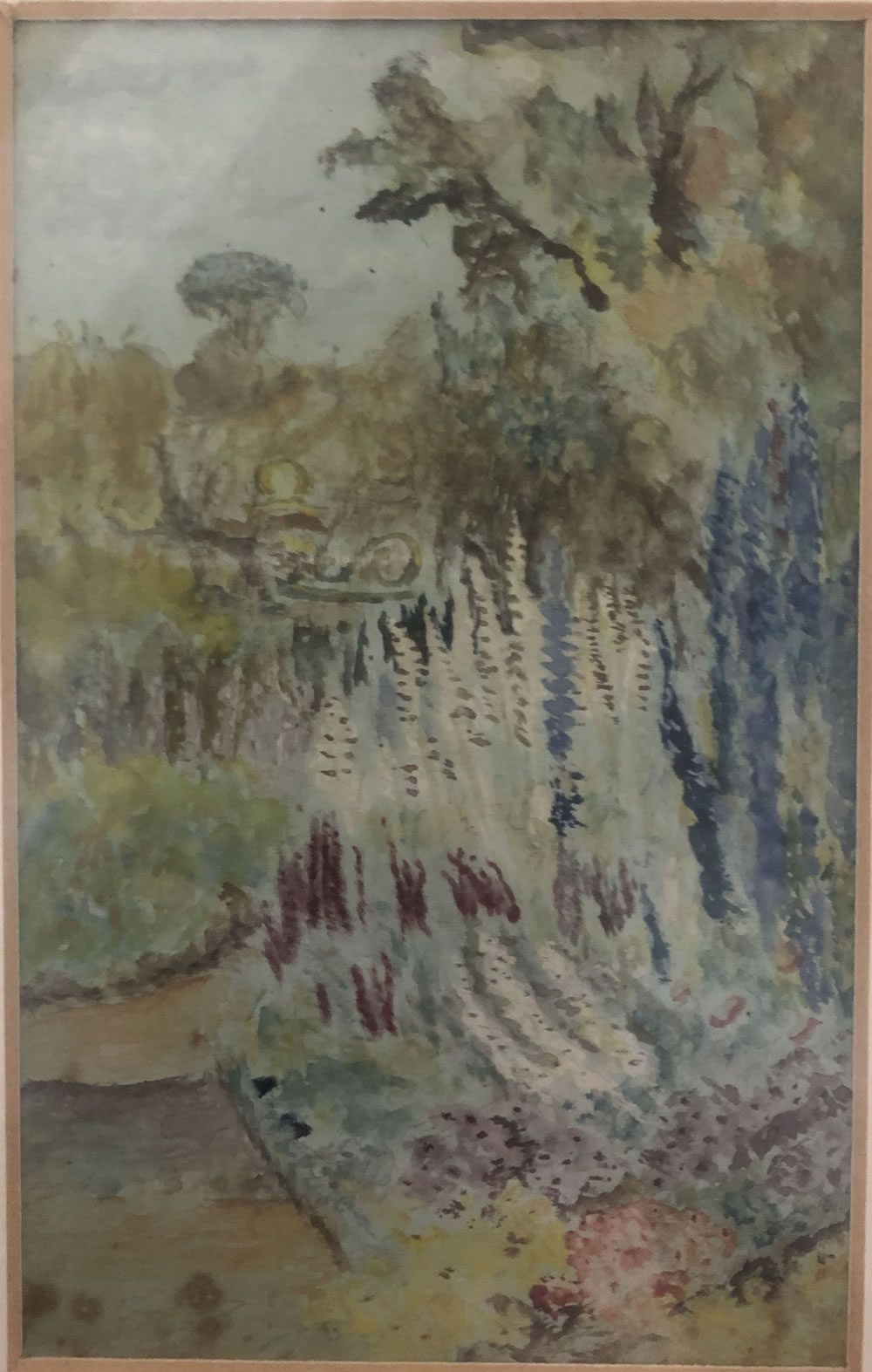

David Edward Williams OBE, known as David Walliams, is an actor, comedian, talent-show judge and best-selling children’s author. Many of David’s children’s books have family relationships as a theme, but David feels he knows very little about his own family history and so he relishes the chance to find out more with the help of the Who Do You Think You Are? programme on BBC television. David has some watercolours at home that he knows were painted by a shell shocked relative of his paternal granny. David likes them because he sees something beautiful and fragile about them. He doesn’t know very much about his mother’s side of the family and so to start the journey he heads to his childhood home in Banstead, Surrey, to talk with his mum, Kathleen.

I now have a family that’s my own family. It’s me, my son and my dogs. And I love being in that family…but it makes you think often about the family you came from as well. And you think well, actually, I would like to know my place in this story.

David and his mother look at a photograph of David’s maternal great grandfather, Alfred Walter Haines. Kathleen explains that Alfred had once run a fairground in Battersea and he and his family lived in wagons on the site. Kathleen explains that her own mother, Violet, seemed to have been uncomfortable with these origins in the travelling fairground community David wonders if perhaps his grandmother thought their family were “a bit lowly.”

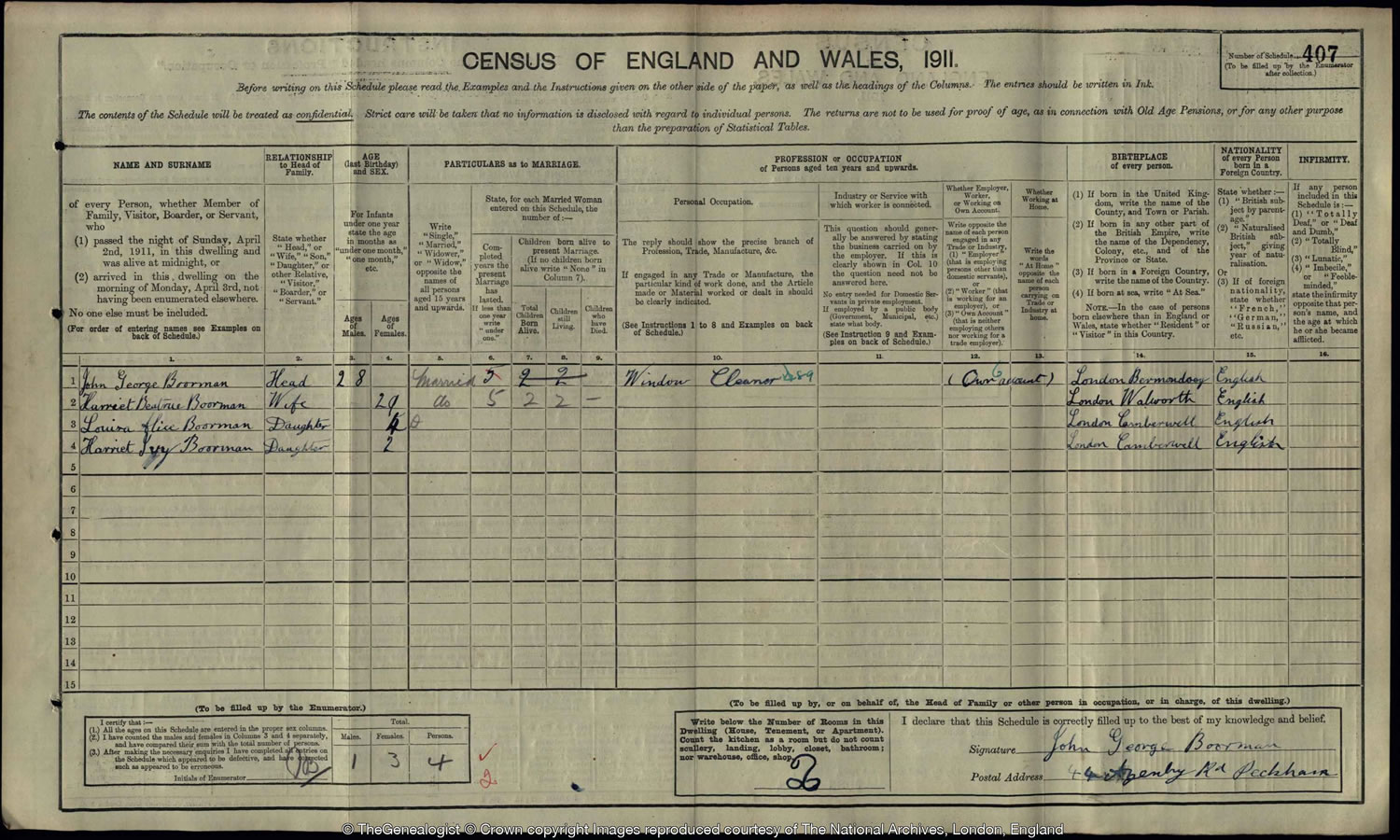

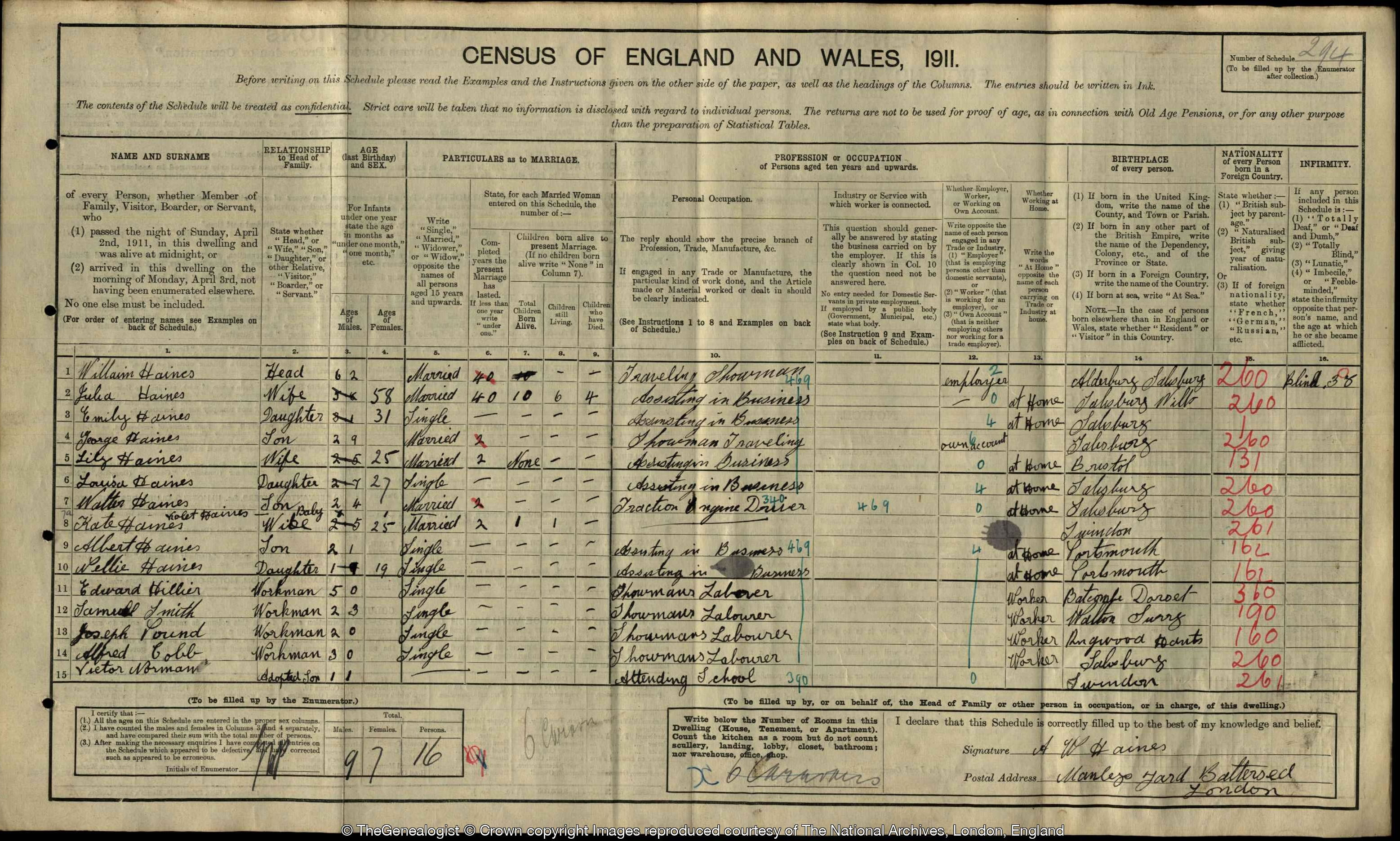

David lost his father, Peter, 13 years ago so he can’t talk to him about his paternal line. On that side of his family, David had been very close to his grandmother Ivy. He can remember that Ivy would tell him a story about a relative who had suffered shellshock after serving in the First World War but David cannot remember who she had been referring to. Kathleen is able to reveal to David that this person was Ivy’s father, John George Boorman and so David’s paternal great grandfather. We can find him in the 1911 census on TheGenealogist where he was listed, at the time, as a window cleaner living in Peckham with his wife and two daughters.

When war broke out in 1914, John’s wife Harriet was pregnant with their third child, a boy. John answered the call of his country and joined the prestigious Grenadier Guards regiment. A poignant postcard, that is shown to David in the television programme, suggests that John was away serving in France at the time of his son’s birth.

I don’t like to be apart from my son for any amount of time whatsoever. So maybe not even to have met your child, while you’re fighting abroad…it’s unthinkable

David travels to central London where he goes to the Wellington Barracks, the home of the Grenadier Guards and is able to meet military historian Jeremy Banning to understand more about his great grandfather’s experiences during the First World War. David finds it interesting that his great grandfather, who was recorded as a labourer when he joined up, had gone into one of the guards regiments with their prestigious standing in the army. Jeremy draws David’s attention to the height of his great grandfather at 5 feet and 9 inches John would have been a tall man for the time. It is entirely feasible that his stature may explain why he was selected for the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards.

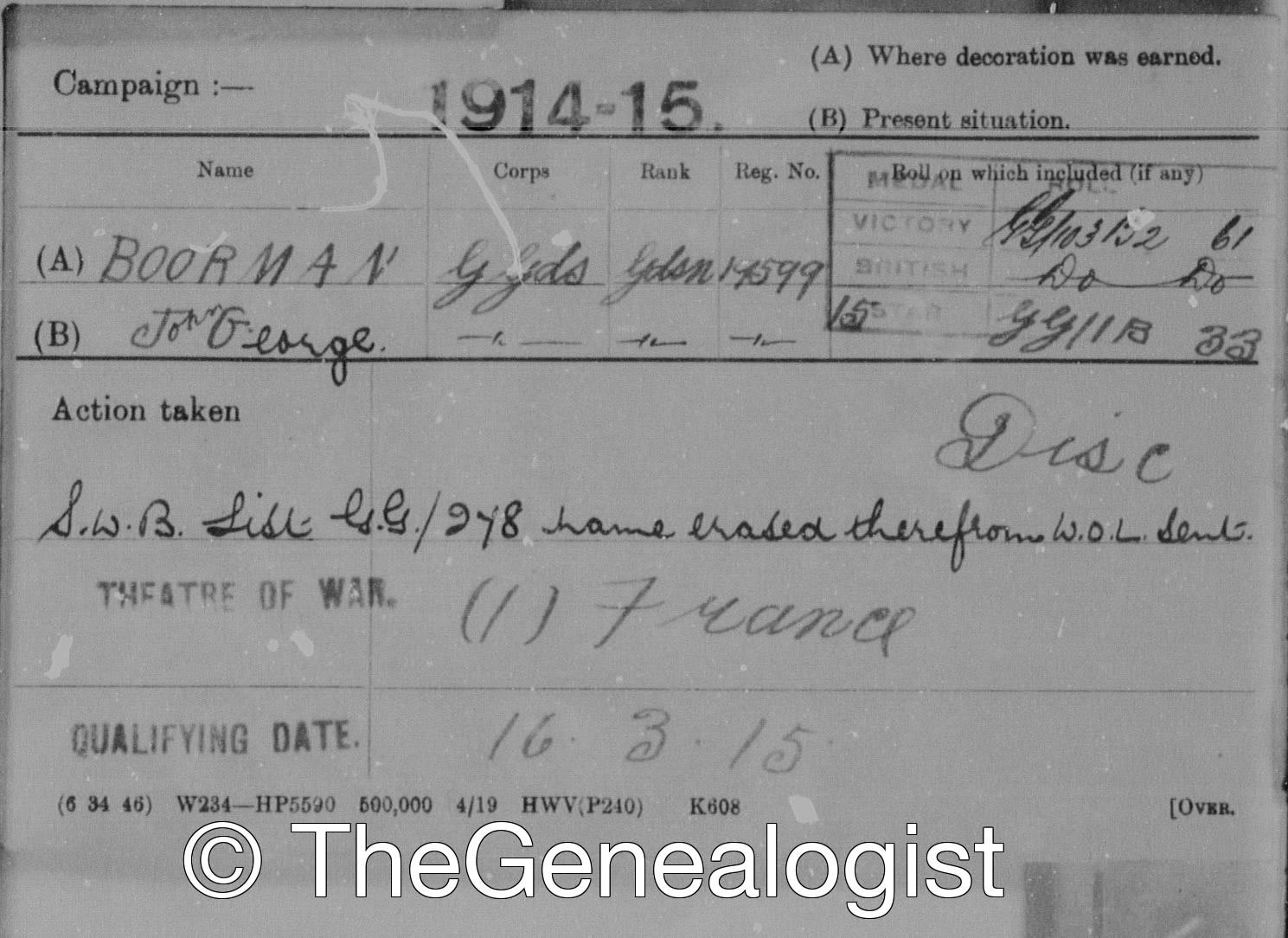

John’s service record shows that he had enlisted quite early in the war in September 1914 and was sent initially to serve in France for a period of 85 days. It was in this period that the Battle of Festubert took place and John would have been involved in the fighting. Who Do You Think You Are? provides David with an account written by a fellow soldier of the engagement. This reveals that both sides inflicted heavy casualties on each other and so this would have been a real baptism of fire for David’s great grandfather, John.

So you’re a labourer one day and then six months later you’re trying to kill someone in a muddy hole perhaps, with your bayonet, with your fist, strangling them, whatever. I mean it’s just terrifying

The records show that John returned to England in June 1915, and remained in the country for an entire year. There is nothing in the documents that explains why, but David recalls a postcard that he had seen earlier at his mum’s house and which may give a clue.

We have a postcard, which is from his family saying ‘Daddy, I hope you get better’. Which makes me think in that time perhaps he was injured

From the army records Jeremy is able to point out that John then returned to France in August 1916. This would have been just in time to be thrown into the Battle of the Somme and to endure the horrors of the Battle of the Somme. John and his comrades then travelled up to Ypres, in Belgium, which had already become infamous by then. He would have been aware that ahead of him was potentially yet another hellish encounter to endure.

I’ve read about the First World War, I studied it at school, I’ve seen movies – but when it becomes a story about my great grandfather John it becomes a human story. As a labourer he enters the Army and finds himself in some of the bloodiest battles of the last hundred or so years. So it’s extraordinary how a person could adapt to those kinds of circumstances

David goes to Ypres in Belgium, following the trail of his great grandfather, to the First World War battlefields. John had arrived here in the summer of 1917 by which time this area had endured three years of fighting that had seen some 100,000 British deaths and turned the terrain into a ravaged landscape.

At Sanctuary Wood there is a section of preserved British trenches, and it is here that David meets battlefield historian Lucy Betteridge-Dyson. John, it turns out, had been stationed in a similar trench just to the north of where they were. The guardsman would have waited, with the other men of his regiment, for the order to be issued to go over the top. This was one of the most notorious offensives of the war, the Third Battle of Ypres or, as it is often known, the Battle of Passchendaele.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

Lucy explains what horrors would have confronted David’s great grandfather on the battlefield. There would have been a shell-scarred landscape before him that was littered with the corpses of fallen soldiers. Attempts were made to bury the dead in the muddy, churned-up ground. The troops, including David’s great grandfather, would have the sobering realisation that this could be where their luck would run out and that this was where they would die.

On 31st July at half past four in the morning the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards, including John Boorman went over the top and advanced towards the German lines. David comments:

It’s very hard to understand how surreal it must have been in a way. With these shells going off all around you, machine gun fire. People dropping dead to your left and right, and you’re just trying to push forward, towards danger the whole time

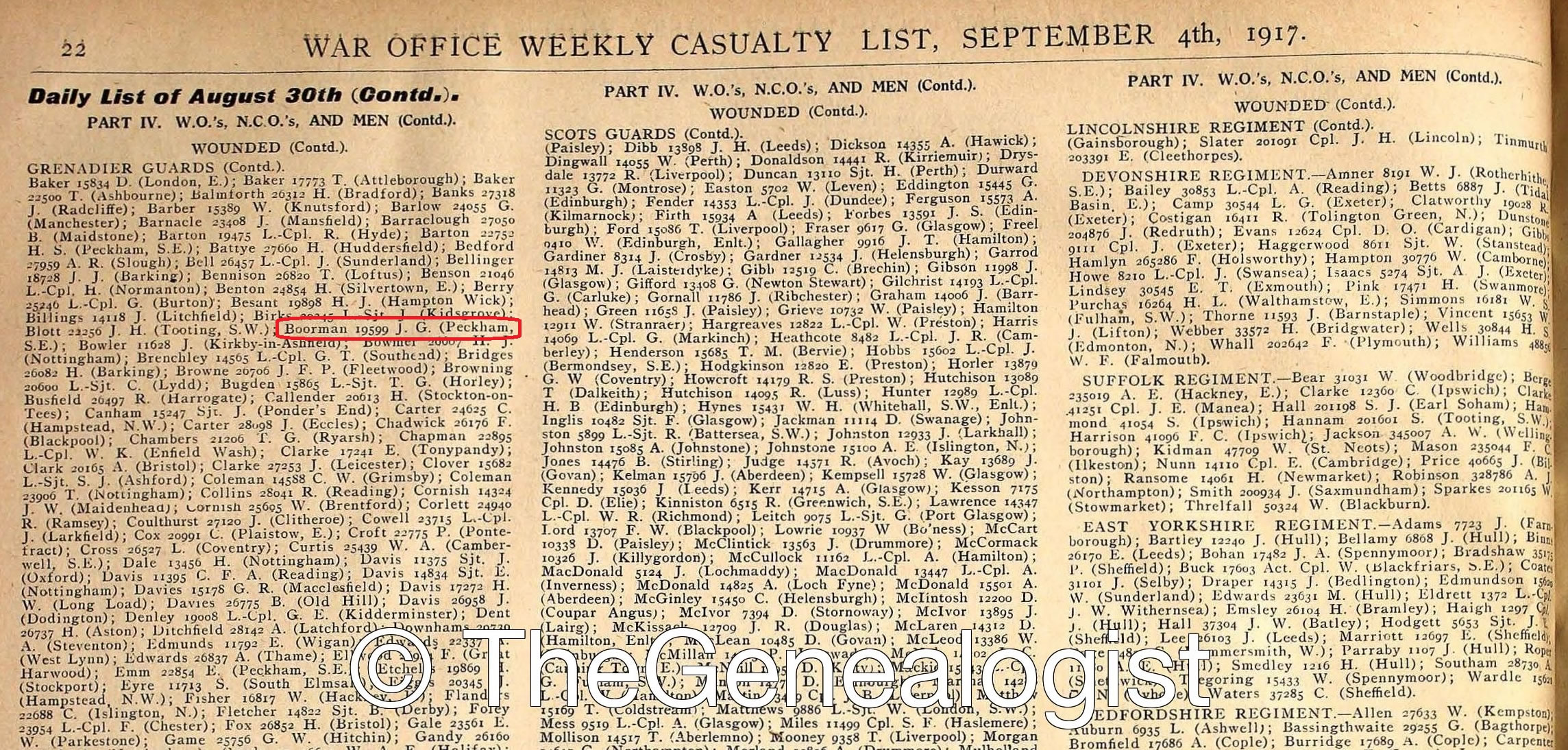

David is shown the War Office Weekly Casualty List dated 4th September 1917 and discovers that John was wounded in battle. The records, which were usually published some time after the event, do not reveal the type of injury that John suffered, but Lucy explains that he was sent home to England. This was the end of David’s great grandfather’s war service as John appears one year later in the records of Napsbury Military Hospital for August 1918.

I can’t help thinking that John was lucky in a way; not lucky to be wounded, but lucky to be out of the war. At the point he was wounded he’d been away fighting abroad for a whole year, which must have taken its toll on him

To see if he could discover more about John’s life, after coming back from the war, David travels to the site of Napsbury Military Hospital in Hertfordshire where he meets historian Fiona Reid. They take a look over John’s medical notes and these back up the family story that David had heard from his grandmother Ivy. David’s great grandfather had indeed been treated for “shellshock”, which today we would call post-traumatic stress disorder. It transpires that John had first suffered shellshock after his very first experience of battle, at Festubert. At the time he had been allowed a year to recover in England and then he was sent back to the front in August of 1916 to take part in the Battle of the Somme and then Passchendaele.

WW1 saw more than 80,000 men diagnosed with shellshock but at this time there was limited understanding of mental illness and so these men were often regarded as emotionally weak or cowardly.

John’s medical notes from 1918, compiled following the soldier’s experiences at the Somme and Passchendaele reveal that David’s great grandfather was by now “hearing voices”. The notes detail that John felt persecuted by these voices and could sometimes be found at a park corner, muttering to himself.

It’s not just what we might consider now…being depressed or something; it’s really strong mental illness. And of course, he’s gone through hell in the First World War in these terrible battles, and the things he’s seen he can’t unsee.

Unfortunately, the story of John Boorman does not end in his recovery and return to health. The TV programme reveals that the next record which can be found for John places him at Cane Hill Hospital in 1939, some twenty years after he was discharged from Napsbury. Cane Hill was then known starkly as a “lunatic asylum.” We see David paying a visit to the site of this asylum in Coulsdon, Surrey, to uncover the end of his great grandfather’s story. It is today being redeveloped but the chapel, particularly the inside, is intact.

From the Admission Register at Cane Hill, John arrived at the institution on 21st October 1919. This was just three months after he had left Napsbury and viewing the document David notices that the word “certified” is mentioned. He realises that John must have been certified insane. It is probable that John had briefly returned to his family home and the care of his wife, David’s great grandmother Harriet. It must have become apparent quite quickly that she could not look after him in his state.

What an awful decision to have to make. To have to send the father of your children, your husband, to a ‘lunatic asylum’.

John George Boorman died at Cane Hill on 28th September 1962, which means that he was a resident at the hospital for 43 years in total.

I’m amazed my Granny had such a sunny disposition, because she had to grow up without a father and in adult life her father was in a ‘lunatic asylum’. And that must have been a really difficult thing to live with

David is able to talk to the historian Alice Brumby to find out more about John’s time at Cane Hill. She is able to tell David that his great grandfather’s life would have been quite regimented in the institution, but not necessarily unpleasant and certainly not punitive. David is shown the weekly programme of entertainment at Cane Hill and sees a list of various activities available to residents: “quiz; talk in club room; elocution class; cinema; radio listening; art class”.

Earlier in the programme David had found out that the paintings he had inherited from his grandmother were painted by his great grandfather. It would seem that this was John’s outlet and so David takes comfort in the idea that, with this creative channel, his great grandfather may have finally been able to find some peace during his time at Cane Hill.

It’s such a sad story. I look at this picture of him, the beginning of the First World War and he looks proud, he’s smiling, he has no idea what horror he’s about to face. You know, he was somebody, he was a father, he was a husband, and he becomes lost. He sacrificed his mental health for his country and the reward was spending the rest of his life here.

I’m glad he had the paintings, and I’m glad I’ve got them. I’m glad they’re still in the family and hopefully they’ll stay in the family forever

David’s Maternal Line

In the Who Do You Think You Are? programme David then turns his attention to look at his mum Kathleen’s side of the family. He already knows from his mother that his great grandfather, Alfred Walter Haines, had once run a small fairground in Battersea, London. David is able to see Alfred’s marriage certificate which shows that his great grandad married David’s great grandmother in 1909 in Salisbury. On the marriage certificate, under the “occupation” heading for Alfred’s father (David’s great-great grandfather), William Haines is described as “blind”.

Access Over a Billion Records

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

The BBC TV show follows David when he travels to Salisbury, the location given on the Haines’s marriage certificate, to speak with historian Julie Anderson. They meet at the General Infirmary in the city and Julie explains that David’s great-great grandfather William had been a patient at the hospital in 1884. He was undergoing posterior cataract surgery to the back of his eye. The operation, however, was unsuccessful and so this is how William ended up blind.

William J. Haines is on the 1891 census and is surprised to see his occupation given as “musician”. The document also reveals that William was now living in Portsmouth and so it is here that David meets historian and showman Tony Lidington at the Historic Dockyard to find out what William played.

Tony reveals that William was actually a street entertainer who played a barrel organ perhaps also with a monkey as part of the act. Tony has brought a barrel organ with him to the docks and demonstrates how a handle is turned to play a pre-set melody whilst the entertainer sings along. He then invites David to try for himself.

I don’t think you’d go very far on Britain’s Got Talent… just doing that

Tony has a copy of an article in the Western Chronicle, dated 27th November 1896, which reports on a charge against William and Julia Haines under the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act for sending their children on the streets to sing and play for the purpose of begging. The children involved were 9-year-old Alfred Walter Haines, David’s great grandfather, and his sister Louisa.

My great-great grandfather and his family seem like they were dirt poor. I mean they, they were travelling around. He was blind. He was begging on the streets, and not just that, the children were involved in the begging too. That’s something my Granny never told me about

David views the 1911 census and finds that by this time William Haines is now listed as a “travelling showman” living at 88 Manley’s Yard, Falcon rd, Battersea, London. Following the trail of the Haines family, David then travels to Battersea in London in order to talk with historian Jodie Matthews. She is able to reveal that, in the early 1900s, the Haineses operated fairground rides including shooting galleries and roundabouts.

Fairs were a hugely popular entertainment of the era as people had more leisure time with the move towards a five day working week, and the introduction of summer holidays. Showmen saw the opportunity and provided amusements for the population, very often employing their whole family to run the rides.

Although many people at this time looked down on itinerant families like the Hainses being suspicious of them, an article from the time suggests that in fact the Haines family’s own lodgings were clean and well looked after. Jodie shows David a photo of a wagon similar to the one the Haines family would have lived in.

I love it. It’s actually really romantic isn’t it? It’s beautiful. What an extraordinary lifestyle

David is able to visit a storage facility for a steam fair in Maidenhead and to meet fairground historian Graham Downie there. David loves the brightly coloured wagons and rides parked up all around him. Graham tells him that Manley’s Yard would have looked very similar.

David wants to know whether his great-great grandparents would have made a good living with their rides. Graham is able to reveal that the Haines purchased a showman’s traction engine for £1400, which equates to around £160,000 today. David is glad to learn the family’s circumstances seem to have improved from their earlier times when they were taken to court for sending their children out to sing on the streets for money. Graham has found a newspaper obituary for William published on 24th November 1913, which reports how he overcame a poor upbringing and the loss of his eyesight to become a successful showman.

When David’s great-great grandmother, Julia, died ten years later her obituary said that she was well-known across London and the southern counties and that her death was mourned by a large circle of friends. The article is accompanied by a picture of Julia, and David observes that she looks rather magnificent.

Another photograph that Graham is able to show to David is of the fair at Falcon Road. David realises that these had to be the dodgems that his mum recalls riding in the 1940s. One more photo of a group of boys is shown to David. These are thought to be David’s great uncles, the brothers of David’s grandmother, Violet. David is struck at how one of the boys look like his uncle.

When David’s great grandfather Alfred died in 1951, he was no longer involved in the fairground business. David laments the loss of the showman tradition in his family but Graham suggests “you’re back in it”. David replies:

Very kind of you to call me a showman. Certainly a show-off!

I love my great-great grandfather’s story. It’s a real story of resilience. To lose your sight…to then be working a barrel organ and go on to be a very celebrated showman…I can’t help but be proud of him

And I couldn’t be prouder of my great grandfather John George Boorman. He fought in the First World War, but sadly he lost his sanity. It’s a really, really sad story but I think they’re both really inspiring people and I’m so glad their stories have been told

Sources:

Press Information from Multitude Media on behalf of the programme makers Wall to Wall Media Ltd

Extra research and record images from TheGenealogist.co.uk

BBC/Wall to Wall Ltd Images

Wikipedia Commons