Comedian and Have I Got News For You captain Paul Merton was born in Fulham, South London on 9 July 1957. He is one of two children born to Albert and Mary Ann Martin and although known by his stage name of Paul Merton, his real name is Paul James Martin. Paul was close to both of his late parents, particularly his Irish mum whom he credits with encouraging him along his career path.

That joyful sound of your mother laughing is something that’s sort of stayed with me.

Paul’s mother, Mary Ann Power, had been fostered as a baby in Ireland after her parents had died. The story that Paul had been told was that her father had died at sea. More than that, however, Paul knows very little about his maternal family. It turns out that he knows even less about his English father’s side.

To begin his Who Do You Think You Are? search the cameras follow Paul as he goes to see his sister Angela, who is the keeper of their family’s photo albums.

Looking through the pictures they come across the only photo that they have of their maternal grandfather, James Power. It turns out that Angela knows a bit more of the family story than Paul does. She explains that a priest had once told their maternal grandmother that her husband had drowned at sea; the timing was bad as she was pregnant at the time and the shock caused her to go into premature labour and subsequently she died in childbirth. Looking at death certificates they are able to see that rather than dying at the time of her baby’s birth in fact Julia Power outlived her baby son by a few days.

When you see it written down in black and white…this is a terrible, traumatic experience. Three people dying all within a few days of each other, mother, father, son. I realise now perhaps that’s one of the reasons why my mother didn’t want to tell us about this stuff.

Paul’s Maternal Irish Roots

In his episode from the popular BBC genealogy show, Paul travels to Crooke, County Waterford, Ireland which was where his grandfather James Power had been born in 1889. Paul is interested to discover if the story that his grandfather died at sea was correct, and also find out more about his life. In the village of Passage East Paul is able to talk to a historian who has done some research into James Power.

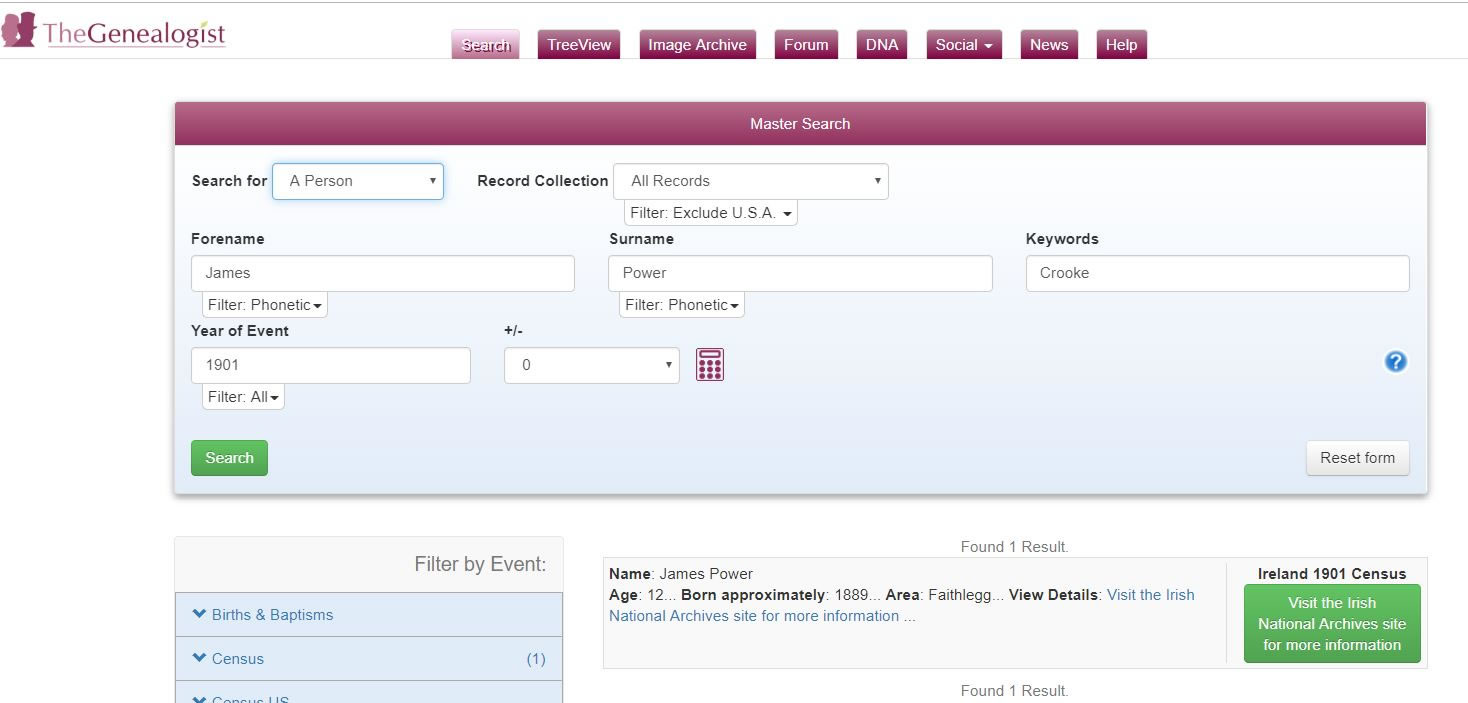

The first document to shed some light is the census return from 1901 which shows that James’s father was a widower and a landless agricultural labourer at the bottom rung of the social ladder. By using TheGenealogist we are able to click a link through to the Irish census on the Irish National Archives site.

Ten years later, aged 22, the next census shows that James had also become a farm labourer following in his father’s footsteps working on the land. From the historian on the programme Paul then learns that in August of the same year as the census, 1911, James had been arrested and found guilty of “riotous behaviour.” James’s life was going in the wrong direction and then came the outbreak of World War One in 1914. Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom and so Irishmen, such as Paul’s grandfather, were encouraged to fight for Ireland as a soldier in the British Army.

The TV programme follows Paul as he heads on to Dublin, where he discovers that his grandfather, James Power, did enlist in the British Army joining the Royal Irish Regiment. The statistics say that approximately 150,000 Irishmen joined up in 1914 and 1915. In total, about 220,000 Irishmen served in the British Military in World War One. It becomes apparent that James Power was not a model recruit, as the first thing Paul is shown is his grandfather’s military Charge Sheet. This lists his offences including one incidence of “highly irregular conduct in barracks” and another of being absent without a pass. Paul realises that his grandfather didn’t seem to like to follow orders and be told what to do…which is not going to go down well in an army.

The research points to James Power going through his training in Dublin during 1916 and this was at the time of the Easter Rising, when Irish Republicans launched a rebellion against being ruled by Britain. The British reacted by mobilising troops onto the streets of Dublin and among them was Paul’s grandfather James Power. Six days of fighting followed in which James’s unit was heavily involved on behalf of the Crown. The result was that the British troops (including Irishmen such as James) had either killed or captured all the rebels. It would have been extremely difficult for the Irish soldiers who would have to follow orders and fire on their fellow countrymen.

He’s enlisted to fight in one battle which is the battle against the Germans…and suddenly here he is on the streets of Dublin shooting at Irishmen.

Once the Easter Rising had been put down, The British authorities held the captured Republican prisoners at Richmond Barracks. Sixteen of the rebels faced the death sentence and were executed. The ruthless punishment by the establishment caused a seachange amongst Irish public opinion and made the rebels into martyrs. What had previously been seen as an unpopular uprising now gained wider support across Ireland.

In the meantime, the Royal Irish Regiment, with Paul’s grandfather among its ranks, were making ready to depart Ireland to fight in the First World War. They made their way to Devenport in England where they embarked on troopships heading overseas. Private James Power would serve in Salonica, Egypt and finally in the Battle of Jerusalem in December of 1917.

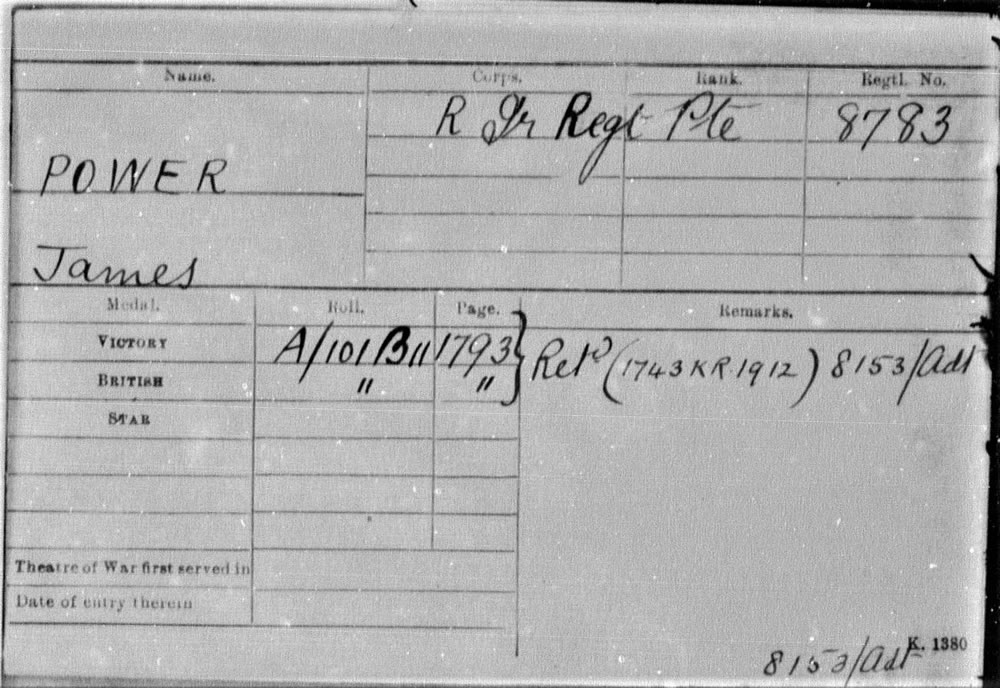

The military historian shows Paul his grandfather’s medal card, which we can see on TheGenealogist by searching its military collections. Paul notes that his grandfather had been awarded the Victory Medal and the British Medal and he wonders what happened to them. The expert explains that the entry he can see in the record under Remarks that reads “Ret’d” means that the medals were returned.

To understand why it was that his grandfather returned the medals that he earned at war, Paul meets with another historian on the genealogy programme. A list reads “Passage East, officers and members of B Company, Third Battalion, East Waterford Brigade from March ‘20 to July ‘21.” “James Power, 1st Lieutenant.”

What is this? He’s in some sort of army again?” Paul reads on: “‘Collecting IRA lorries’ … So he’s a member of the IRA?

The historian explains that James Power had become a member of the old IRA. It was now the early 1920s, and the IRA was the military wing of the Irish Republican movement that was fighting for Ireland’s independence from Britain. The Irish War of Independence was a guerrilla war that began in 1919 when Irish Republicans announced a breakaway government in Dublin. Men such as James Power were recruited into their own rebel army and waged a war against the British. Servicemen who had previously been in the British Army in WWI would often have wanted to prove their Republican credentials to their fellow fighters by returning his British Army medals Paul’s grandfather may have been doing just this. In 1921 a truce was called in the conflict and the next year saw the creation of the Irish Free State when independence was granted to the south of Ireland.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

In search of what happened to James after Ireland gained its independence in the south, Paul goes back to Passage East.

I’m beginning to understand why my mother perhaps didn’t want to find out more details about him…because the more you find out about the man, the more he becomes a real live human being and maybe that’s more difficult to deal with…

In a visit to Crooke Church Paul meets a genealogist. He discovers that this church had been where his grandparents had been married…and also where his mother, Mary Ann, was baptised in 1926. Paul understands that his grandfather, at this stage in his life with a wife and small children, would have needed to find work. But in Ireland, at this time, there were few opportunities to find employment and so the genealogist shows Paul that his grandfather takes a job in Merchant Navy. The employment records, that Paul sees, reveals that James Power became a fireman and trimmer on a ship called the Sheaf Lance that sailed out of Barry in South Wales.

It’s a rather unusual feeling to be looking at the actual font that my mother was baptised in as a two-day-old baby…Looking at the records of James and when he joined the Merchant Navy, this would be certainly the last few months of the whole family being together -- mother, father, the two sisters. Maybe it was the last time there was a family gathering with everybody there.

It’s quite poignant to come back here and to feel a stronger connection to my Irish grandfather who I never met … I sometimes feel that when I’m in Ireland I feel Irish in a way that when I’m in England I don’t particularly feel English. So this has only just helped to enhance my understanding and my appreciation of my Irish roots.

To follow up what had happened to James Power after he left his young family to join the Merchant Navy in South Wales, Paul goes to Cardiff and meets up with a maritime historian. He learns that the Sheaf Lance was a steamship, so the job as a fireman and trimmer was to throw the coal into the furnaces. It was hard, hot, filthy work four hours on, four hours off round the clock.

Going back to the photograph I’ve seen of him, I realise now that I think he’s absolutely knackered. I think that’s probably what it is.

Paul looks at some records for the Sheaf Lance. His Grandfather had been on a voyage that left Barry in December 1926, loaded with coal and destined for Brazil and Argentina. Its return passage brought it back to Wales, arriving back at Penarth near Cardiff on the 5th of April, 1927. James Power left the ship that day, and he is not recorded as sailing on any other voyages.

I thought this was the one bit that I knew for certain, that he died at sea. But apparently not.

To try and sort out this confusion Paul heads to the Glamorganshire Archives in Cardiff to see what its local records contained. Here he is presented with a copy of his grandfather’s death certificate which records that at the age of 37, James Power was found dead in the Glamorganshire Canal in Cardiff on the 19th April, 1927. He had died from “shock from distended stomach acting on diseased heart.” This runs counter to the accepted family story and means that Paul’s grandfather not only didn’t die at sea but also that he didn’t die by drowning! He was probably already dead perhaps from a heart attack by the time he had fallen into the Welsh canal. The archivist explains to Paul that the inquest would have noted if James had been drunk and so it points to him being sober when he died. Wondering about how they identified the mariner, it turns out that a local shopkeeper, who had sold several items to James, was able to identify him. Paul reads: “‘I identified him particularly by his ginger moustache.’“

Paul becomes aware now that his grandfather is buried in Cardiff, a fact that he doesn’t think his mother ever knew as it was never mentioned. There’s no headstone on the grave, but Paul does go to the plot of the unmarked grave in Cathays cemetery, one of the main cemeteries for Cardiff.

I think the appropriate thing to do would be to install a headstone. I’ll speak to the rest of the family about it

A few days ago I knew very little about James. I had a photograph. And I have got to know him over the last few days. Even though I never met him you get to know a person – the man – through his actions, his deeds. And he certainly saw a lot of the world in his short span of time, and played a part in very momentous parts of Irish history.

My thoughts have fluctuated over the last few days about whether my mother would have wanted to have known more about her father. And I’ve now come to the conclusion that actually if there was a place she could have come to, to lay flowers, she would have wanted that.

It’s 92 years ago this happened. I’m the first member of the family to find out his final resting place. That is rather remarkable, isn’t it? It’s a long time ago 1927, and it’s taken this long for us to…find out the truth.

Paul’s Paternal line

Paul returns to London in the BBC’s TV genealogy show as he now wants to pursue the research into his Dad’s side of the family, which he knows very little about. To begin with he starts with his paternal grandmother Elizabeth. Paul has a photograph of her, unsmiling and poker-faced. This does not reflect what he had always been told about her, that she actually had a good sense of humour. He concludes that it was the staging of the photograph that was at fault.

This was the time when nobody was allowed to smile in photographs because life wasn’t that funny.

For this part of the quest Paul pays a visit to the Borough of Southwark in South London, where his paternal grandparents once lived. He meets up with Laura Berry, a professional genealogist who has compiled a family tree from him. The tree traces back several generations from Paul’s grandmother, and the expert draws his attention to his three-times-great grandfather William Simmonds. This ancestor had died in 1886 and his occupation was listed as “musician.” William Simmonds’ son Paul’s great-great grandfather was also called William Simmonds, and on his marriage record he’s also listed as a musician. William Junior married Paul’s great-great grandmother Caroline Plunkett, who was just 17 years old in 1870.

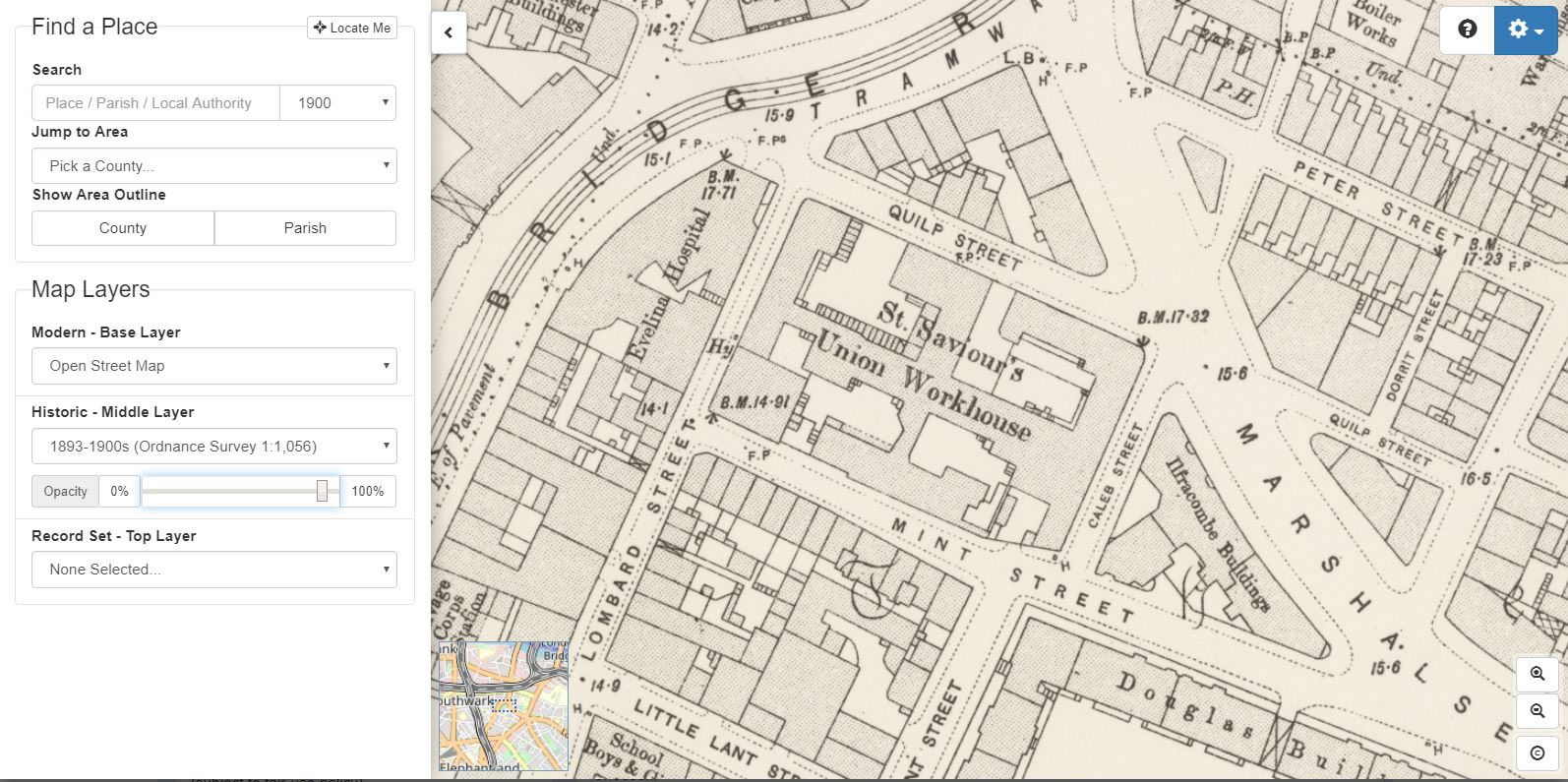

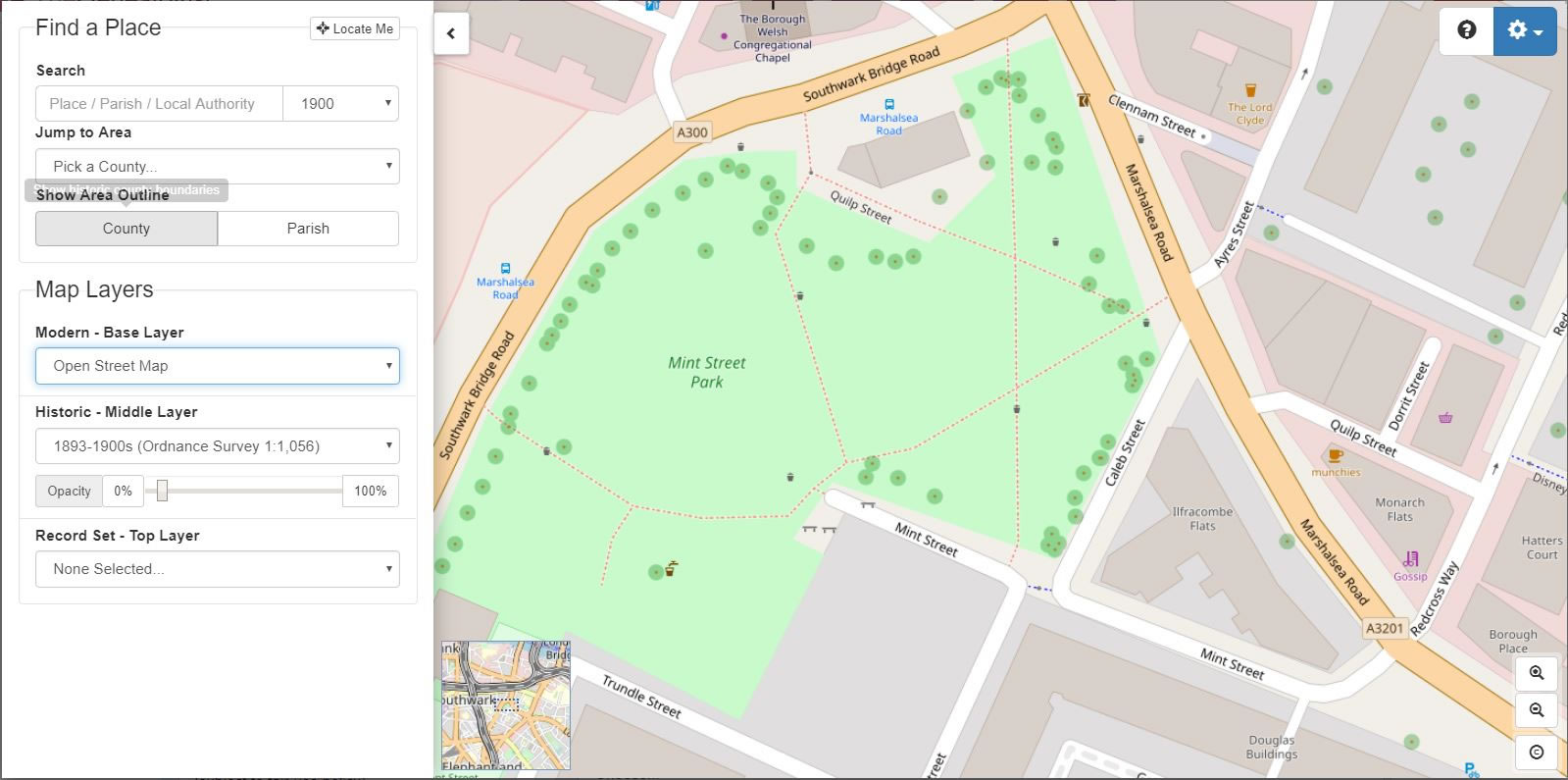

While the occupations of female ancestors are rarely listed on marriage records at this time, another document that Laura Berry has found gives an insight into Caroline especially as it is from a few months before she and William Jr got married. It’s an Admission Register for the Mint Street Workhouse in Southwark one of the workhouses thought to have inspired Charles Dickens to write Oliver Twist. By using TheGenealogist’s Map Explorer we can see where it was once located. Sliding the opacity control on the Map Explorer reveals a modern street map that shows us that the workhouse is long gone to be replaced by the green space of Mint Street Park at the top of the Marshalsea Road, Southwark.

In these times it was often the case that poor women, like Paul’s great-great grandmother Caroline, would use their local workhouse as a maternity hospital. Here, Caroline Plunket gave birth to a child which is thought to have died as an infant. A year on and she had another child called William but what Laura, the professional genealogist, had found out in the record of the first child was that Caroline gave her profession at the time as “vocalist.”

Access Over a Billion Records

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

It’s intriguing that nearly 150 years ago there was somebody in my family who was a performer. Or two people. Musician and vocalist. So the further I go back do you think I’d be related to Beethoven?

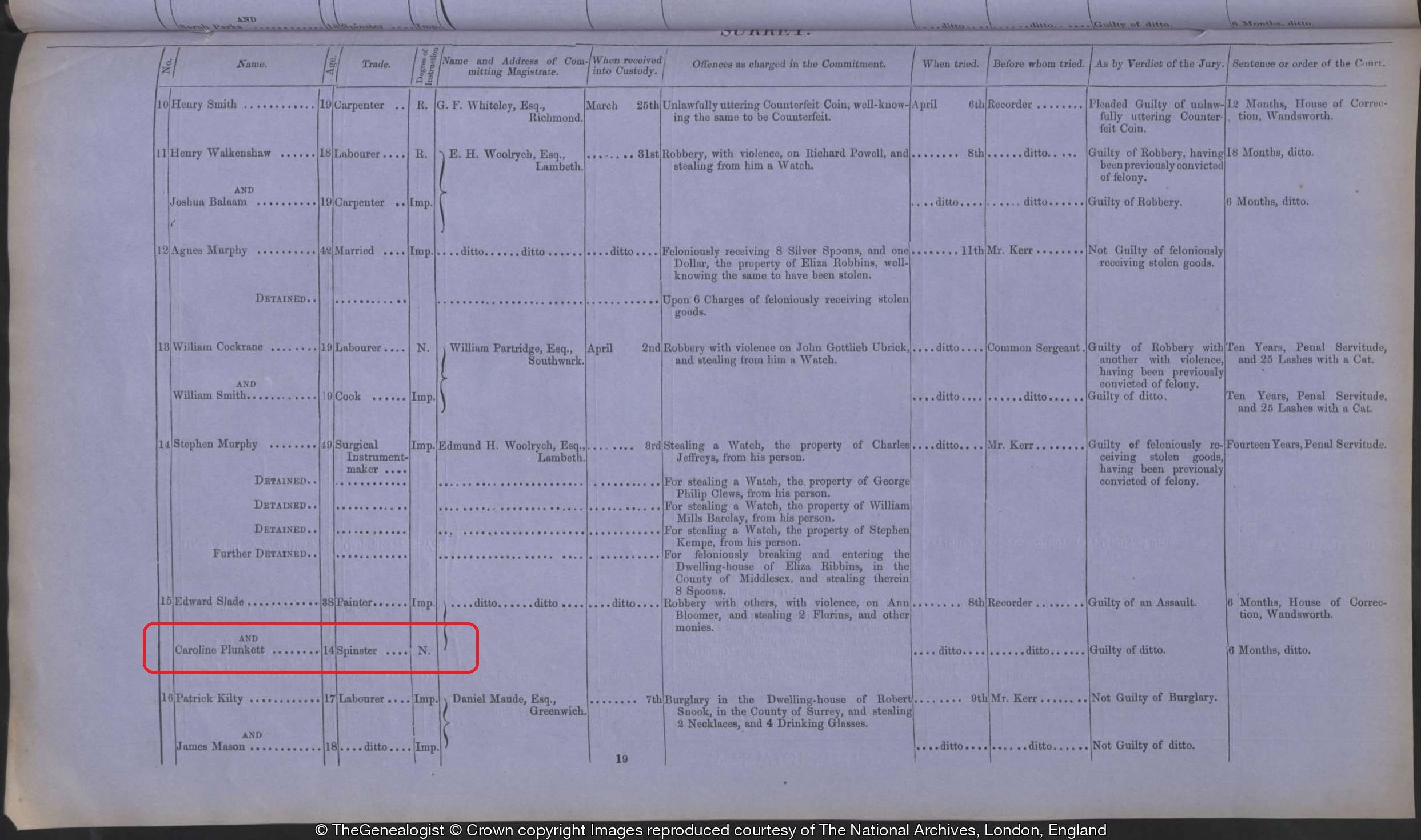

Interested in what he can discover about the musical performances given by his great-great grandparents, Paul is able to meet a music historian who explains that “vocalist” was a fairly new term in the 1870s and that Caroline had been an early example of what we would call a busker today. Researching further for Caroline Plunkett discovers her listed in a proceeding from the Old Bailey in 1867, at this time she had been 14 or 15 years old.

Paul reads the report:

“‘Robbery on Ann Bloomer and stealing a pocket handkerchief and six shillings and sixpence. Henry Bloomer …’ Presumably the husband of Ann Bloomer, says: ‘I am a labourer of Hamilton Road, Norwood. On Saturday night, 22nd March, between 12 and 1 o’clock, my wife and I were going home when three men and a woman stopped us. And the prisoner asked me what I wanted with a woman? I said she is my wife. He then knocked her down with his banjo. I asked him what he meant by it, then he knocked me down. The young woman pitched into my missus and scratched her. I cried for help and the policeman came and took the two prisoners. I heard one of them say: ‘Knock ‘em down, they’ve got plenty of money.’ And in Plunkett’s defence, the only time that Caroline Plunkett says anything, she says: ‘I didn’t touch the woman.’“

The report, that Paul had been given to read in the programme, mentions a banjo being used as a weapon. They decide it is unlikely that a musician would risk damaging an instrument that they played, as it would impact on their ability to do further performances and so obtain money. What it does do is provide a pointer towards the type of music that Caroline and her associates might have been playing. By this time it would have been twenty years into the banjo craze that had come over to Britain from America. Paul takes a look at a typical song that would most likely have been in his great-great grandmother’s repertoire “Buffalo Girls”

Society at this time did not see street musicians as being trustworthy they were regarded with some suspicion. The Who Do You Think You Are? historian points out that for someone like Caroline, who is illiterate and living at the margins, will not leave many records of her own. In cases like this then criminal records are the place to go. As we can see by turning to the Court and Criminal records on TheGenealogist. Here we are able to note that Caroline Plunkett is recorded in the Central Criminal Court: After Trial Calendar of Prisoners, 1868, where she has been sentenced to 6 months in the House of Corrections at Wandsworth.

As Caroline was found guilty and sentenced to six months in Wandsworth prison, that is the next stop for Paul.

This is not my first time in Wandsworth Prison. The first time I came in here was about 1980. I was working with the Civil Service at the time. Nobody told me about this, but I was smoking, rolling tobacco, I could see the way the prisoner kept eyeing the tobacco so I said: ‘Oh well, you know, help yourself, have one.’ ‘Oh thanks very much.’ Next week I came in there was 27 people waiting to see me, and none of them had any idea what training course they wanted to do at all, it was just that word had got around that there was young civil servant who didn’t know the rules about bringing in roll-up tobacco.

Paul is able to have a meeting with the curator of the prison’s museum. In his consultation with this expert it is explained that when Caroline was committed to Wandsworth prison that the prisoners were made to cover their faces. Male prisoners were given a cloth mask to wear over their faces with eye and nose holes cut out. Female prisoners, on the other hand, were forced to wear a veil which allowed them to see out, but prevented others from seeing what they looked like. This was all part of the prison’s separate and silent system; a type of solitary confinement that was applicable for all prisoners at all times and different from solitary confinement being employed as a special punishment. The aim of this was that prisoners were unable to identify each other and the thinking was that the prisoner was meant to reflect on their crimes in total isolation. In order to apply this system to the inmates Wandsworth Prison had been purpose-built in1851 with small, single-occupancy cells. Prisoners were allowed only an hour a day exercise in the open air, when they walked in single file with five or six paces separating each prisoner to make it as difficult as possible for them to communicate with each other.

There was one time a week when they could use their voice and that was at the Sunday church service. As a singer, Caroline probably looked forward to this opportunity even though the prisoners were still kept separate from one another in stalls, even though they would sing as a congregation. By changing the words that they sang, from the original, prisoners could sometimes find a way to talk to each other under the hymns.

Paul sings: “Onward Christian soldiers, we’re breaking out tonight. Meet you by the…”

As a Victorian prison, that is still in use today, the permission of the Governor for Paul to see inside a cell allows him to understand the size of space similar to that which his great-great-grandmother was held in for most of the time. Caroline Plunkett was released from Wandsworth Prison in October 1868 and the records show that two years later she married William Simmonds, Paul’s great-great-grandfather and a musician.

It is extraordinary that such a young person goes through this huge contrast in life. She didn’t let that define her…She lived to be 64, which was a good age at that time. It’s a remarkable life.

It’s great to learn that there’s a performance gene somewhere back in my deep past and I wasn’t the first one to embarrass myself publicly.

Our family never really had a treasure trove of stories, but now there’s quite a few.

When I think about my grandfather – my Mum’s dad, James – going from a man who was almost anonymous and whose ending was completely obscured …we now have uncovered the truth of it and he’s gonna become kind of sort of famous which is sort of … would be mind boggling for him I’m sure.

Some people believe that when you die the spirits of your family come to greet you and if they do at least I’ll recognise him and be able to have a bit of a chat. Whereas beforehand I wouldn’t have had much to say.

Sources:

Press Information from IJPR on behalf of the programme makers Wall to Wall Media Ltd

Extra research and record images from TheGenealogist.co.uk

BBC/Wall to Wall Ltd Images