Jodie Whittaker is an actor who has made her name in some of Britain’s best loved dramas including playing Beth Latimer in Broadchurch. She came to prominence in her 2006 feature film debut Venus, for which she received British Independent Film Award and Satellite Award nominations. It is for her latest role as the Doctor in BBC1’s Doctor Who that she is now so well recognised.

Jodie has said how she has always been fascinated by her family history. She was brought up in a small family with little opportunity to ask about the details of her past family, so her knowledge is limited to various bits of “hearsay”. One family member that Jodie had a particular strong love and connection to was her paternal grandmother, Greta, who died in 1998. Jodie says, in her episode of Who Do You Think You Are? in the 17th series that is broadcasted by BBC1 on 12 October 2020:

She was like a movie star to me. And she had the coolest name. She’s called Greta Verdun

On her maternal line, Jodie knows about a mining connection and thinks that her great-grandfather and his brothers may have worked through a strike at some time in the 1920s.

There’s so much we don’t know. And I really would love to find out

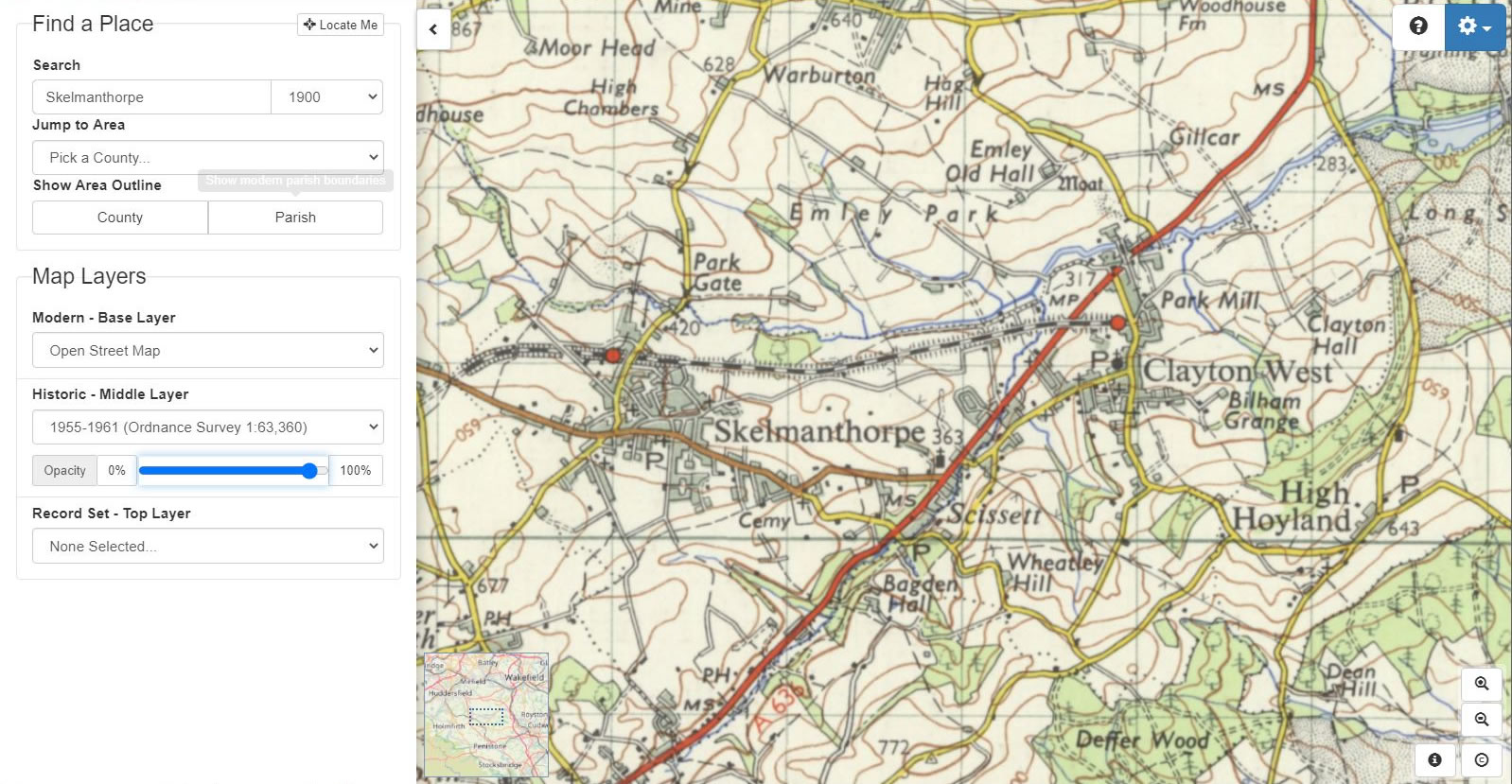

To begin her family history journey Jodie travels to Skelmanthorpe in West Yorkshire, which is the village where she grew up to meet up with parents, Yvonne and Adrian, who still live there today. On the way there she reveals to the viewers that in the area she is not known as the TV actress, but rather as her father’s daughter.

So Skelmanthorpe has got a really lovely nickname called Shat. Round here I don’t get: ‘Oh, you’re that girl from the TV, aren’t you?’ I get: ‘Are you Adrian Whittaker’s daughter? Are you that Shat lass? Are you from Shat?’

Viewers of the top genealogy programme see Jodie meet up with her mum and dad at the Junction Pub, which was where Adrian grew up. Jodie’s grandparents, Harry and Greta, were landlord and landlady from 1951. At the time the Junction was a hub of the local mining community, with the gates of the local pit located at the back.

The three of them look at a photograph of Jodie’s grandparents at the height of Greta and Harry’s time running the Junction. Yvonne, Jodie’s mum, comments that her mother-in-law was born to be a landlady, and that she loved company. Jodie then recalls that Greta would always have a full face of makeup, no matter the time of day.

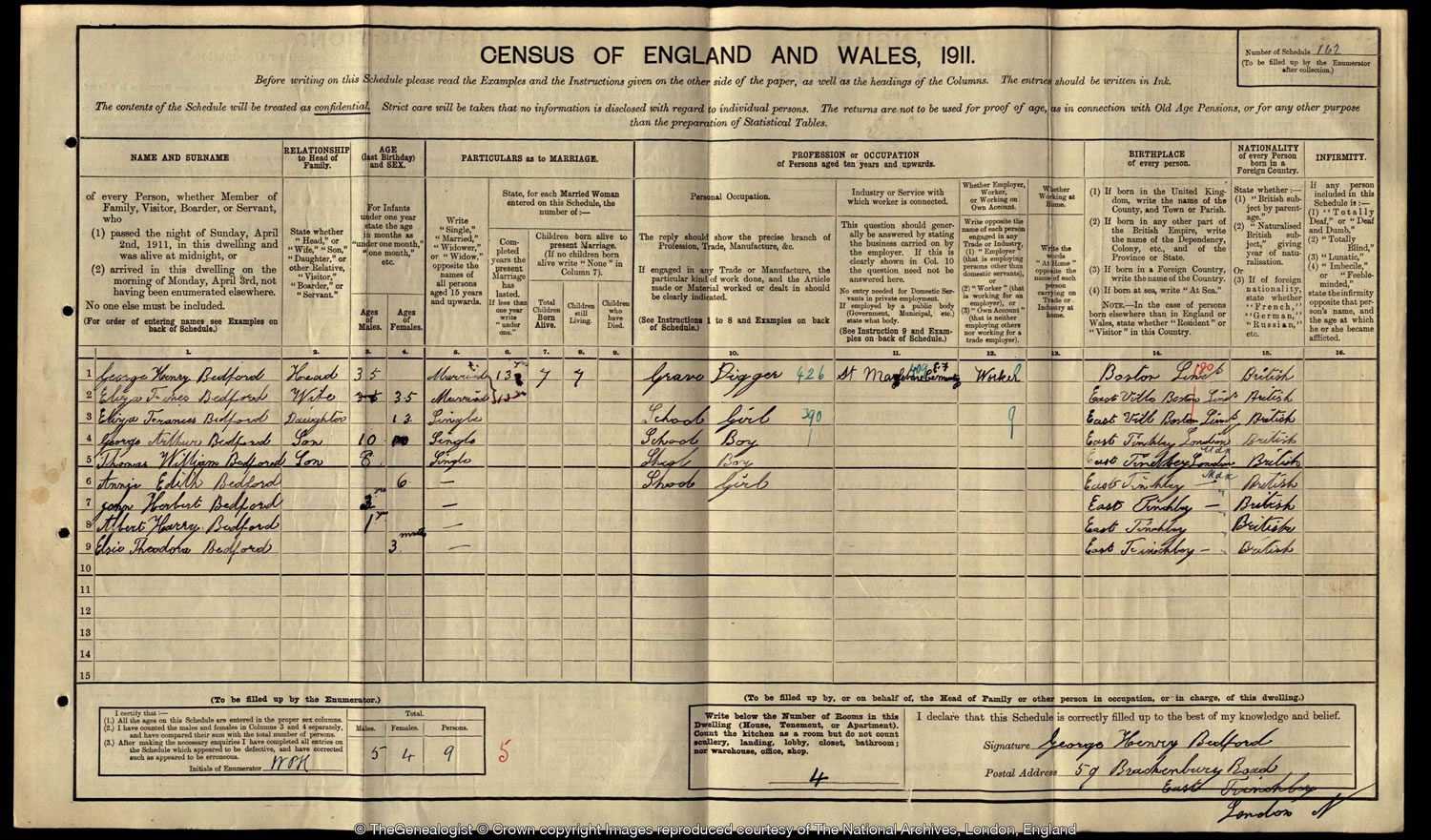

Greta Whittaker, neé Bedford, was originally from the Finchley area of London. She met Harry during the Second World War and we can find their marriage on TheGenealogist in Staincross, Yorkshire West Riding in the first quarter of 1949. Adrian explains to Jodie on camera that he thinks Greta’s middle name, Verdun, was a tribute to an elder brother who was killed at the Battle of Verdun in the First World War.

Jodie’s father had brought a folder with him which contained papers that they had found when his mother had died. One of the documents was a note written by Adrian’s mother which identifies her parents, Jodie’s great grandparents, as George Henry Bedford and Elizabeth Frances Clements. The note also mentions that Elizabeth’s eldest son, Walter Clements, had been killed in the First World War.

Jodie searches the 1911 census online to find out more details about her great grandparents. She discovers that George was a grave digger at St Marylebone Cemetery in East Finchley (London), and Eliza (or Elizabeth) was from Eastville in Lincolnshire. Jodie is confused by the census as there is someone missing, Walter he was not living with them.

I think there’s something potentially quite interesting that’s gonna be found out in Eastville. Oh, my mind’s whirling now

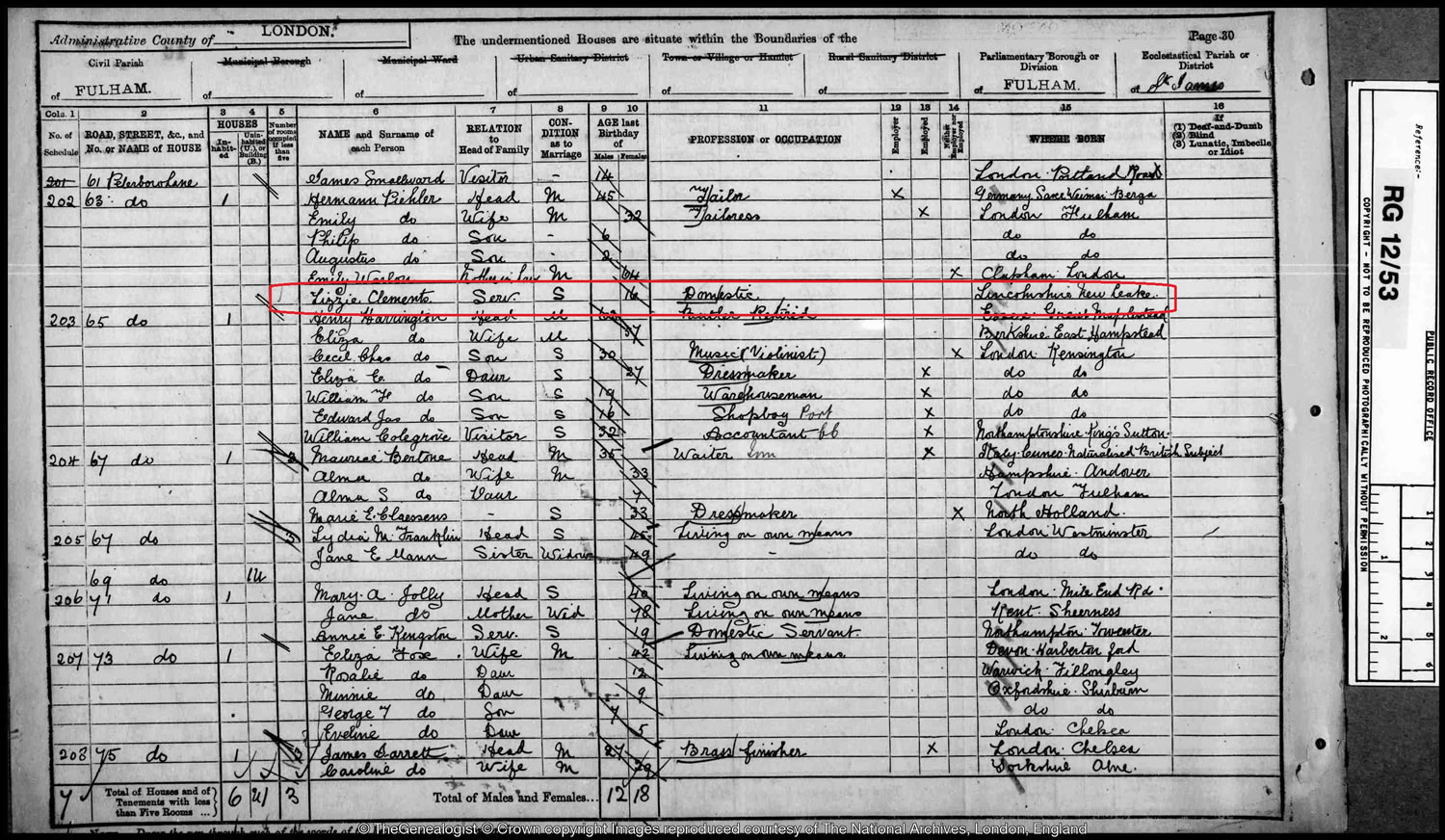

Next stop for Jodie was Eastville, Lincolnshire, where she met up with a social historian Dr Laura Harrison. Consulting the 1881 census for Eastville Jodie finds her great grandmother Eliza, aged five, living with her mother Sophia (Jodie’s great-great grandmother). Then they look at the 1891 census for Fulham in London, where Eliza was working as a domestic servant at the age of sixteen.

Jodie realises that her great grandmother would have conceived Walter at around this time. She wonders about who the father had been and is concerned that somebody may have taken advantage of the young Eliza. The next copy of a document that she is shown is the 1893 birth certificate for John Walter, son of Eliza Clements. It is from Lincolnshire and by the lack of a father’s name indicates that John Walter Clements had been illegitimate. Dr Harrison explains that John, or Walter as he came to be known, probably never knew the identity of his father.

So she’s come back to Lincolnshire, to Boston, presumably come home. She’s…had to do that…journey at 18, morning sick, and absolutely terrified

Jodie learns that four years later Eliza married George Bedford in 1897. Together Eliza and George would have eight children. By the time of the 1901 census the couple had moved to live in East Finchley while Walter lived far away from his mother and half-siblings up in Lincolnshire where he appears with his grandparents, Thomas and Sophia Smith.

See, I kind of suspected little things like this, but … I don’t know, it’s just that idea of a little kid being left and, you know. Yeah, that’s just… heartbreaking

An article in a newspaper from October 1914 that Jodie is shown in the TV programme reveals that Walter, now aged 21, travelled from Lincolnshire to Southampton in order to volunteer with the Red Cross at Netley Hospital on the banks of the Solent. It is the start of the First World War and this was a large military hospital which received wounded soldiers returning from the Western Front. During the four years of the war, Netley treated some 50,000 patients. Notwithstanding that he saw the injured soldiers returning to Netley Walter still decided to join up and ended up serving in France himself, where he would ultimately lose his life. Jodie is distressed by the thought.

It’s … of heartbreaking to think that this 21 year old who’s starting probably the first major adventure of his life…it is the last, and that he isn’t gonna make it to 30.

Following in the footsteps of her great uncle Walter, Jodie travels from Lincolnshire to the site of Netley Hospital on the Hampshire coast. The TV programme arranged for her to meet writer Philip Hoare and together they saw the remnants of the railway line which brought wounded soldiers by ambulance train from Southampton Docks. While nothing but the chapel remains, Philip explains that the main hospital building had been a quarter of a mile long, the largest brick building of its time. We can find an earlier image of it within The Navy and Army Illustrated, March 4, 1898 edition from the Newspaper and Magazine collection on TheGenealogist.

Access Over a Billion Records

Try a four-month Diamond subscription and we’ll apply a lifetime discount making it just £44.95 (standard price £64.95). You’ll gain access to all of our exclusive record collections and unique search tools (Along with Censuses, BMDs, Wills and more), providing you with the best resources online to discover your family history story.

We’ll also give you a free 12-month subscription to Discover Your Ancestors online magazine (worth £24.99), so you can read more great Family History research articles like this!

Jodie is told how, as an orderly at Netley, Walter would have been trained in anatomy and first aid. He would have worked on the frontline caring for the newly arriving casualties who would have come off the trains still caked in the mud and blood of the trenches. In late 1915, after a year at Netley treating the wounded, and seeing what war did to humans first-hand, Walter enlisted to fight in France himself joining the King’s Royal Hussars.

It’s so weird because the only connection I have to this person is my Grandma Greta, and I was really, really close to her. But this person is now completely alive in my mind and is a living, breathing soul

He will have seen death on a daily basis. And I don’t think in seeing that you have the naivety to think you’ll be okay. So in a way he’s doing it probably knowing he ain’t gonna come back

I’ve never had to do something that…the inevitability would be death. Bricking it but doing it! That’s a hero to me.

Jodie visits the archives of the regiment in Winchester to discover more about Walter’s service in the First World War. Here she learns, from military historian Dr David Kenyon, that he was one of 20,000 British soldiers who rode on horseback as a member of the 10th Hussars cavalry regiment. Jodie is shown the 1908 pattern cavalry sword which they would have carried and is given a gruesome explanation of how the mounted troops used it to kill their enemy. The sheer weight of the weapon brings home the brutality of the conflict.

Wanting to find out more about the family story regarding her grandmother’s middle name, Verdun, and the tale that this name was chosen to honour the memory of Walter, who died at the Battle of Verdun around the time of Greta’s birth. Unfortunately this story, as Dr Kenyon reveals to Jodie, cannot be true because Verdun was fought by the French Army and no British forces were involved in the battle. The explanation is that at the time it was fashionable to name a child after a contemporary battle. Eliza and George were simply following the trend of the time.

So this bestowed, grief-ridden name is not so. It’s more of a: ‘this is a place I’ve heard of!’

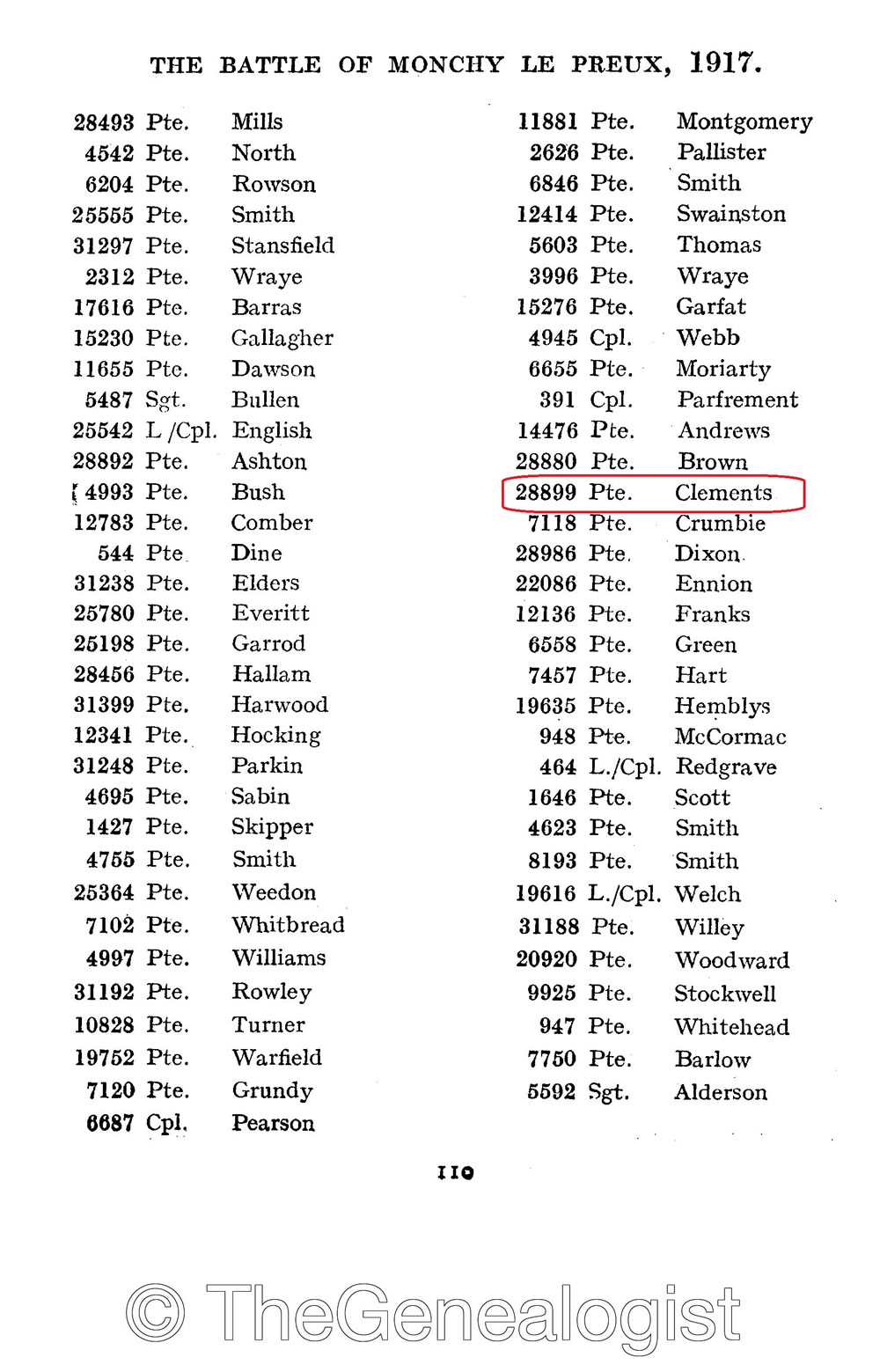

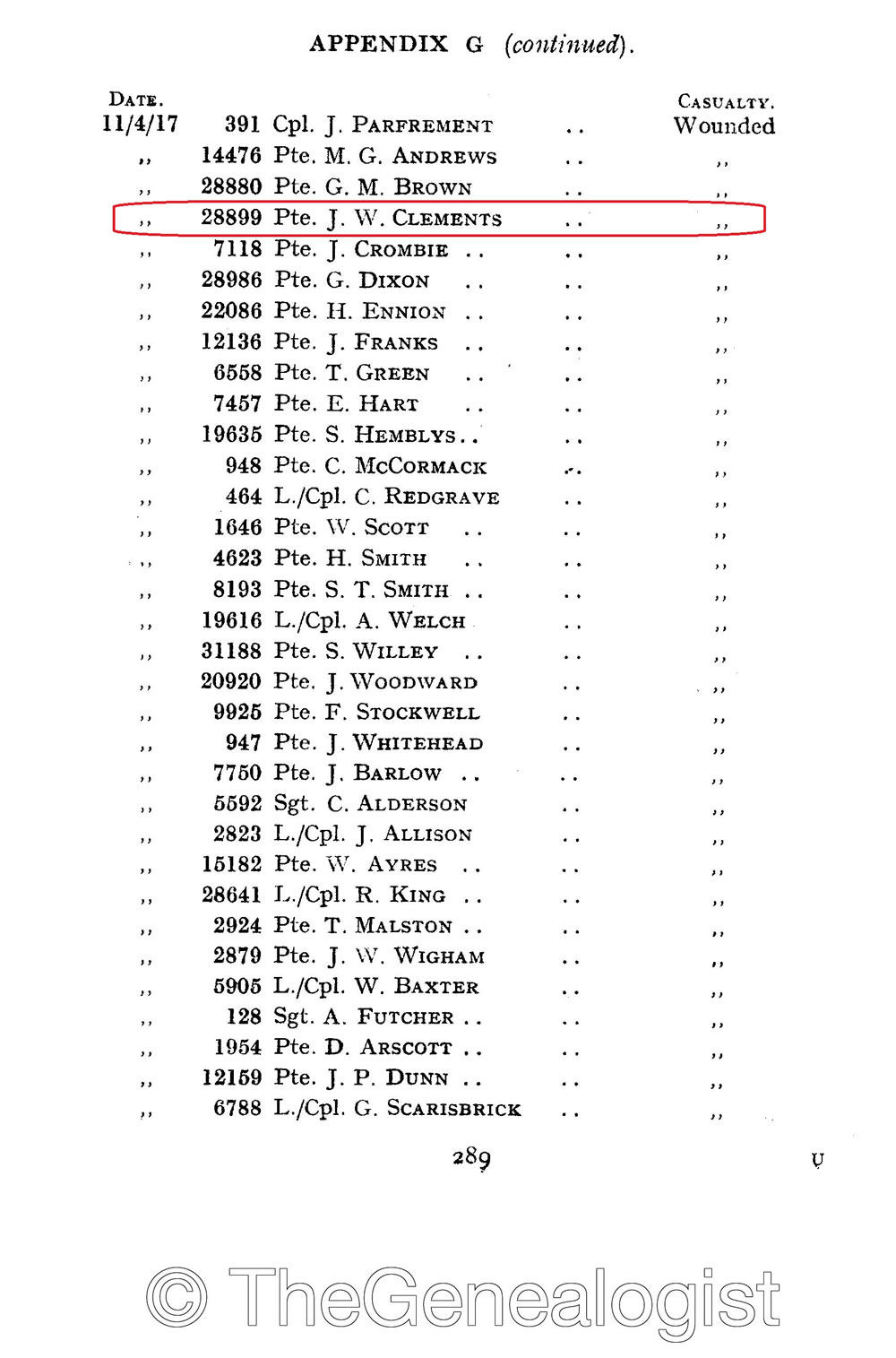

Having discovered that Walter did not die in the Battle of Verdun, Jodie next learns that Walter was involved in a significant battle during the spring of 1917. She reads an account written by a fellow member of the 10th Hussars describing the heavy casualties that they suffered at Monchy Le Preux. Jodie then consults a document which lists those who were killed and wounded. She is relieved to find Private Clements amongst the wounded, and learns that he was evacuated back to England.

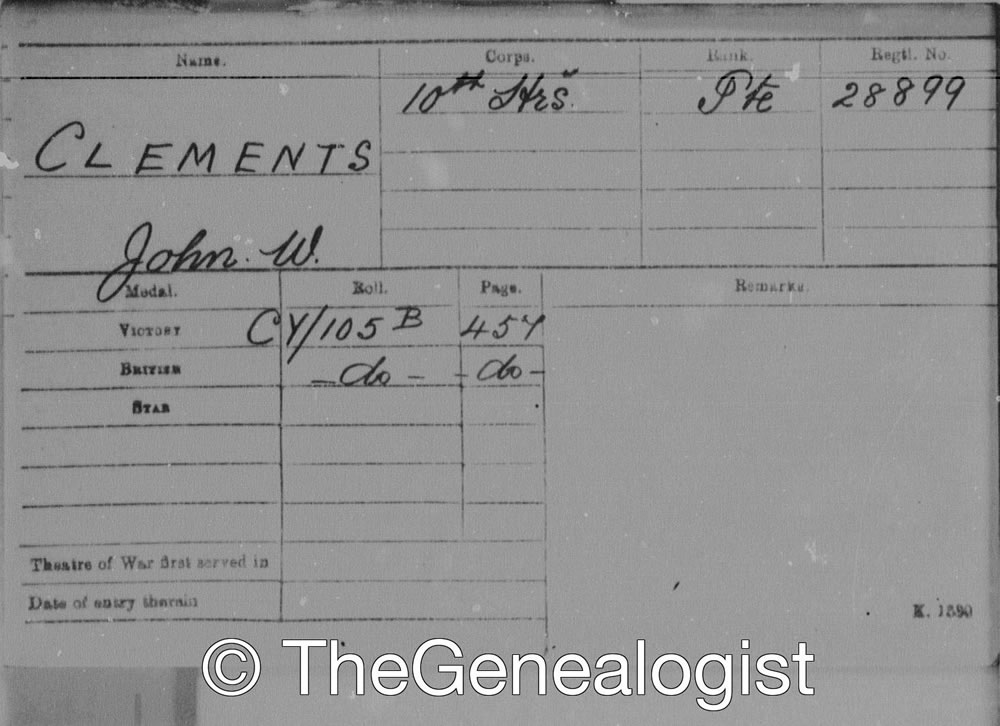

On TheGenealogist, within the extensive military records, we can find Private Clements listed in the Regimental Records & Histories, firstly on the page for the Battle of Monchy Le Preux. He appears again in Appendix G that gives us the date (11/4/17) when he was wounded.

Jodie appears to find the information that Walter was still alive and serving in France well after the birth of his youngest half sister, Greta, somewhat flummoxing.

The relationship between Walter and his mum… it’s much more disconnected than I thought, that bond. I thought it was intense – so much so that she named her youngest child after him. But in that being not the case, that leaves it all a bit adrift. I really hope to be able to find out something that connects them and there’s letters of comfort, there’s contact, there’s something.

Jodie gets to speak to the medical historian Dr Emily Mayhew in the programme. The expert is able to tell Jodie more about Walter’s injury, and then shed some light on what happened next in his story. Walter had suffered a thigh wound, but he recovered following treatment in England and then returned to his unit in France to fight. Jodie asks whether Walter would have been required to go back to the Front. Emily clarifies that this would have been his decision.

Wow! See, all this is making me just think… he just feels like a lonely soul to me. It doesn’t feel like he has got his mum and his eight siblings around his bed begging [him] to stay

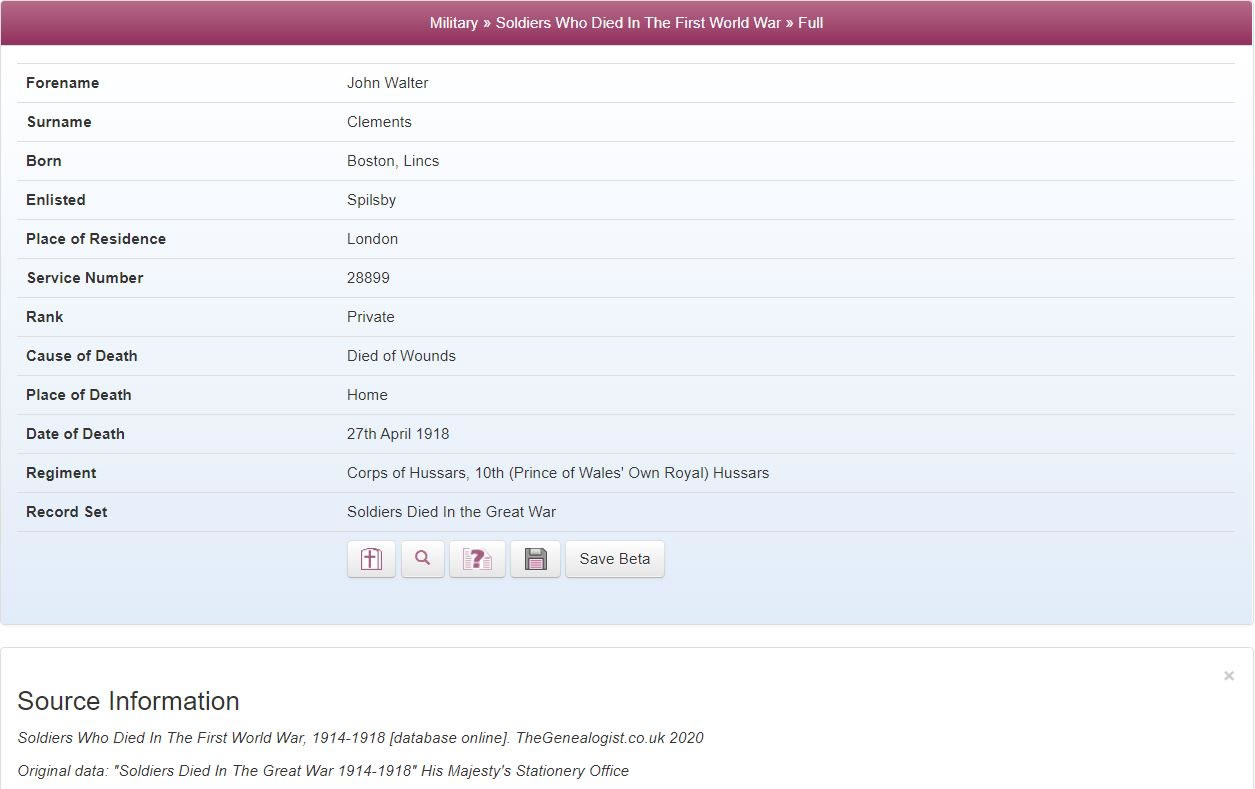

Jodie finds out that this was not the only time he was a casualty. Following his return to the fight, Walter was wounded once again in April 1918. However, this time his injuries were far more severe to the extent that he would not recover. Jodie reads a document which explains that Walter died on 27th April 1918 from injuries sustained from a shell wound to the back. She reflects on his young age, just 24 years old, and hopes that he was not alone at the time of his death.

Jodie is seen consulting the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website to find out where Walter was buried. What is a surprise to Jodie is that Walter’s grave is located in East Finchley Cemetery and this, of course, was where her great grandparents Eliza and George, Walter’s mother and stepfather, lived with their children. Earlier, Jodie had discovered that this had been the cemetery where George worked as a gravedigger; she sees a welcome connection.

It feels like there’s been an involvement here from Eliza; that she knew he was in that hospital and that then she got to bring him back to her home. And for the rest of her life… oh God, so upsetting…she has her nine children around her. And for those other children they’ve got this place to come to and to celebrate someone’s little life. I’m slightly feeling like…a bit desperate to go because I really, really want to visit the grave

Jodie arrives at East Finchley Cemetery where she finds the distinctive limestone memorial of a First World War grave. The inscription reads “10th Royal Hussars, Lance Corporal J. W. Clements”.

To have this here, it feels like the family is connected. There’s no doubt in my mind that Eliza and George and those children had stood around this

Jodie’s Maternal Line

The family history show then takes us with Jodie back to Yorkshire to find out more about her maternal great grandfather, Edwin Auckland. There is a photograph of Edwin and his four brothers surrounded by police officers at the time of the 1921 miners’ strike that sparks the hunt. Jodie believes that they ran the New Inn Colliery in Clayton West, and that controversially they worked through the 1921 strike.

Access Over a Billion Records

Subscribe to our newsletter, filled with more captivating articles, expert tips, and special offers.

I’ve always had this photograph, I got it off my Mum years ago and I’ve had it on the wall with this story built around it that I’ve probably embellished certain little strands of it. It’s not an ideal bit of your family history. So it would be nice to find out that it’s not as bad as I think

Jodie meets Yvonne, her mum, so that they can talk about the Auckland brothers. The two of them look at the photograph together and Yvonne confirms that the police were present to guard the Colliery gate so that the brothers could get in and out of the pit without coming to harm. Jodie is not impressed and refers to her ancestors as being “scabs”, workers who cross a picket line to work during a strike. Her mother agrees with her daughter and tells Jodie that when she was at school in 1961, some forty years later, children would say “you’re an Auckland; we’re not allowed to talk to you”. Yvonne says firmly that she has never defended the members of her past family for their actions.

Living here during the ‘80s, like the idea that you work through a strike is just … it feels like it goes against everything you’re kind of brought up to believe in

Mother and daughter discuss that the Auckland brothers had been fairly wealthy. They all lived in large houses and their children went to private schools. Jodie is keen to find out how they came to be successful. She looks at the marriage certificate for Edwin Auckland and notices that his father, Jodie’s great great grandfather, who was also named Edwin Auckland, had been listed on the document as a “gentleman”. Jodie says to her mother:

What is random to me is that someone not that far gone were called gentleman…and then … and then there’s us!

I really wanna know about Edwin Auckland Senior, the gentleman. Because with that comes the information of why these brothers have got a mine

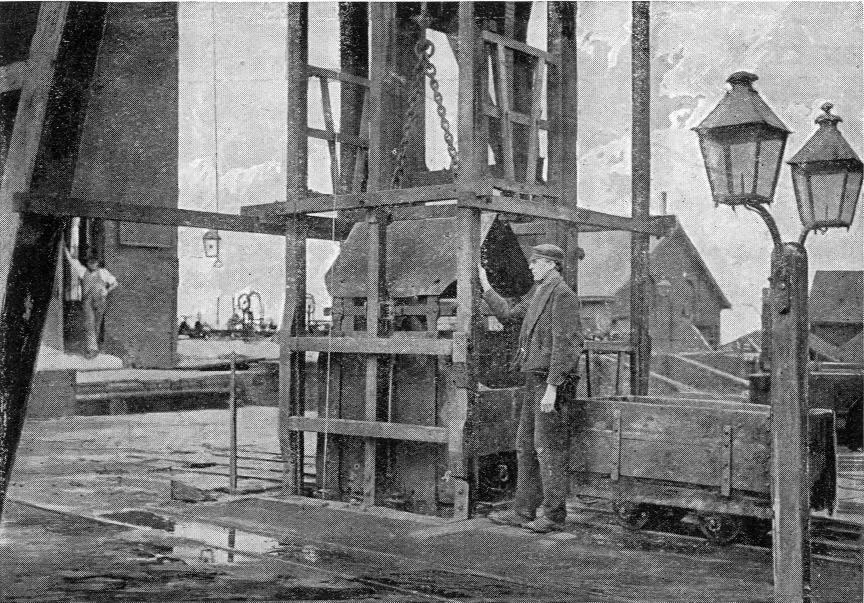

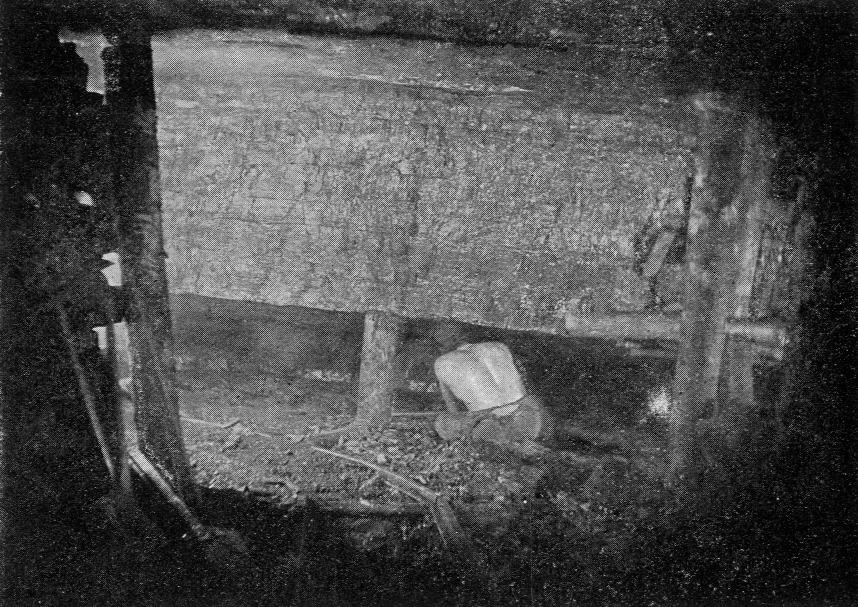

In a desire to see if she can find out more, Jodie and the cameras pay a visit to the National Coalmine Museum near Wakefield. Here she meets an ex-miner, Pete Wordsworth, for a tour of a coal mine. She is also shown the obituary of Edwin Auckland Senior which reveals a shocking fact about his early life. It turns out that he began working in the pit at the age of eight where, like other young boys, he endured brutal and illegal working conditions. But this was not where he stayed as he gradually climbed the ranks in coal mining to become a contractor, which meant he would employ other men, including his own sons.

The Aucklands continued mining during the First World War when they became essential workers and so did not need to join the military. After the conflict, in 1921, the Aucklands were able to purchase their own piece of land and this became the New Inn Colliery. Jodie is amused to discover that the fields on which she played as a child lay over the workings where her great grandfather had once mined. She had never realised the connection to her family history lying below her feet as she had had childhood fun on the surface.

Jodie goes next to the National Union of Mineworkers and meets Professor Keith Gildart to find out more about the events of the 1921 miners strike. The academic explains that with the end of the war, coal prices slumped and colliery owners cut miners’ wages by a third. The majority of the country’s 1.2 million miners refused to accept this reduction in their pay, so the owners locked the miners out of the collieries. Just a few mines continued to operate including the one run by the Auckland brothers. As demand for their coal was high they saw lucrative profits in return. The Professor explains that the miners’ strike ended in their defeat when they were effectively starved back to work.

History repeated itself during the general strike of 1926. This time 3 million industrial workers downed tools in solidarity with the mine workers who were being compelled to work longer hours for less pay. Yet again, the Auckland brothers had kept their mine open throughout the dispute. The strike, however, did not end well for the workers who once again had to go back to work having not achieved an improvement in their wages or hours. While the miners were getting less the Auckland brothers prospered. Jodie is told that the combined value of brothers’ estates would have been, in today’s money, approximately £7 million. Though celebrating that her great grandfather was able to rise from slogging underground as a child, to enabling his family to become wealthy, she is disturbed by the plight of those not so lucky.

Oh my God! I mean I was aware that the Auckland brothers were comfortable, but I didn’t really realise it was much more than comfort…

So there’s a way of looking at this that is just filled with pride, because a man bettered himself and then his entire family, and that family took on that work ethic of grafting and took it to another level. But the problem is…it’s when it comes at a cost. On your doorstep there must have been enough families that… that you saw who sacrificed so much just to try and have their basic rights.

I think it’s just where you lean emotionally, and I lean that way!

Sources:

Press Information from Multitude Media on behalf of the programme makers Wall to Wall Media Ltd

Extra research and record images from TheGenealogist.co.uk

BBC/Wall to Wall Ltd Images

Wikipedia Commons