branch on her maternal family tree. Katherine turns to investigating her 5-times great grandparents Giles Hosier and Grace Newell. In the late 1700s they had lived in Bonavista, Newfoundland, Canada’s easternmost province that was synonymous with the cod fishing trade. Bonavista once the nearest harbour for sailing ships crossing the Atlantic from Britain to trade in the fish that was caught around its shore attracted many settlers from the British Isles, including England.

Having travelled to Newfoundland Katherine heads to Bonavista to see the small port where her ancestors had once owned a “fishing room.” This, she discovers, was a type of extra-large shed where the fishermen would land and process their catch. The work for the inhabitants was a very labour intensive process in order to preserve the cod for shipping across the world. The caught fish had to be gutted, salted and dried on platforms called “flakes” and while the cod trade could be lucrative it was also a risky business on account of summer storms and the cold of winter when the fish would have to be taken off the flakes.

Things must have been pretty hard everywhere else for people to purposely want to come here in the snow and fish, and dry fish, and then eat salted fish…I just think they were so tough.

The research has discovered that Katherine’s 5x great-grandparents, Giles and Grace Hosier, had been doing well enough that they had a house in the centre of town, and were bringing up seven children in the community. One of the accounts that mentioned Giles spoke of him being “well educated; a man of refined tastes and superior attainments…” But, “having lived to see his family attain unto young manhood and womanhood, other days and other fortunes came.” With some trepidation Katherine now finds out that Grace and Giles’s 19-year-old son, William, sailed to St. John’s (nowadays the capital of the province) in order to bring back supplies for the family to trade with fishermen over the “fall” or autumn. On his return voyage to Bonavista, his ship was lost and all its cargo and everyone onboard went to the bottom of the sea. Katherine reads a report that states “There was no insurance and the loss spelt ruin to the Hosiers.” The tragic story continues with Giles dying of a broken heart just a few weeks later, followed then by a second son.

Access Over a Billion Records

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

Katherine pays a visit to the local cemetery and finds the headstone commemorating Giles and his sons. But the death notice for Giles at last reveals the connection she was looking for; an ancestor from England. It describes Giles as “of Poole in the county of Dorset, England.” So it is her ill-fated 5x great-grandfather who provides her with a family link to England.

I can take back that story to my daughter, Violet, and say: I’m a little bit English, like you.

Katherine returns to the UK, and then heads for what she now knows is her ancestral home of Poole, Dorset. Her aim is to see how far back she can trace her English ancestry as she has always felt at home in England. She meets up with local historian Dai Watkins at the museum who explains that Giles Hosier was sent to Newfoundland as the agent for one of the big Poole merchants. To Katherine’s delight Dai is able to tell her that Giles came from quite a wealthy family.

Yes! Yes! I really need an inheritance at some point in this. Good.

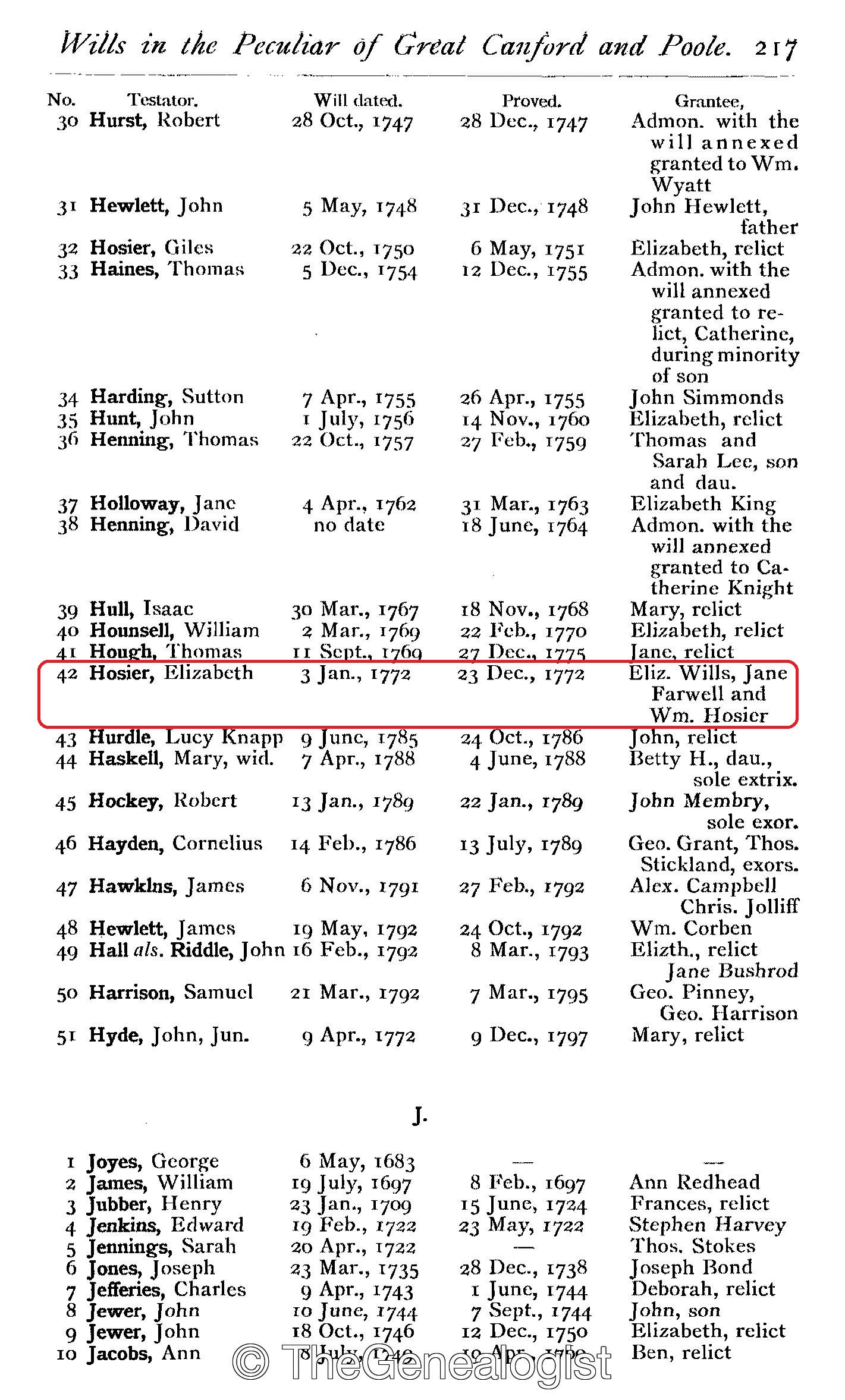

In fact the evidence points to the family having been moderately wealthy. Dai shows Katherine the will of Giles’s grandmother, Elizabeth Hosier Katherine’s seven-times great grandmother who bequeathed just a clock to her grandson.

Using TheGenealogist’s Will records we can see the will was proved in the Peculiar of Great Canford and Poole in 1772.

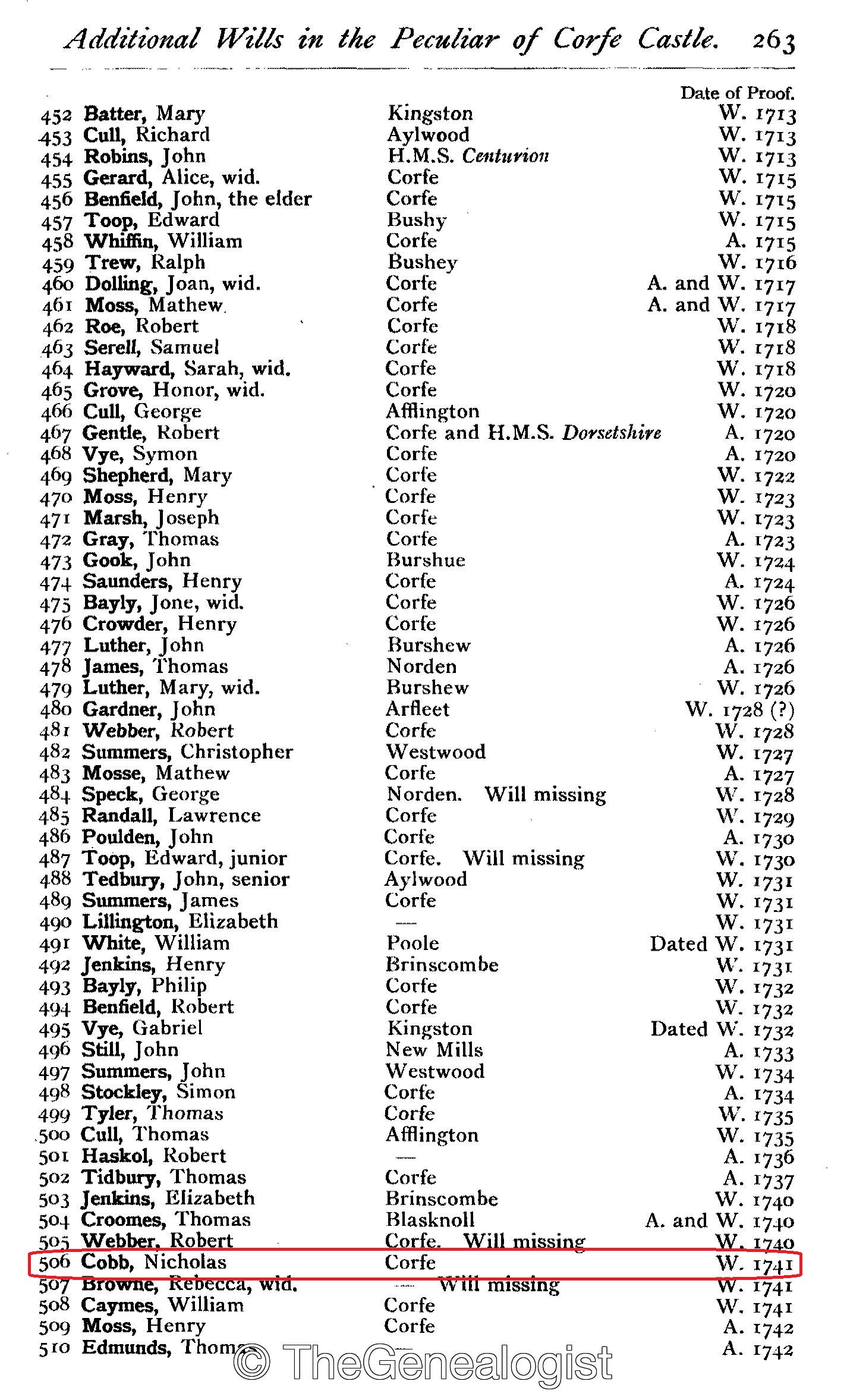

Another will from 1739 this time of Elizabeth’s father (Katherine’s 8x great-grandfather) Nicholas Cobb shows that Cobb came from the village of Corfe Castle but disappointingly for Katherine, he is not from the castle itself.

Katherine goes to visit Corfe Castle with Dai where they head for one of the local pubs. Dai shows Katherine a court document from 1701 which records that Nicholas Cobb was accused of speaking “fraudulous and scurrilous words” about two magistrates in the village.

Slagging people off! This happens to me all the time!

Katherine then discovers that Cobb had also owned brewing equipment at the time of making his will (he leaves a mashing tub to one of his granddaughters) and for a time owned the actual pub that Katherine and Dai are sitting in for the programme in Cobb’s time the tavern had been called the Ship Inn. The historian produces a period map of the village from the middle of the 18th century and this helps to locate “Nicholas Cobb’s house” so-called long after he died. Katherine is then taken across the street to take a look at the cottage that was once her ancestor’s house.

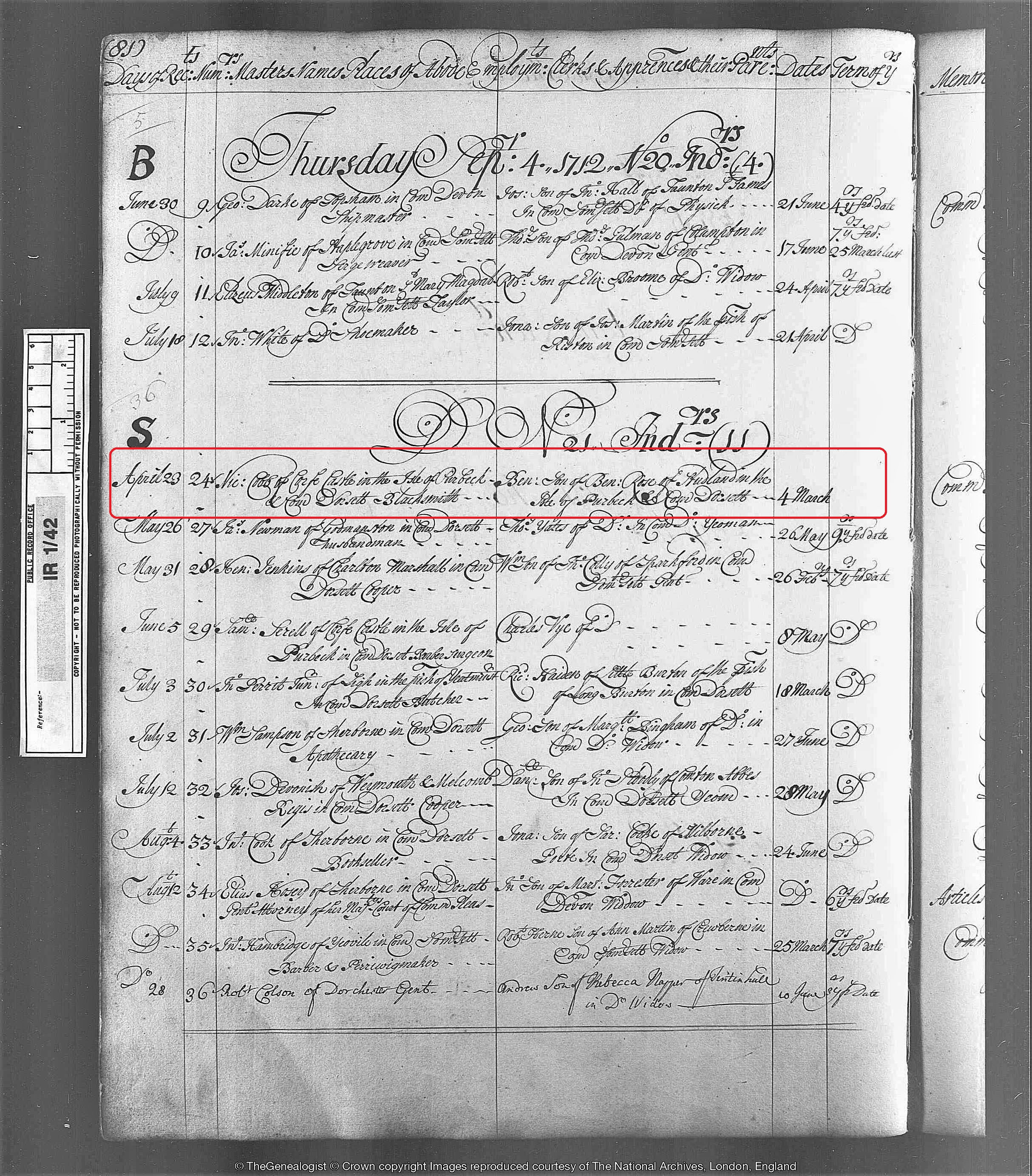

Other records reveal that he was also the local Blacksmith which backs up his will that refers to him as a “Smith”. Using TheGenealogist’s Occupational Records we can see that he is recorded on an Apprenticeship document as the Master who was taking on the apprentice Benjamin Rose in 1712.

My daughter Violet gives me a hard time about not being English. Well now I can tell her I am English – and from a castle no less. She won’t know it’s a village. We won’t tell her.

More seriously, as a teenager and when her grandmother was dying Katherine opted out of visiting her in the hospital. She was also unable, at the time, to say the words that her grandmother had really wanted her to say over the phone. The adult Katherine now sees this exploration of her family history as an “I love you” to her maternal grandmother Dorothy/Dolly. Dorothy had always wanted to talk about her family, and now this is what Katherine has done by taking part in this programme.

Sources:

Press Information from IJPR on behalf of the programme makers Wall to Wall Media Ltd

Extra research and record images from TheGenealogist.co.uk

*The Parish of New London, A History by Thomas Reagh Millman

BBC/Wall to Wall Ltd Images

Wiki Commons