Sharon Osbourne, well known on both sides of the Atlantic, divides her time between her homes in Los Angeles, USA where she lives with her larger than life rock star husband Ozzy Osbourne and England, where both she and Ozzy were born. Sharon is eager to find out about her family history in the country where she grew up.

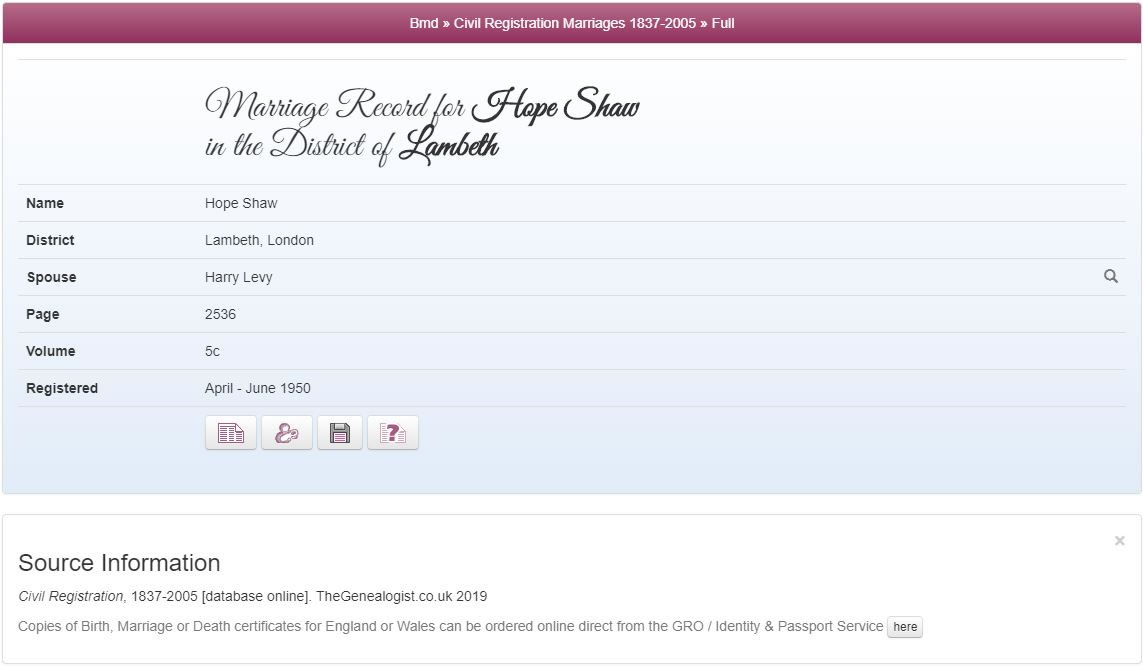

Sharon Rachel Levy was born in Brixton in 1952 to Hope Shaw, a dancer, and Don Arden, a music agent who set up his own record label. Don, whose birth name was Harry Levy, Sharon acknowledges had been ambitious and a workaholic. In the Who Do You Think You Are? TV episode broadcast by the BBC on 4 September 2019, Sharon remembers her childhood as one where both she and her brother could run wild. They had a whole lot of freedom to do as they liked with no structure imposed by their parents. While a lot is left unsaid about her relationships with her parents in this programme, Sharon does state that she believes that she has inherited a work ethic from her parents. After leaving school Sharon joined her father in the music business and it is well documented elsewhere that while managing Black Sabbath, he sacked Ozzy Osbourne. Sharon split from her father and took over managing Ozzy.

Sharon knows her father’s family roots are in Manchester’s Jewish community. What she wants to discover more about is her mother’s side of the family, which she has always believed was Irish. The small amount that she does know about her maternal line is that her grandmother on that side, Doris who was usually known as Dolly, had been a choreographer/dancer working in Vaudeville. The young Sharon had found her grandmother frightening with lots of white hair and red lipstick so that Sharon thought she was a witch. As for her maternal grandfather, he is a complete mystery to her. It turns out that Sharon doesn’t even know his name as Dolly never spoke about him. Sharon is excited to discover what she can and to find out “how it all started”.

Probably I come from a load of old witches that were burnt at the stake or something – that would be fabulous!

Discovering her Maternal Line

To begin her journey Sharon meets up with her niece, Gina, who has always taken an interest in the family’s history. On Gina’s visit to Sharon she has brought with her some family memorabilia, this includes a photo of Sharon’s mother, Hope, wearing her stage costume and dated on the back as being Southampton in 1935. “I definitely got her legs,“ laughs Sharon, “Thanks a lot Hope”.

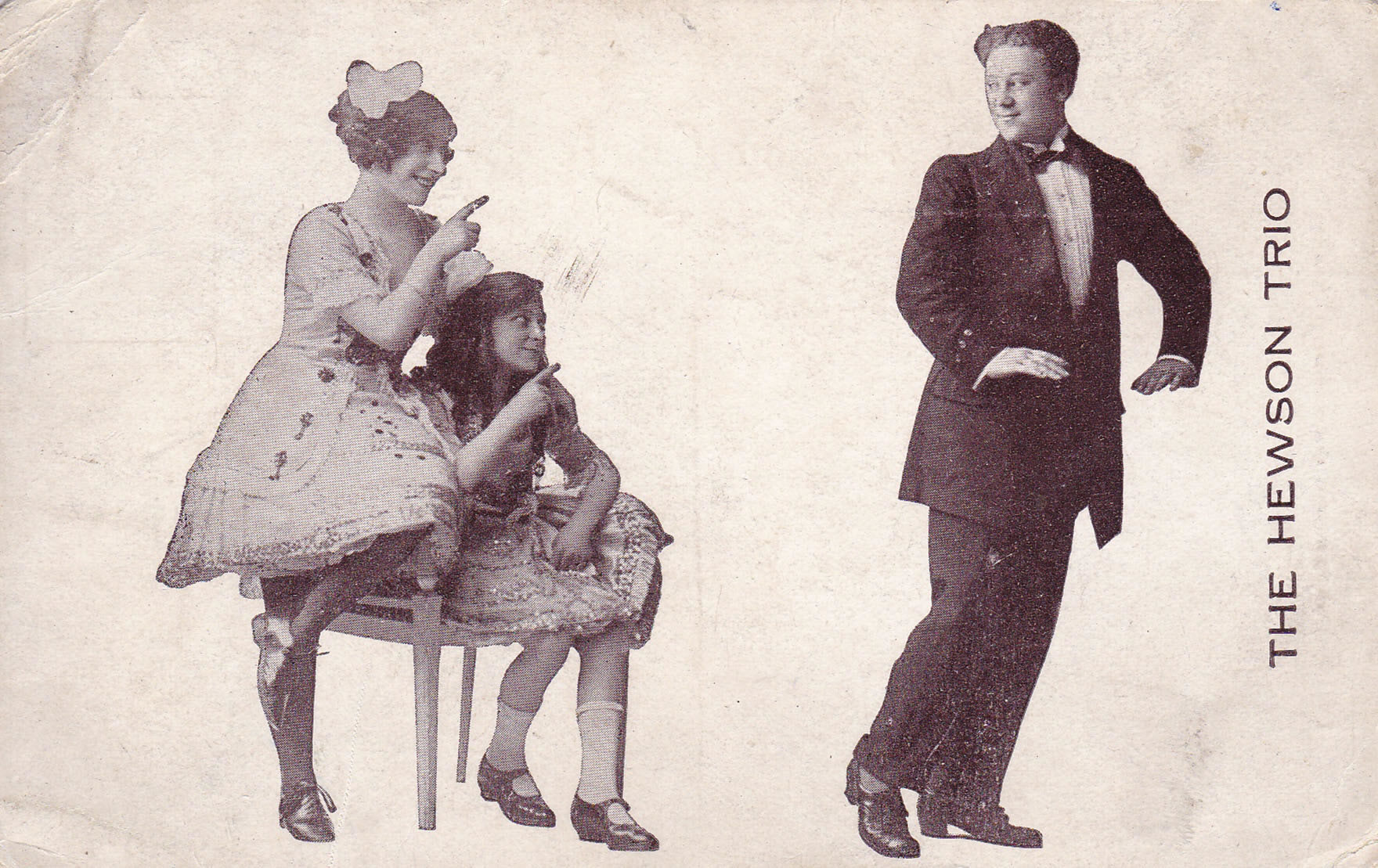

In another photograph promoting a performance, Sharon sees her grandmother Dolly as a young woman. In the image there is also a man and Gina reveals that this is Sharon’s grandfather, Arthur James Shaw (who had been known as James). This is the first time that Sharon has ever seen a picture of her grandfather, or even heard his name. Studying the photograph causes Sharon to muse: “What did you get up to Mister?”

In the picture, alongside James and Dolly, there is another person whom they think may have been Dolly’s sister Ira. All three of them are dressed in costume for a Vaudeville performance. Sharon had not even known that Dolly had a sister and she wonders what ever happened to her great-aunt Ira. Gina is able to tell Sharon that their ancestors had collectively performed under the name of the ‘Hewson Trio’. Gina has a copy of The Stage newspaper from 1912, to show Sharon. In this publication the Hewsons advertise themselves as one of “the greatest novelty, vocal and dance acts in Vaudeville”. Sharon is intrigued as to what the novelty was to the act. In the picture that Gina had turned up, they appear to be doing some sort of a comedy turn, with the two women shaking their fingers at James in a disapproving way. The trio had probably had to travel around the country to perform “fun, but no sense of home. No sense of family…of security”, Sharon observes seeing that their lives on the road would have been comparable to her own childhood with her parents always coming and going. James and Dolly’s marriage certificate reveals that they married in 1915; just a year into the First World War.

Did you go into the War? What happened to you Mister?

Sharon is pleased to find that her suspicions about James have been proven wrong.

You know, I go right to the edge; it’s like ‘right! She was never married!’ And here she is with her husband, my grandfather. But I’d still like to know what actually happened to him and why nobody ever spoke of him.

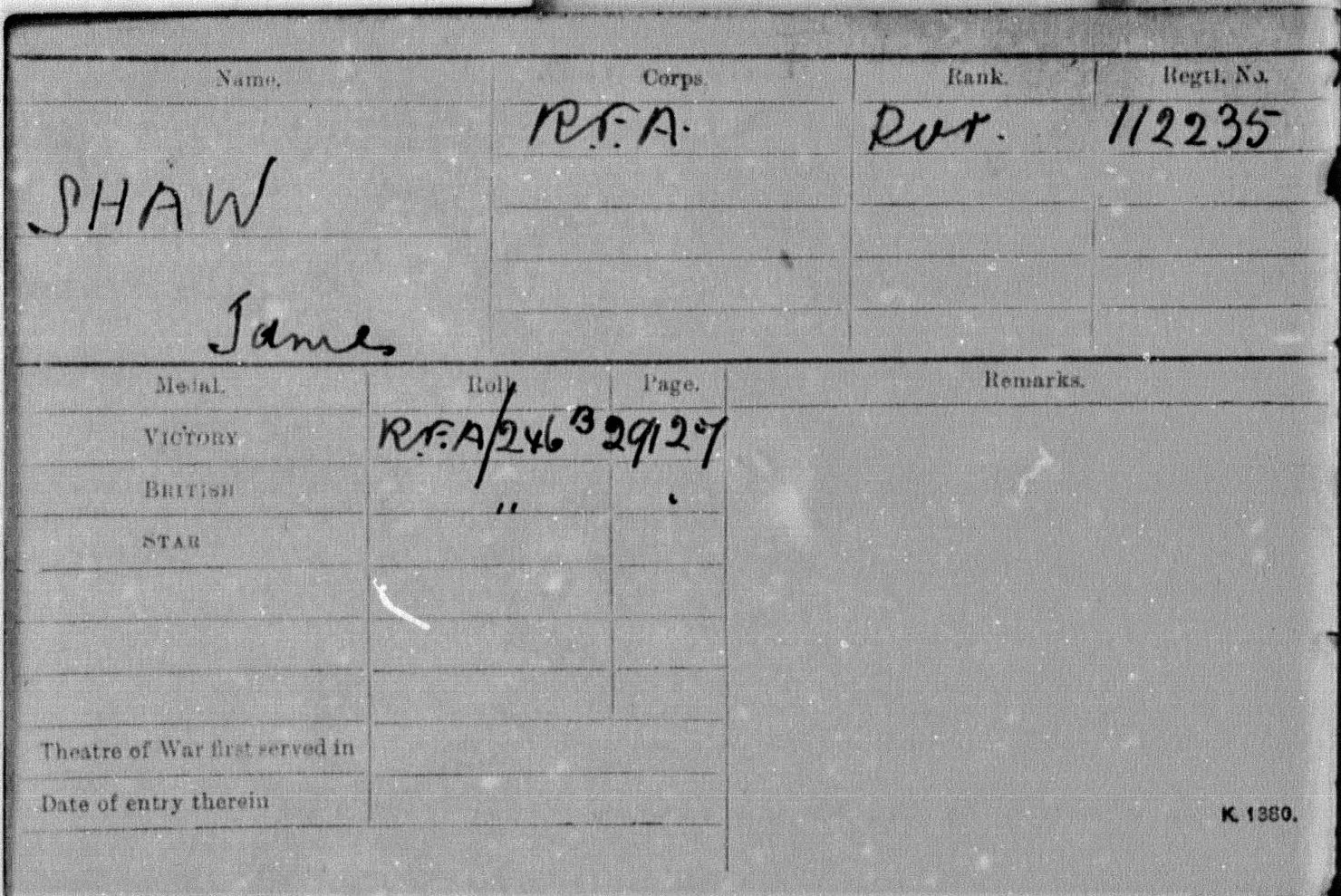

Sharon goes online to search for the British Army service records which reveal to her that James had enlisted into the Royal Artillery as a ‘driver’ in October 1915 with the regimental number of 112235. He was aged 27 when he joined up and the army documented that his profession was as a ‘music hall artist’. At this time he had only been married to Dolly for a few months and it was just one month before Sharon’s mother, Hope, was born that James and his comrades were sent across the Mediterranean to the Egypt theatre of war. The records Sharon sees indicated that he only returned home three years later in 1919. From a search of the Military records on TheGenealogist we can find his medal card that identifies his entitlement to the Victory and British medal.

Sharon is interested in how Dolly would have coped with her husband gone for so long “It must have been very hard just to get by every week”. Sharon has the suspicion that Dolly and her sister Ira must have kept working to make a living.

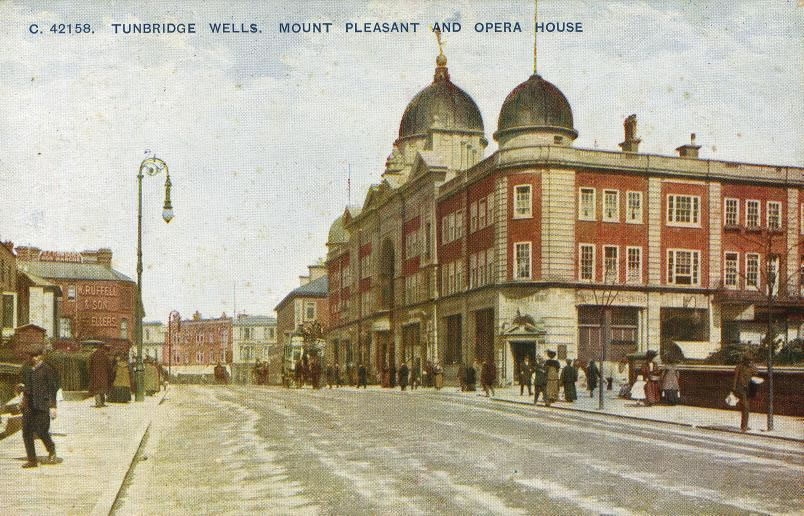

By the time of the First World War, what had been called Music Hall had now become known as Variety theatre. The audience would go to see featured acts like singers, acrobats, jugglers and dancers and new theatres were springing up all over Britain at this time to accommodate the new popular entertainment. The genealogy television show follows Sharon as she meets a historian in one of the few preserved venues from that period, the Opera House in Tunbridge Wells. The building has been given a new lease of life today as a pub, with much of the original theatre features retained. By searching TheGenealogist’s Image Archives we can find a historic picture of the venue on Mount Pleasant Road.

It was at this theatre that, just over 100 years ago at Christmas time in 1917, Dolly and Ira were on the bill. No longer performing as The Hewson Trio, with James at war, the two women had joined the ‘Phil Ascot Four’. The researcher has discovered that their act in the programme for that Christmas describes how the ‘Phil Ascot Four’ performed ‘The English pony trot’ a new novelty dance of the jazz age. It was one of a number of animal dances in this period that also included dances such as the Grizzly Bear, the Bunny Hug and the Turkey Trot. These dances were considered risqué in the period, and the Turkey Trot was even condemned by the Pope. Sharon is astonished to hear that her grandmother had been so up-to-date with what was fashionable at the time “really they were probably way ahead of their time.”

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

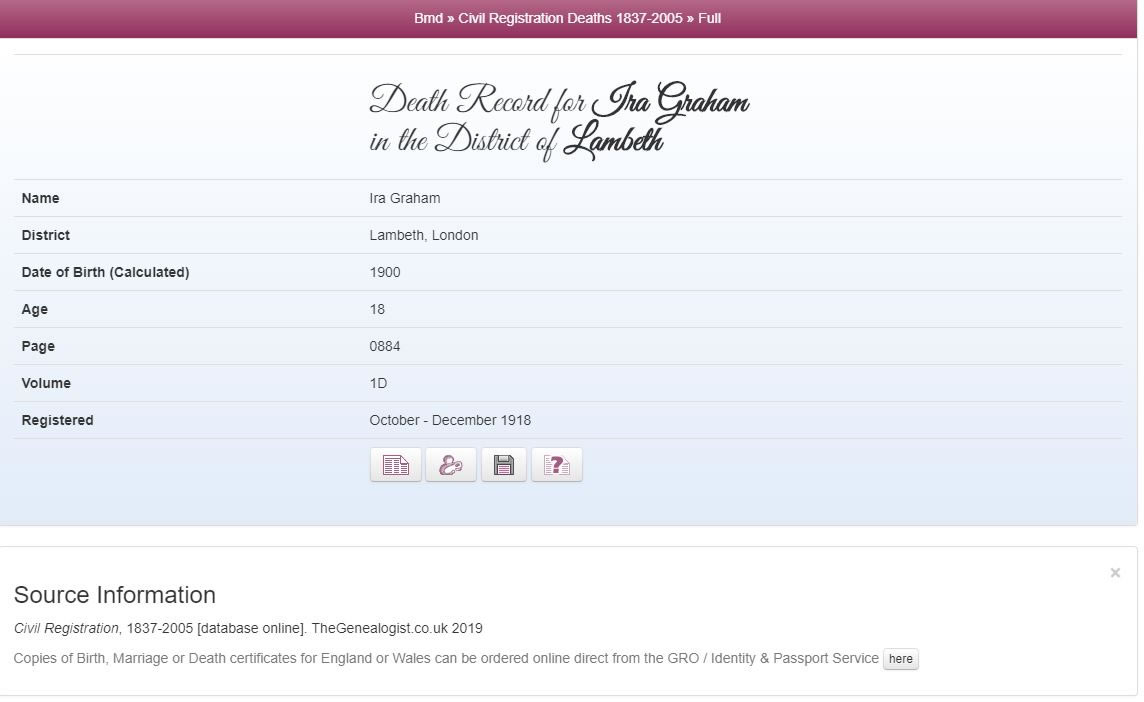

As the war wound on the two sisters, Dolly and Ira, carried on treading the boards. All this time Dolly would also be caring for baby Hope as well. The sisters lived together and travelled together until 1918. A death certificate reveals that in this year, at the age of just 18, Ira died of tuberculosis. She had been suffering from the disease for two years, according to the certificate, and yet she had been performing throughout the course of her illness. Her death, tragically, was just three years before a vaccine began being given to children. Theatres were well known as places where infections could be easily spread and at the time, TB was one of the deadliest diseases in the world, affecting most families in Britain. From the death record it appears that Ira was married to a Sergeant in the army called Archibald Graham, but it was Sharon’s grandmother Dolly who was “present at the death” which occurred at Dolly’s home at 29 Acre Lane, Brixton. Sharon now realises that she has a great deal of respect for her grandmother.

This woman was a hard worker, a very, very strong woman….My impressions of her from a child to now were totally wrong.

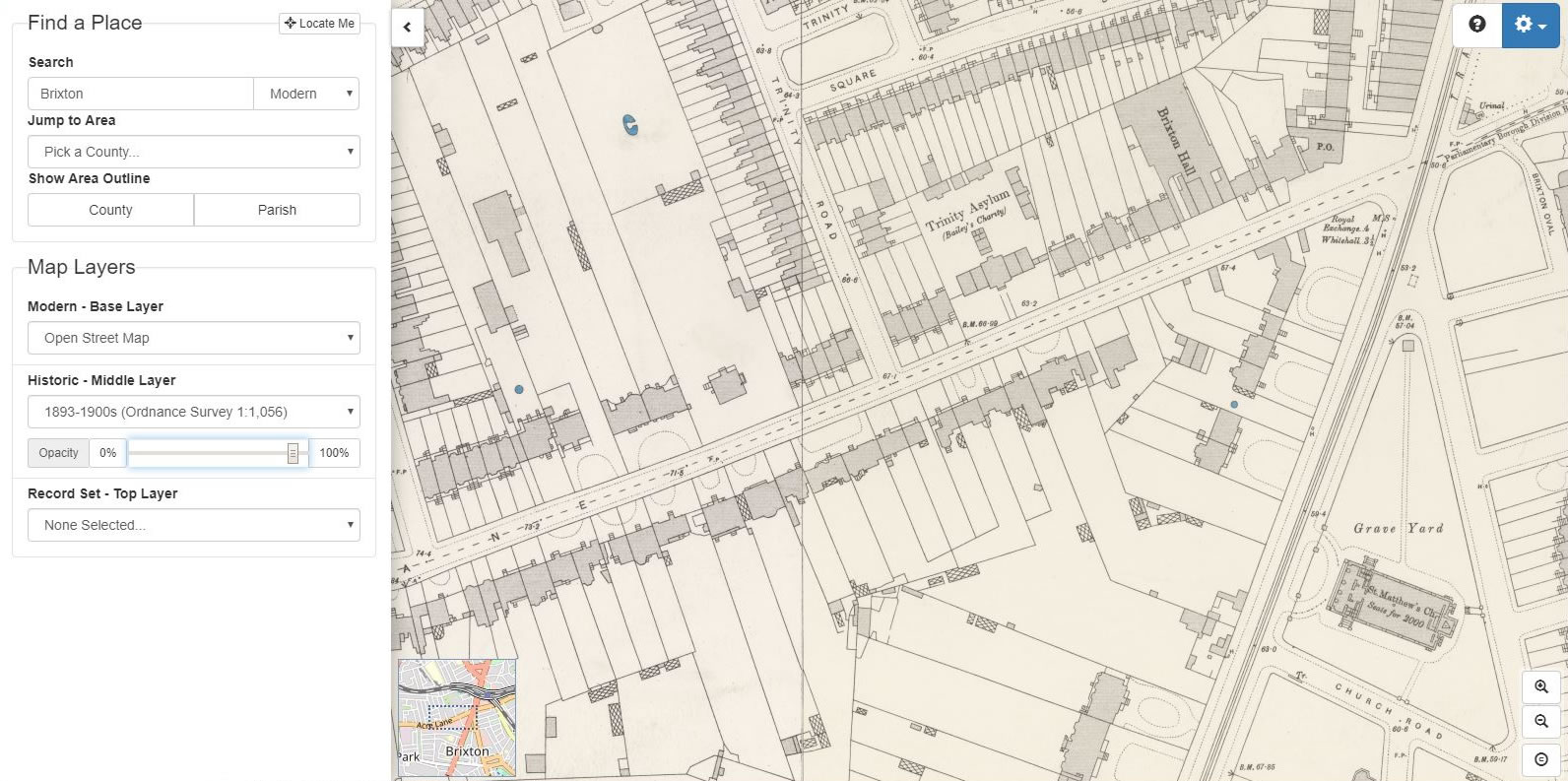

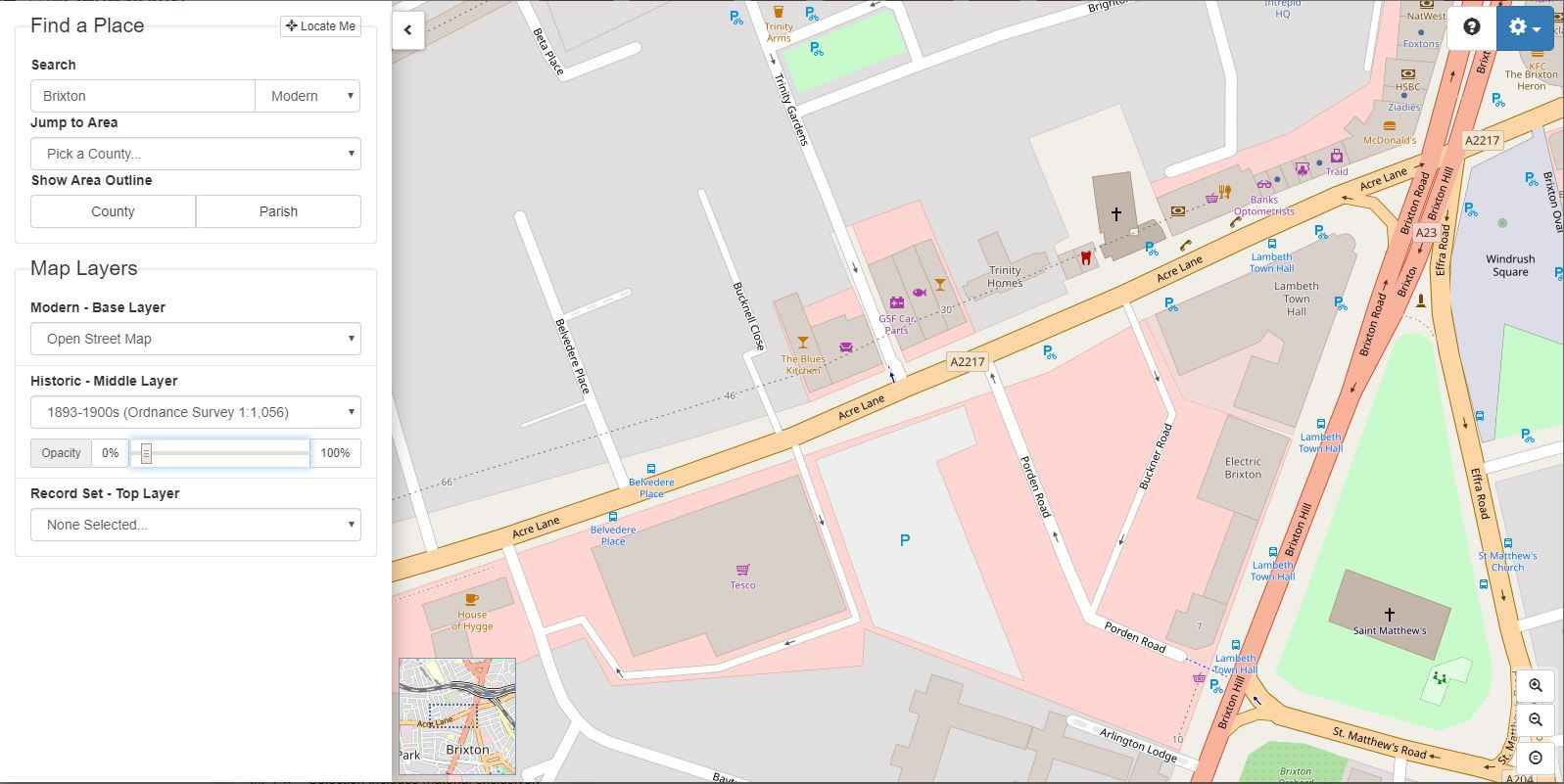

At the end of the First World War, James returned home to his wife and young daughter at 29 Acre Lane in Brixton, South London and in 1920 a second child, a boy, was born. Sharon takes a walk down the road in Brixton where she remembers seeing her grandmother’s house from the window of the bus that she used to travel on with her mother as a child. As we can see, by using the Map Explorer on TheGenealogist, Sharon was going to be disappointed. The house at 29 Acre Lane, and its neighbours, has been replaced by a large branch of Tesco.

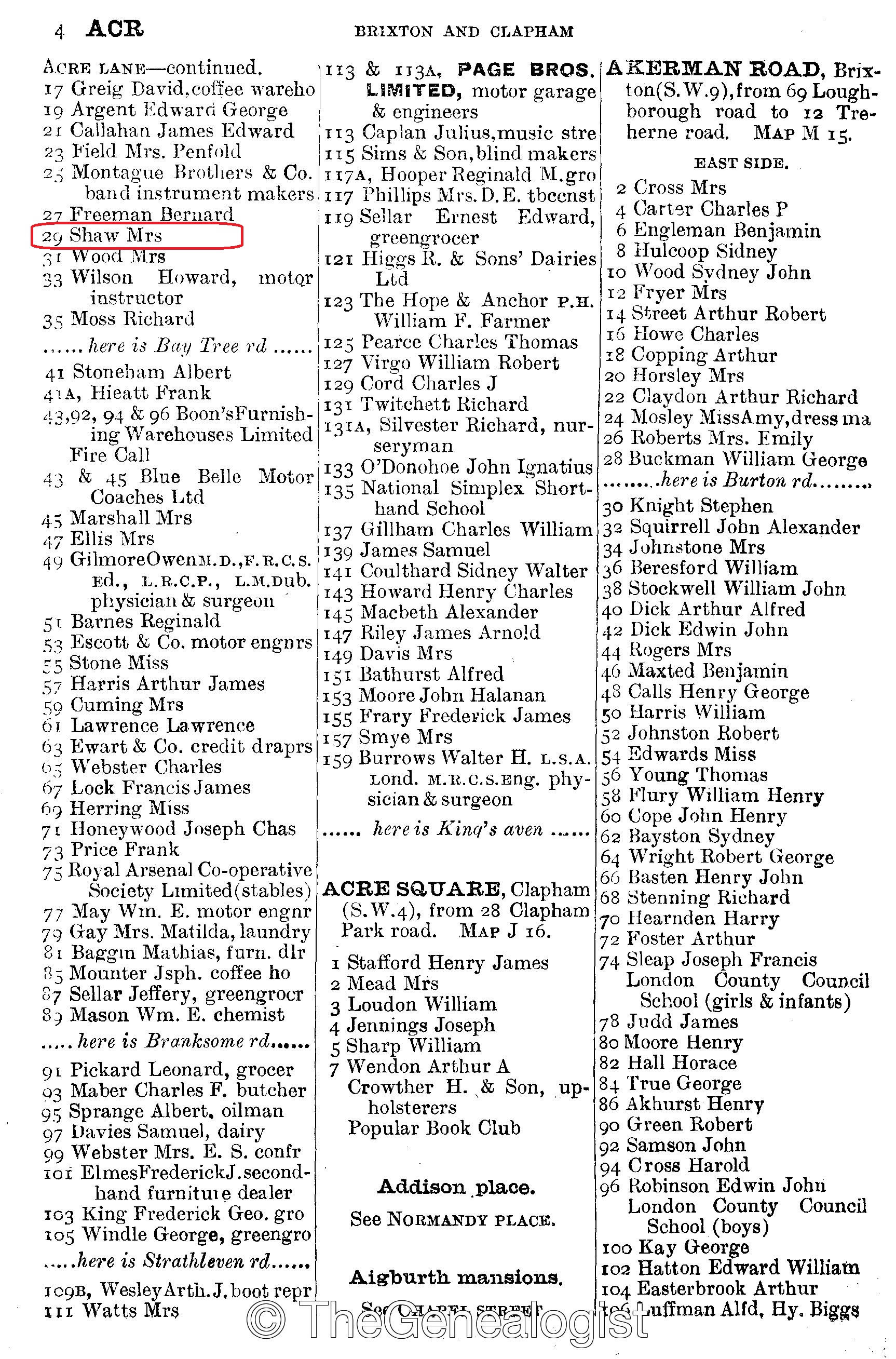

On the screen we see Sharon becoming downhearted to find that the site of the house has been redeveloped into the giant retail store with all traces of the house gone. If we use the Trade, Residential & Telephone Directories on TheGenealogist we are able to find that in 1922 the house at 29 Acre Lane, SW2 is listed in her name only, Mrs Shaw, which may suggest that her husband is no longer living there.

Sharon is able to meet a social historian in a nearby pub to see what she can find out about the Shaw family’s life in Brixton. She starts by looking at a photograph of her grandmother Dolly with her young children; Sharon’s mother Hope is holding onto Dolly. “My mum looks very sweet there.” The historian then shows Sharon a newspaper extract from 1929, its headline comes as a shock; ‘“A Brixton Incident. Mother and daughter charged. Child takes the blame’“.

The article is confusing as Dolly has adopted the name ‘Mabel’ and yet her daughter is still listed as Hope. Sharon’s mother, aged twelve, and her grandmother, thirty-five, were charged with stealing two pairs of stockings and ‘other articles’ to which they pleaded guilty. On being arrested Hope was said to have “exclaimed ‘I will take all the blame if you will let Mummy go”‘. The article tells Sharon that by this time Dolly was indeed now separated from her husband and that she had been out of work, on and off, for around 6 months.

[I] feel a pain in my heart looking at my Mum’s little face in this photo. She’s just a sweet innocent thing holding onto her mum really tight…..my heart really does break for her and it gives me a sense of why she was the way she was.

With the historian, Sharon goes to visit what had once been the site of Lambeth Police Court, where Dolly and Hope had appeared after their arrest and being charged by the police. The building has now become a Buddhist and meditation centre, though the cells have been preserved. Sitting in one of the cells Sharon is able to envisage what it would have been like for her mother, as a young girl, and grandmother when they were kept here. A document from the time shows that they had been arrested on Saturday 12th December and so it seems likely that they were kept in the cells here until they went before the magistrate on Monday. Sharon wonders if, given the timing in December, whether the two may have been stealing gifts to give at Christmas.

Ten years on and Dolly (who was back to using her real name ‘Doris’ again) was now working as a petrol can filler. The date was 1939 and the Second World War had begun. Dolly’s work was classified as heavy, manual work and so that would have allowed her to claim extra food rations. Dolly now listed herself as a widow but whether this was because James had died or just because they were separated, is open to conjecture. What is known is that James has now disappeared from the records and can’t be found.

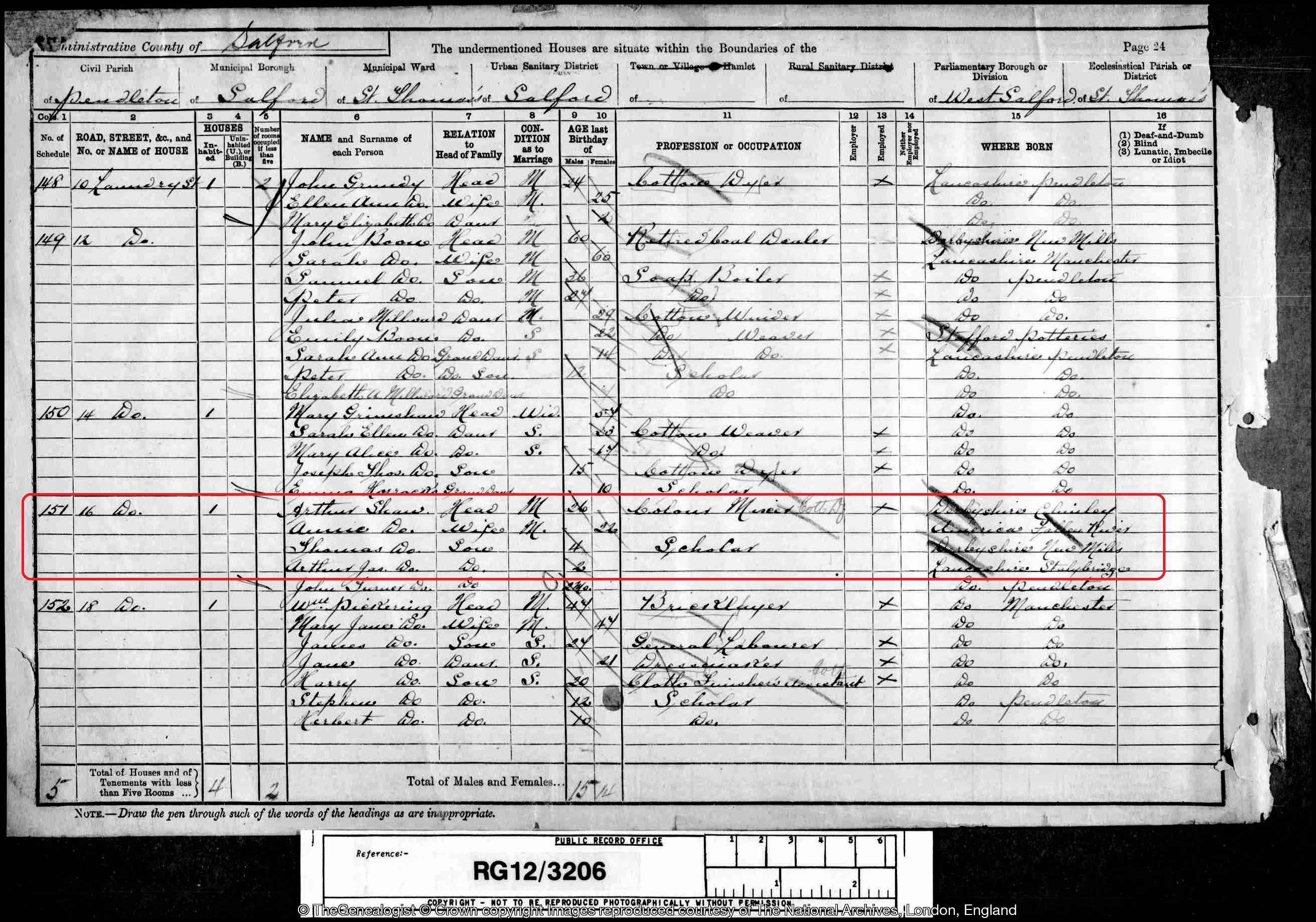

Not having known anything about him, when she set out on this journey into her family tree, Sharon is eager to learn what she can about her grandfather James’s background. The 1891 Salford census shows that he was one of three sons of Arthur Shaw, from Lancashire…and that the children’s mother Annie was from America. Sharon is amazed to discover that she had an American great-grandmother and naturally is curious to find out how and why she ended up in England at this time. The census page records that she came from a place called Fallen River.

Sharon’s next port of call is in the US Newport in New England where she has a meeting with a local genealogist who has been researching her great-grandmother Annie. The American genealogist explains that the place Annie was from was not called Fallen River but is in fact Fall River, in Massachusetts. While she was known as Annie it turns out that she was born Hannah O’Donnell in 1868 to Thomas O’Donnell, an Irishman, and Catherine Dowd, who was English. Annie’s parents were just two of many who had migrated from Europe to the US in the mid-19th Century at a time of famine. Sharon is shown a contemporary travel pamphlet that paints a less than truthful picture of the town and so may have been the reason why they chose to come to Fall River. Sharon reads the glowing description:

Access Over a Billion Records

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

“Its streets are handsomely adorned with shade trees adding much to the comfort and beauty of the place.’ It says that Fall River contains “many elegant residences…And the sunset views from here are said to rival those in Italy.’ If I read this, I would come!

The guide also mentions that Fall River was an important manufacturing centre. As it turns out the city, at this time, was second only to Manchester in England for cotton textile manufacturing. At its peak, 2,000 miles of cotton cloth were made each day in Fall River, Massachusetts. The 1860s saw the United States’ industrial revolution catch up with that in Britain, and transformed the economy from agricultural to manufacturing.

Sharon’s great-great grandparents Thomas and Catherine, according to their marriage certificate, were married in the Catholic Cathedral in St. Mary’s parish in Fall River, so the programme assumes that they met in America. Sharon heads to the Cathedral from Newport and on the twenty mile journey from the more prosperous Newport she sees that Fall River’s industrial past is easy to see in the city’s many old mill buildings. At St. Mary’s, Sharon is thrilled to be able to walk in her ancestors’ footsteps down the aisle of the large church. She humorously has her eyes on the sacramental candles next to the altar: “I’d love some of those candles… with the crosses on. Ozzy would love them. Fabulous.”

In the cathedral Sharon is privileged to sit down and look at the church’s baptismal register, and then the easier to read stack of corresponding birth certificates. She sees the record for Thomas and Catherine’s first child her great-grandmother Annie/Hannah, born on the 17th August, 1868. Then, on 19th April, 1870, Annie’s little sister Margaret was born. Sharon goes through a stack of birth certificates for the O’Donnell children: there’s Annie August 1868; next is Margaret April 1870; then Mary April 1871; followed by John October 1872; then Elizabeth April 1874; and finally Thomas April 1875. Six of them altogether.

They must have been in and out of this church baptising the kids every year. Another one…and another one!

To see what else she can find out about her ancestors’ lives in America, Sharon meets a historian at the Fall River Historical Society, in a former mill owner’s mansion. One of the documents that they had assembled is a contemporary map illustrating images of mills and coal chimney stacks scattered all throughout the town pumping smoke into the sky. The conclusion that they reach is that it would likely have been difficult to see the pretty sunsets that the brochure had promised.

That pamphlet was just a terrible enticement to get these people here. With all of this industry going on, there must have been a constant cloud over here. Must have been a terrible place to live.

Sharon’s great-great grandparents Thomas and Catherine were recorded as employed at Troy Mill. The pay was low Fall River being notorious for this. Catherine, the researcher has found, worked in the carding room where raw cotton was combed to prepare it for spinning and was one of the worst jobs in the mill. Workers were inclined to inhale the cotton fibres that filled the air and so resulting in “brown lung” a disease peculiar to textile mills.

What a terrible place to come to when you’ve got dreams and you leave one country cos it’s so terribly hard there. And you think you’re going to go to a better place and you get here and it’s just so bad.

The enterprises at Fall River used a “family system” of employment. This meant that children as young as six would be employed with their parents in the mills. The situation in America was worse than back in England where child labour laws meant that only children aged nine or older were allowed to work. Sharon asks a question of the expert about what sort of accomodation her ancestors would have lived in. She is told that the company records at Troy Mill show that the workers were required to live in company housing and so owed rent to the company. A family as large as the O’Donnells lived in about 18 square metres with poor sanitation.

Sharon says “I think I’d have taken the next boat back.” But this was not really an option as few would have been able to afford the fare. Sharon finds it “unthinkable”; that her family had been enticed here in search of a better life and then found the reality was that it was a “hell hole.”

As she has seen in the 1891 census of Salford, Lancashire, Sharon knows that her great-grandmother Annie must have left America and come to England. But she is curious to know what had happened to Annie’s younger siblings, Margaret, Mary, Elizabeth, Thomas and John? The sad facts are revealed when she is presented with another stack of certificates. They are all death certificates: Margaret born April 1870, died at 2 months from “convulsions”; Mary born April 1871, died at 2 months from cholera; Elizabeth born April 1874, died at 6 days from “weakness”; Thomas born April 1875, died after 3 months and 29 days on July 6th 1875 from “weakness”; John born October 1872, died in the same month as his little brother, on July 26th 1875, aged 2 years, of consumption.

So all the children but Annie had succumbed to the unhealthy environment. The tragedy continues when, at the age of 35 in 1880, Sharon’s great-great-grandmother Catherine also died of consumption in Fall River. The 19th-century term for tuberculosis, consumption was the leading cause of death in the US. It is at this stage that somehow Sharon’s great-great-grandfather Thomas and his eldest and only surviving daughter Annie left Fall River and moved back across the Atlantic to England. “They were just people…wanting a better way of life, that’s all. They were like pioneers, you know, going off to a new world. And then they come here and it’s worse than what they left. Terrible.”

All these women in the family suffered, all of them – my great-grandmother, my grandmother, my great-great-grandmother – suffered terribly. But they didn’t give up. And I don’t, really. I must have inherited that from Annie.

Sources:

Press Information from IJPR on behalf of the programme makers Wall to Wall Media Ltd

Extra research and record images from TheGenealogist.co.uk

BBC/Wall to Wall Ltd Images

Wikipedia Commons