Image above: Sue Perkins in London, where her immediate ancestors lived. Credit: BBC/Wall To Wall Media Ltd/Stephen Perry

Comedian and TV presenter Sue Perkins describes herself as a very driven person, who feels a historical hand

in the small of my back moving me on

. Her episode kick-starting the new 2022 series of Who Do You Think You

Are? certainly corroborates that. The engine of social history is grafters,

she observes, and I have a

real sense that whatever privilege I have is on the back of people who had nothing and worked for

every scrap.

In this article we’ll use online resources at The Genealogist to look at the context a few of the family members whose lives are explored in the programme without revealing too many spoilers, of course!

Sue Perkins was born in East Dulwich in south London in 1969 and of course is well known for her collaborations with Mel Giedroyc, on stage and on screen, particularly for their stint as presenters of The Great British Bake Off, and Radio Four listeners will also know her as the late Nicholas Parsons’ successor at the helm of Just a Minute.

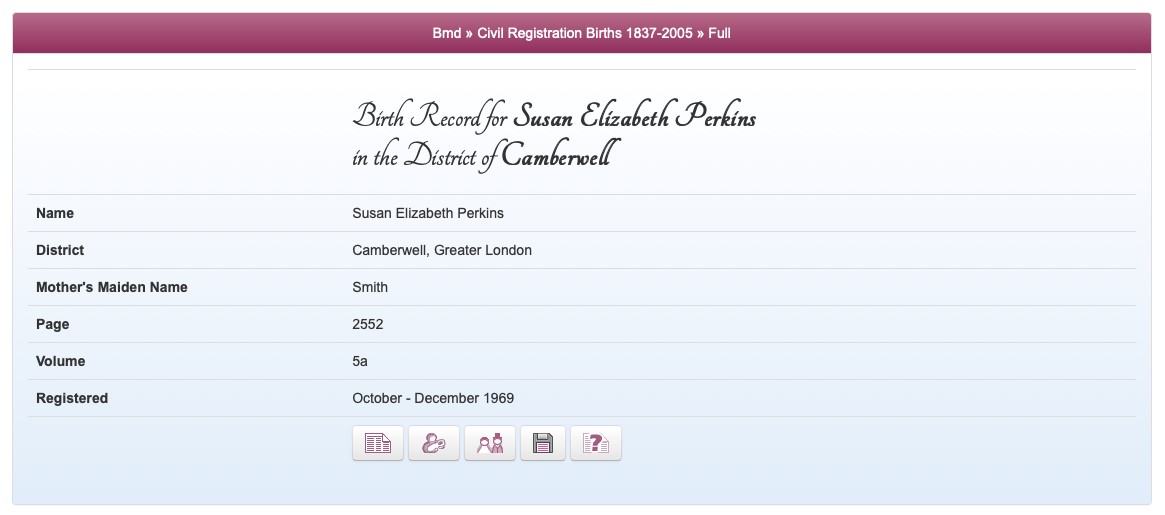

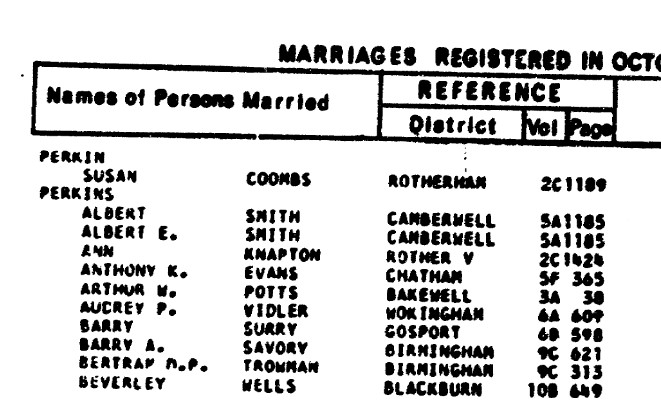

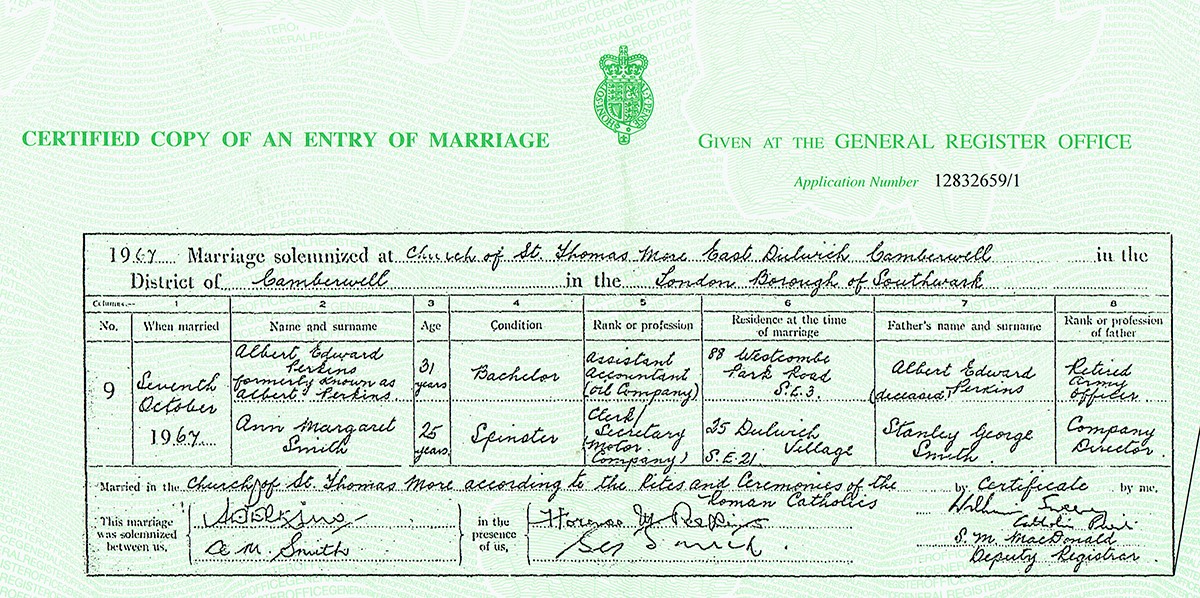

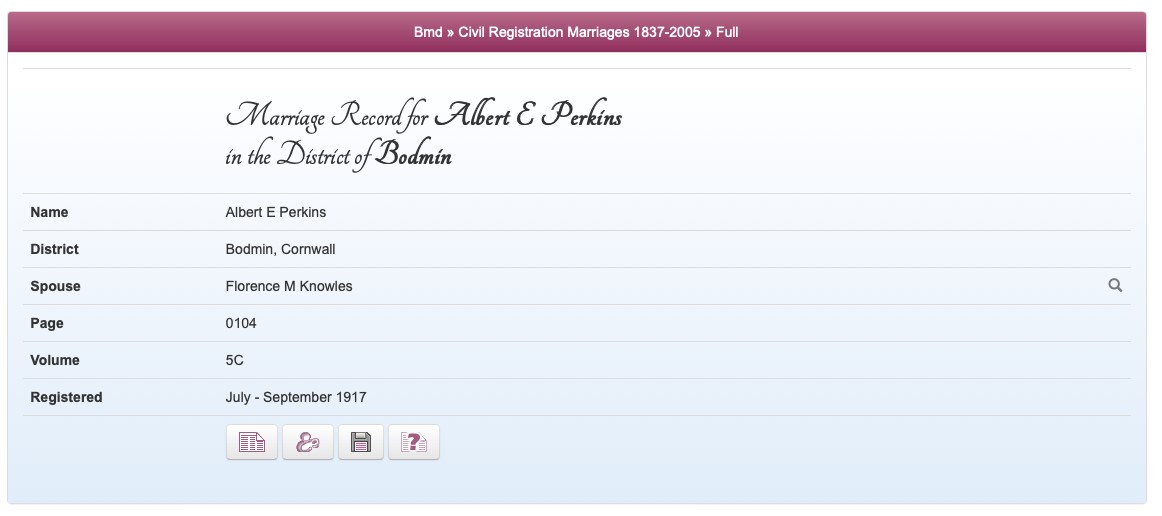

Susan Elizabeth Perkins grew up in Croydon, daughter of Albert ‘Bert’ Perkins and Ann M. Smith. A search of The Genealogist’s birth, marriage and death indexes soon provides references for both her birth registration and, via the site’s SmartSearch feature, her parents’ 1967 marriage, both events being registered in Camberwell District. Interestingly, the index shows her father twice ordering the actual certificate from the General Register Office reveals that her father is given as ‘Albert Edward Perkins, formerly known as Albert Perkins’. His own father, the TV presenter’s grandfather, was also Albert Edward Perkins, so perhaps Bert only restored the middle name after his father’s death, to avoid confusion between them.

The marriage certificate shows Bert who sadly died in 2017 after battles with different cancers was then an assistant accountant for an oil company, although later in life he was known as a much-loved character working as a car dealer in Croydon. Sue’s mother Ann (née Smith), whose life isn’t touched on in the TV show, was herself in the motor trade as a secretary when they got married. The marriage certificate provides details which can help us push back to the previous generations, thanks to details of Sue’s two grandfathers Albert Edward Perkins Sr listed here as a retired army officer, and Stanley George Smith as a company director.

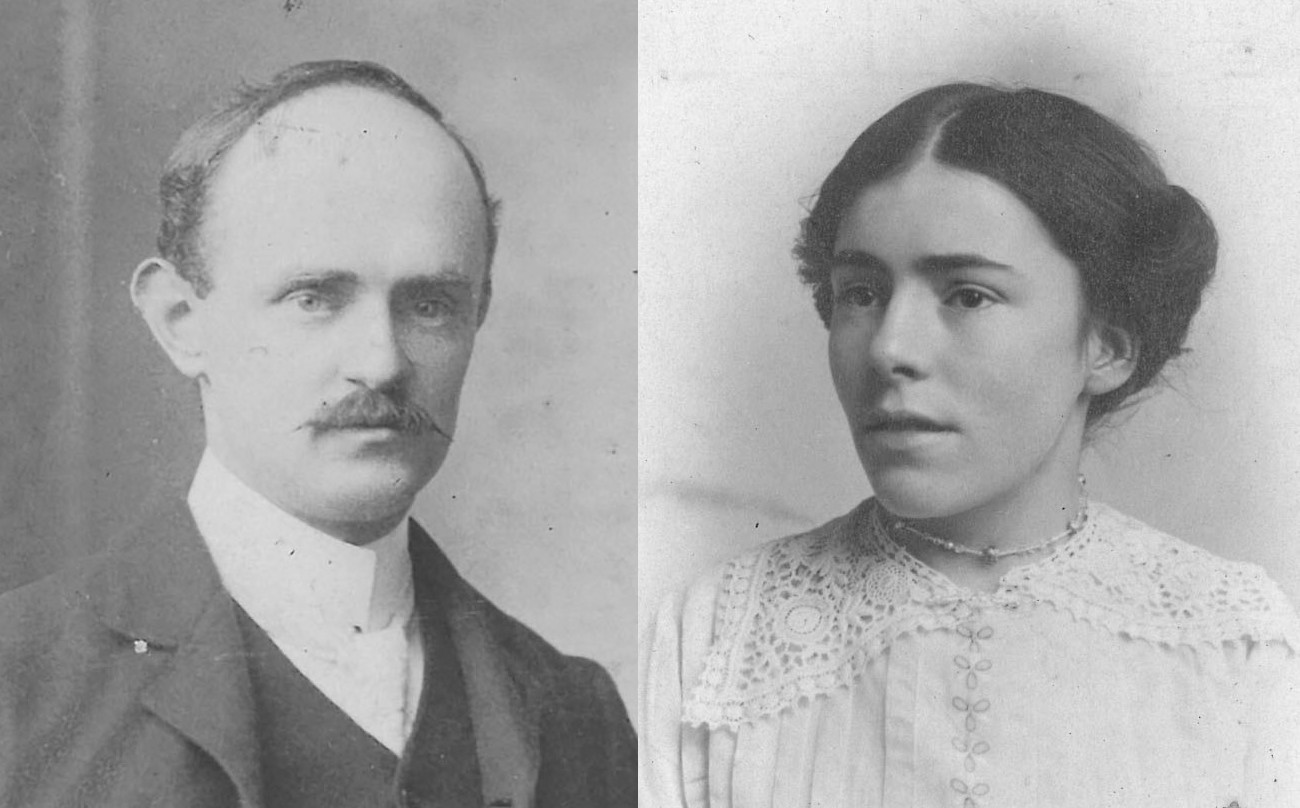

Much of the TV show focuses on the lives of Sue’s grandparents. On the paternal side, a family photo underpins her

mental image of Albert senior as a rather stern and remote figure, although she remembers her grandmother Florence

Mary as the kindest person I’ve ever met

. Some genealogical detective work, though, reveals that one reason why

her grandfather might have seemed rather Victorian is because… well, he was: he was in fact born way back in 1875 in

Axminster, Devon and was into his 60s when Albert junior was born in 1936. Again, indexes for Albert senior’s birth

and his 1917 marriage to Florence May Knowles can be found at The Genealogist. This union took place in Bodmin,

Cornwall (it was at the Roman Catholic church) Sue quips on the show that her grandfather was rather like Bodmin

Moor to her, bleak, remote and utterly knowable

.

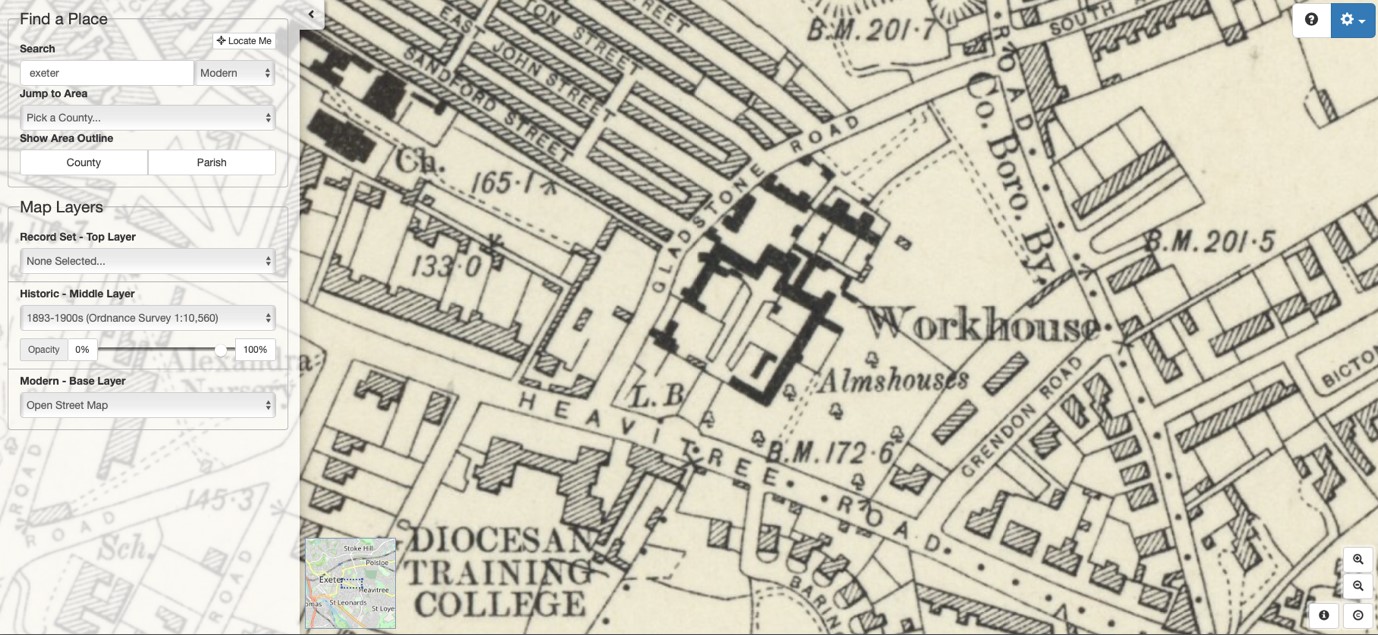

Without giving too much away here, it transpires that Albert senior’s childhood was marred by a series of tragedies which meant great hardship in his early life. His own father, Henry Perkins, sadly died in Exeter Workhouse in 1882, a place which continued to cast a shadow over young Albert’s life. Henry’s cause of death was phthisis, now known as tuberculosis. His death registration index record at The Genealogist reveals that he was born c.1830

By the time of Henry’s death this workhouse had become a Poor Law Union. We can use The Genealogist’s powerful Map Explorer feature to pinpoint this site on an 1890s map, only a decade or so after it played such a central role in the Perkins family history. A report on workhouses by the British Medical Journal in the same decade (available online via www.workhouses.org.uk) reveals that the building could house up to 550 inmates, although half that number lived there at the time, noting the ‘thin and untidy’ bedding and ‘the large number of sick and helpless patients in the infirmary’.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

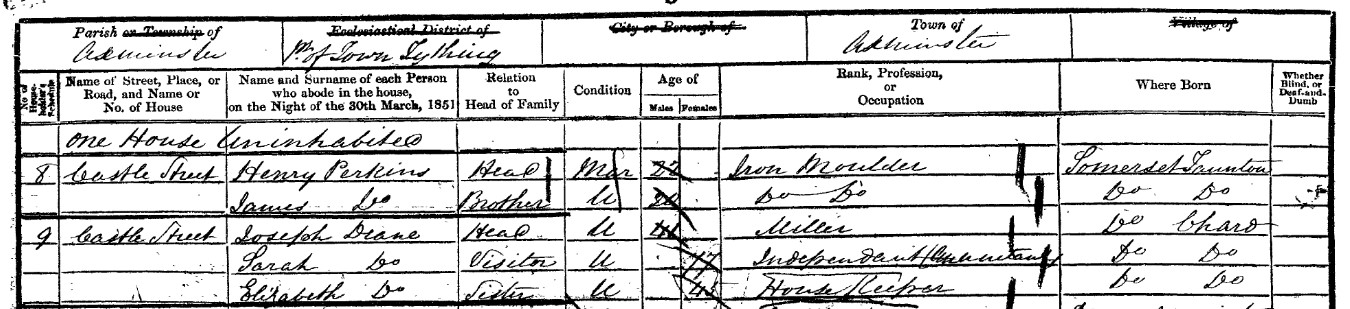

Looking back in time to Albert senior’s parents, whose lives are not explored in the TV show, we can see that although Henry Perkins died in straitened circumstances, at the time of his son’s birth he was still in work, as a railway signal fitter. Looking at the census records on The Genealogist, we can also see Henry Perkins in his 20s back in 1851, living with his brother James in Axminster, with both of them working as iron moulders, and we learn they were born over the border in Taunton, Somerset.

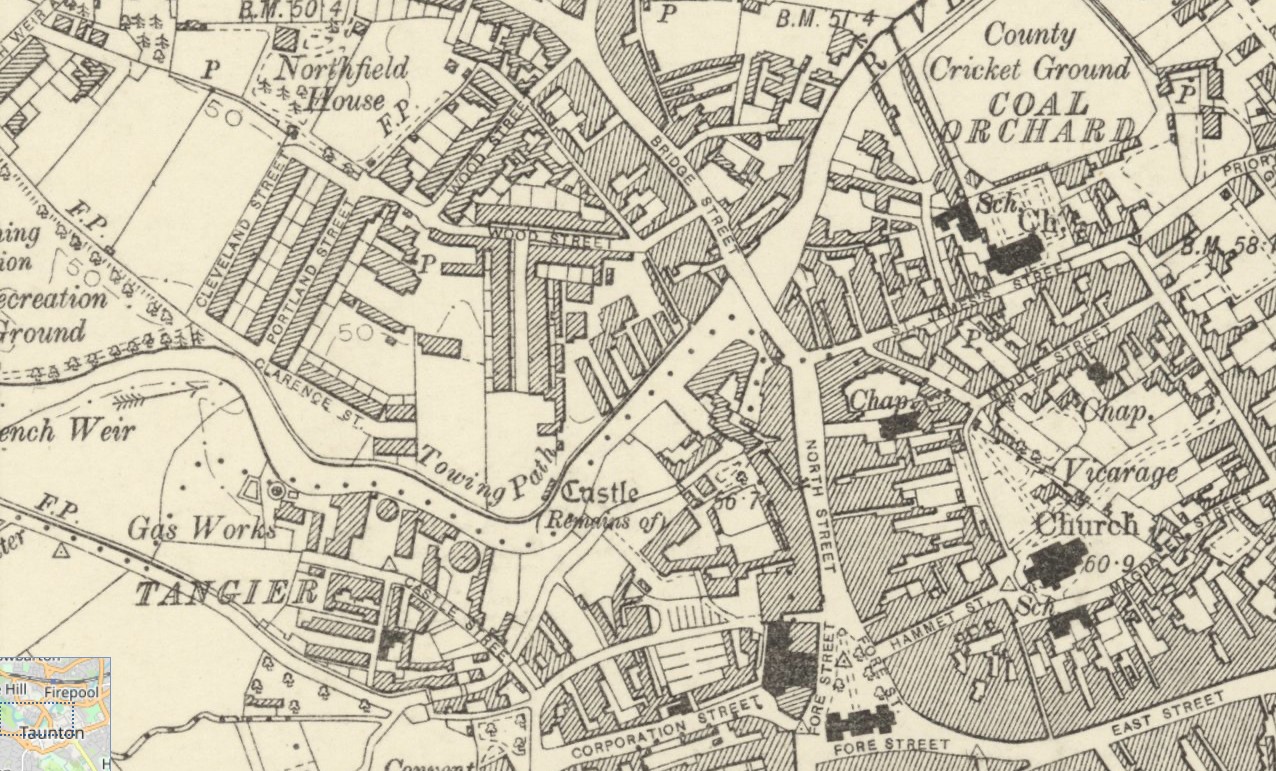

We can push further back, too, using the site’s 1841 census records: Henry and James are both listed back in Taunton, where their father John, in his 50s (bearing in mind that the 1841 census only recorded adults’ ages to the nearest five years), is listed as a ‘moulder journeyman’. As the name suggests, an iron moulder’s job was to make moulds for casting iron this would typically be done in a foundry, but presumably as a journeyman he was more of a freelance, finding work wherever it was available. We know that Taunton had at least two iron foundries in the 19th century the St James’s foundry was in fact in Foundry Road (also called St James’s Street details of the foundry’s history are online at www.somersetheritage.org.uk/record/14501) among other things it made street furniture and gratings; plus Cox’s Foundry (also called the Tangier Works) was on Castle Green, and even produced tokens used as currency when there was a shortage of copper in the early 19th century (see www.gracesguide.co.uk/Cox%27s_Foundry ).

Being an iron moulder would have been hard and dangerous work in sweltering conditions although presumably the advent of the railways at least enabled Henry to escape the confines of the foundry for his new role as a signal fitter. Nevertheless, this could still be a dangerous job mechanical signalling was introduced in the 1830s to replace hand signalling, but the system of ‘block signalling’ (where only one train was allowed in a certain section of track at a time) only came into use in the 1850s and 1860s after many accidents. Working on fitting the signals would certainly still have exposed men to danger from passing trains.

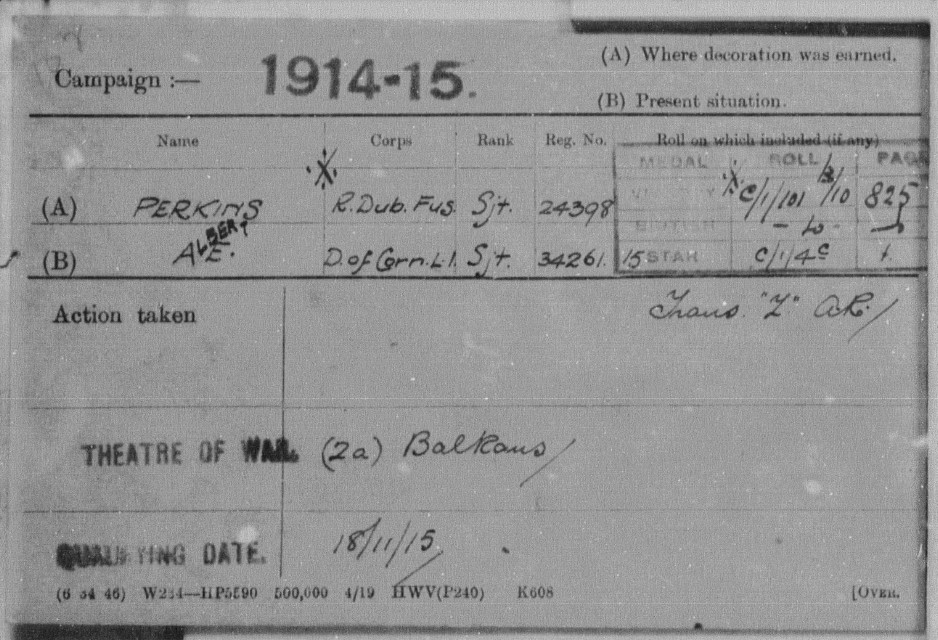

Returning to Albert senior himself, when he married Sue’s grandmother Florence in 1917 smack in the middle of the First World War he was listed as a sergeant, while she was a nurse. Fortuitously, The Genealogist’s extensive Military Records collection enables us to learn more of his military career. The site has his WW1 medal index card, which reveals that he served with both the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry the latter perhaps unsurprising, as they were based in Bodmin. And we also learn from this card that he saw service in the Balkans a part of the world which turns out to have further significance in Sue’s ancestry, but you’ll have to watch the show to find out why!

Here we’ve only looked at one branch of Sue’s family, pushing it back to the early 19th century using online records, but her episode of Who Do You Think You Are? reveals that there were some tough times endured by her ancestors on her mother’s side, too, with a moving story of roots and great challenges in the war-torn Europe of the mid-20th century.

Ultimately on both sides these are stories of what Sue calls extraordinary ordinary people

: They made

extraordinary things happen for themselves. They grafted.