When we set out to look into our family history, sometimes our research may cause a skeleton to fall out of the closet. For some this is exciting, while it can be embarrassing for others. If you are tempted to judge your ancestors, remember that they lived in different times from which we do today. Their reasons for covering up an event may seem completely logical to them, while to modern eyes it seems a bit odd.

One of the “skeletons” that may make an appearance in many families is that of an illegitimate ancestor. Often, without knowing the father’s name, a researcher may wonder how to carry on tracing a family line back any further. Discovering that someone was illegitimate, however, does not always mean that your research has hit a brick wall. Sometimes the clergyman may have made a note in the margin of the parish records that will help you, but that was not the norm.

You may pick up a clue to the putative father’s identity by taking note of the names that the child is given; sometimes the father’s surname would be used as a forename or middle name for the baby. You can also check to see if there was a marriage for the mother shortly after the birth or baptism, as the father may have offered or been persuaded to marry the mother of his child. Using the Parish Records you should search to see if a child was given their mother’s maiden name as their surname at baptism, but then adopted their father’s surname for the rest of their life.

Another set of records that you might use are Bastardy Bonds from the parish records. TheGenealogist has just released, in association with the Norfolk Record Office, these particular records for this county in eastern England.

Bastardy examinations

If you are searching for an ancestor before 1834, it should be remembered that when a father of an illegitimate child was unknown, the parish was responsible for the boy or girl’s maintenance. It was for this reason that the parish officials, known as the overseers of the poor, would be very eager to find out the father’s identity and so shift the burden from the parish funds onto the father. In some cases the mother may have gone voluntarily to the local justice of the peace, or she may have been summoned and required under oath to give them the name of the child’s father. The consequence of non-compliance was facing a spell in jail.

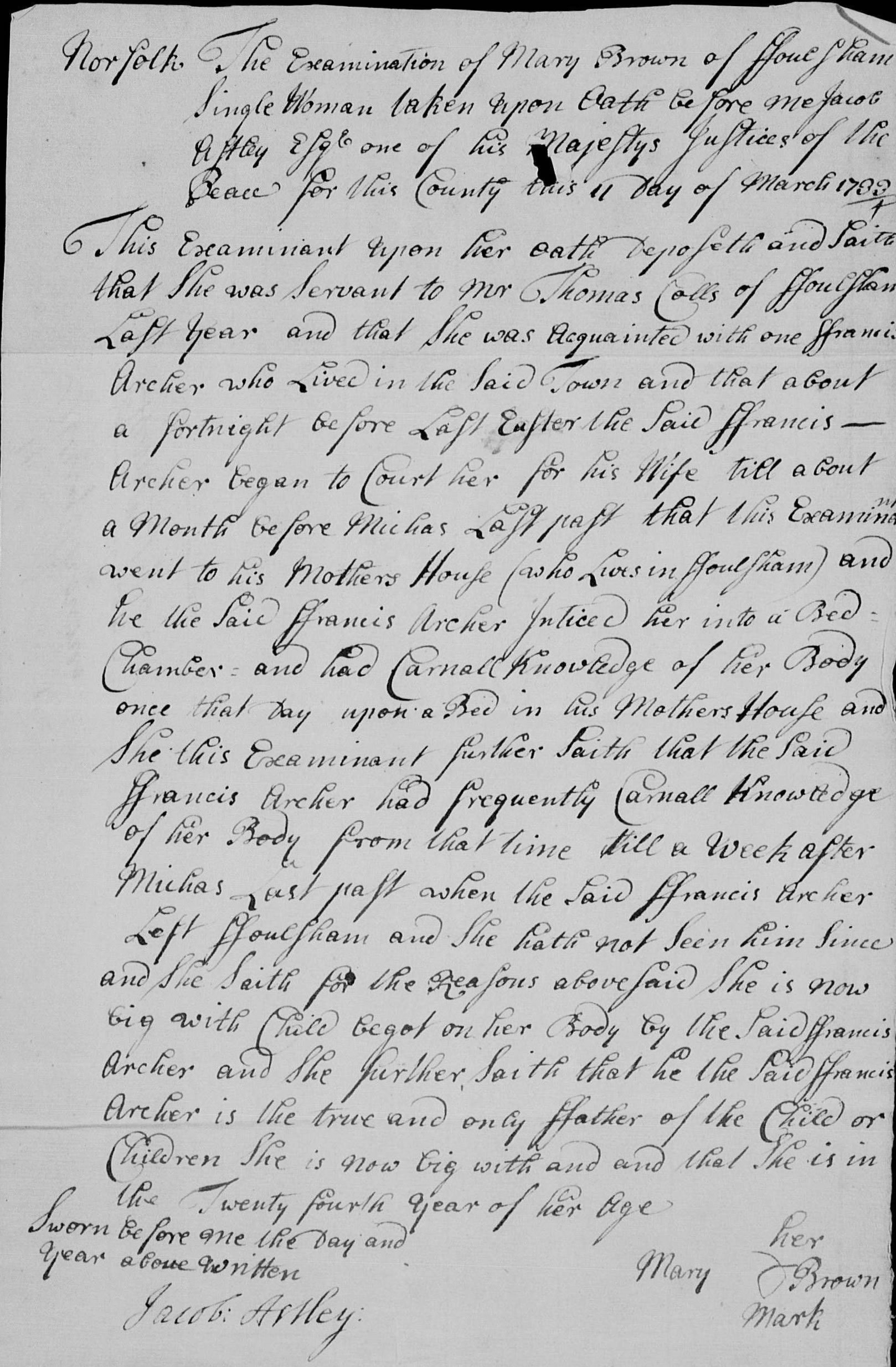

From our records we can look at the examination of one Mary Brown of Foulsham, Norfolk. She was a single woman who appeared before the Justice of the Peace on the 11th March 1733. It was written down in the records that she had been a servant to Mr Thomas Colls. Being acquainted with Francis Archer from the town, she “allowed him to court her for his wife”. Archer enticed her into a bedchamber at his mother’s house and then had “carnal knowledge of her body”. The examination then reveals that Archer went on to do the same frequently… and then he ran away. Twenty-four year old Mary Brown was now big with child and had been compelled to name Francis Archer as the father of her child in a sworn statement before the Justice of the Peace which she signed with her mark. Armed with this information from her Bastardy examination the Churchwardens of her parish could now pursue the father for maintenance.

Bastardy bonds

Once the parish officials had the name of the presumed father then they would pay him a visit and put him under pressure to marry the mother. If he refused to wed, or could not marry the woman, then he could agree to pay a weekly maintenance for his child, or hand over a lump sum having admitted paternity of the boy or girl. The documents generated in these cases are known as bastardy bonds. There was usually a guarantor required to countersign the bond who would become liable if the father defaulted or ran off. This person was often a relative with money or assets behind them or it may have been the father’s employer.

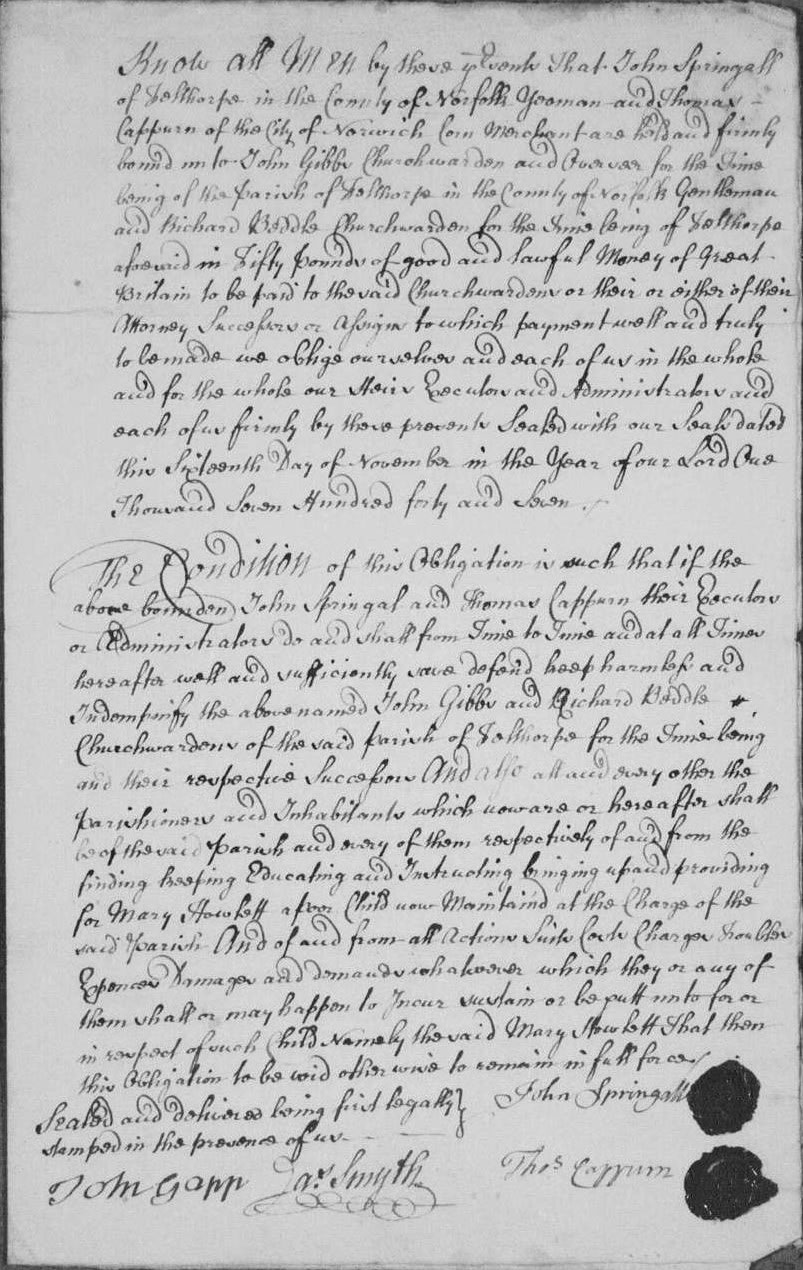

Our example of a Bastardy bond is from the Parish of Felthorpe in Norfolk recorded on the 16th November 1747 where the parish officials were concerned about obtaining maintenance for a “poor child” identified as Mary Howlett. In the record the Churchwardens were binding John Springall of Felthorpe, who presumably would be the father, and also his guarantor Thomas Cappurn, a corn merchant from Norwich.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

Bastardy warrants

In the case of a man who denied to the officials that they were the father of the illegitimate child, and refused to sign a bastardy bond, then the overseers of the poor could go back to the local magistrate and apply for a bastardy warrant. Once the J.P. had issued the warrant the local constables were then able to apprehend the alleged father and bring him up before the magistrate, or he may be required to provide sufficient surety that he would appear at the next quarter sessions court when it sat. If the alleged father had not the means to provide sufficient surety then he could be incarcerated in the prison until the court sat. Bastardy warrants were also issued in the case of an errant father absconding, or not making the maintenance payments that he had agreed to.

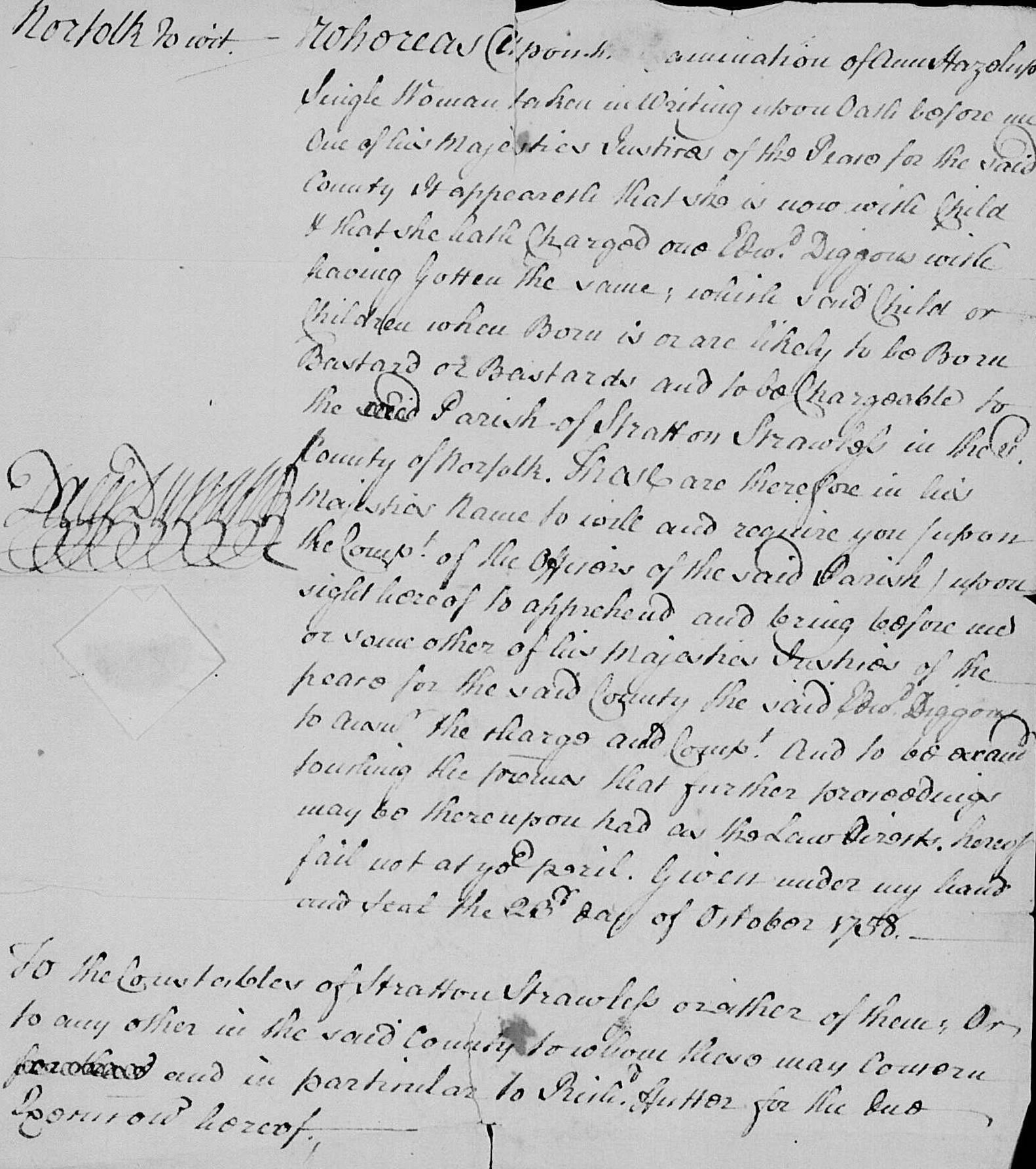

In our example, from the Parish of Stratton Strawless in the year 1758, we see that the J.P. has issued a warrant requiring the officers of the parish to apprehend and bring before him, or some other of His Majesty’s Justices of the Peace for the County, Edward Diggons who allegedly was the father of Ann Hazell’s child.

Bastardy orders

These legal decrees were issued by the justice of the peace when a man was ordered to pay the overseers of the poor and churchwardens a weekly maintenance for the child. The putative father will have appeared before the J.P. and given the chance to admit paternity of the child and marry the mother or sign a bastardy bond. Some, however, will have denied being the father of the child. Unless they could prove that they were unable to have been the father for good reasons, such as having been abroad or in prison at the time, then the justice of the peace would issue a bastardy order. If the man still denies being the father then his recourse was to appeal to the quarter sessions court. This, however, came with the threat of being liable for costs if the case went against him. The proof that was needed to overturn a bastardy order was very difficult for the man to furnish the justices with.

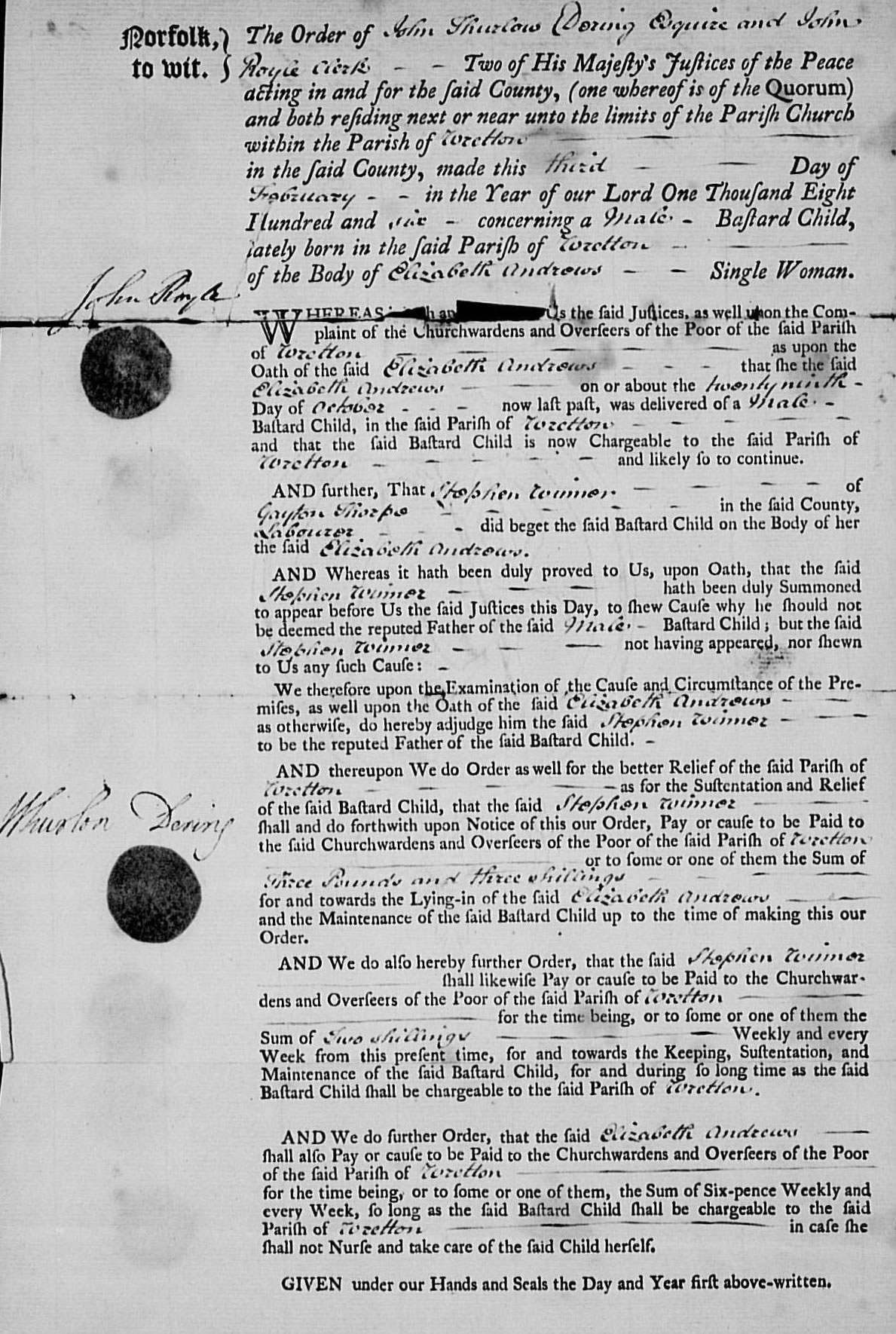

Above we see the maintenance order that the Justices have issued to compel a Stephen Winner to pay for the “Male Bastard Child” he had reputedly fathered with Elizabeth Andrews in the Parish of Wretton 29th October 1806.

Searching the records

To find a Bastardy record you will need to search for the mother or the father’s name as these records often did not name the child. They were intended to identify the parents in order to relieve the parish from the burden of paying maintenance for the baby.

Using the Advanced Search on TheGenealogist, select the Parish Record Transcripts and choose Norfolk as the county. On the next screen enter the mother or the father’s names such as our next example of “Elizabeth Mountain”. At the bottom left of the search box select “Bastardy Record” from the Event Type. You can select a date and a range with plus or minus a number of years it is also possible to narrow down the area and the abode.

In most cases your research will have probably taken you back to a child’s mother and so, as in the example in the next image we have entered her name into the respective fields. Alternatively you can search for a father of an illegitimate child in the same way, which is particularly informative when discovering someone who has fathered more than one base born child!

Parish records are one of the most interesting sets of records for discovering our ancestors and sometimes can include much more than just baptisms, marriages and burials. These records from the various Parish Chests of Norfolk allow us to find out about a section of society that can sometimes be difficult to trace back: those of illegitimate birth.